A Russian Journal: In the Mood for Discovery, 1991

Thirty years ago, in the fall of 1991, I traveled to Russia for the first (and so far only) time. It was something of a personal journey, but I did end up writing a couple of stories for The Kansas City Star. This was in the midst of the momentous pivot of history following that summer’s failed military putsch. Mikhail Gorbachev was on the verge of resigning and Boris Yeltsin was securing leadership of a new Russia as the old Soviet Union began to dissolve. In fact, I was there for the last days of Leningrad, leaving for points south on the day before the historic city reverted back to St. Petersburg.

Part of my interest stemmed from knowing little of the Russian blood that coursed through my veins. (Some time later, I’ll write about that, too.) Two decades earlier, after the first day of a Russian language class in college, my teacher, a Russian immigrant via France, came up to me and said, “You are Russian.” Well, yes I am. And after two years of college Russian, and an accent that sounded natural, I knew just enough to be dangerous. I could start a conversation, then I’d have to bail out rather quickly. Still, there were a few times on the street or in the subway where my reading skill was good enough to lead some of my fellow travelers around. I thought I might stick with the language and even brought back a little book of Mayakovsky poems in Russian that I figured I would translate some day. Best laid plans—just another one of those possible projects that fell by the wayside.

But for this journey, I had signed up for a group tour whose purpose was to foster cultural dialogue among writers and artists from East and West. The umbrella organization was known at the time as the Citizen Exchange Council.

What I’m leading up to here is this. Not long ago, I tripped across my old files of notes from that journey. It occurred to me that, given the ongoing power posturing between the U.S. and Russia and the disturbing nature of Russia’s autocracy today, my old notes might contain some insight or evidence or merely just some entertainment for understanding aspects of life in that vast nation.

I’ve begun to clean the notes up a bit, zapping some of old coding and typographical hiccups, and will start presenting the raw files here. There’s often a kind of shorthand, raw material quality to some of this. Again, perhaps it’s another missed opportunity—could all this be refashioned into something larger or meaningful. I don’t know.

The first entry below covers the first three days or so of the two-week excursion. The second section below, “At the Writers Union,” contains a roundtable discussion our group engaged in with writers in Leningrad, who were in the midst of re-orienting their lives as the state publishing apparatus disappeared and poets and novelists were left largely to fend for themselves. Subsequent entries included similar transcribed roundtable conversations with media people, journalists, and others.

I’ve also begun to scan some of my extant photos, though I remember with regret how a local (Kansas City) film processor botched and ruined a large batch of my negatives.

First Impressions

Nov. 1-2, 1991

Much empty time today. A close call at the KC airport then a delayed takeoff.

At Kennedy International Airport, much milling about and meeting my fellow tourists as we wait for our flight to Helsinki and beyond. I have a beer with a fellow from Zurich visiting in the states, on his way to Florida, and lend him a couple of Sudafed, because he's complaining of headache and sinus problems, although his English is not too good and I may be projecting my own flying problems onto him. He's a mechanical engineer of some kind, would like to stay in the states but he doesn't know how, it sounds like.

In a briefing, tour organizer Harlow Robinson is very optimistic. He says perceptions break down on generational lines; people in their 40s and 50s may be more desperate, younger people are more optimistic about the future.

New York to Helsinki is to be a seven and a half hour flight. The DC-10 is crowded, cramped, although I'm lucky to have an empty seat next to me. (We figure out later it must have belonged to June Turner, one of our CEC fellow travelers, who, upon leaving California picked up her son's passport rather than her own and will be delayed a day while it's overnighted to her in New York.) I read Russian history, and a little Graham Greene (Travels With My Aunt). Dinner was filling and someone shares with me their smoked salmon. I save the foil-wrapped Bel Paese cheese for later, but drink two small but generous bottles of white French wine. I manage to doze a bit, sneak a smoke in someone else's seat in back, and ignore the movie—John Candy in “Only the Lonely.” Finnair seems quite efficient. The Nordic attendants look as if they won't take any guff. They have just passed out water and orange juice. I can't help but anticipate what’s to come, but I hope I won’t be too sleep-deprived to appreciate it.

There are two ways of looking at the turmoil in Russia. One as a society in chaos, which it is, but hopelessly inept and doomed. The other is more optimistic—great opportunity, anything can happen, and the people are making their own way after so many years under the iron fist. It will take some time, years probably, for the bubble to find plumb, but now there is great excitement amid the limitless ocean of possibility in which the Russians are now swimming.

At the St. Petersburg airport—although technically, for a few more days, the city was still Leningrad—the flotilla of tired Aeroflot jets that we see upon landing makes you wonder if they're real or just phantoms, props.

Leningrad arrival: A welcoming brass band launches into “In the Mood.”

A brass band plays as we wait to board our Intourist bus. Five horns and a snare drum; ditties for dollars and cigarettes: “America,” “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” It's sunny and cold. They dive into Glenn Miller's “In the Mood,” and Margarita, our Intourist guide, says “Look, Glenn Miller, don’t give them any more money.”

“I've never seen so many meetings in my lifetime as your group has,” she says. Sometimes she says Leningrad, sometimes St. Petersburg, often catches herself midway through. “Yes, there is a lack of petrol”— there’s a double line at a station we pass—“you've read about it, so don't be surprised.” We pass a memorial to the Siege of Leningrad at Victory Square; a line at a dairy story—Moloko, the sign says, milk; dingy industrial district.

The Pribaltiskaya Hotel sits on Finland Bay. It’s a rather swank but cold-looking place with a dark but bustling polyglot lobby and better-than-expected spartan rooms. Pivo, a Heineken, tastes good in the chrome, black and purple express bar, only $2 a can. Lunch at the hotel was as odd as expected. A small plate with a slice of salami on top of a cabbage salad. Someone said it’s not smart to eat salads. At one table, one of two for our group, I dished out our nine bowls of soup, a chicken and corn-meal tasting concoction, bland and smooth. A plate of chopped beets piled high and topped with something creamy was passed around. Then we were served something like a chicken-fried steak with mashed potatoes and chopped scallions. Glasses of odd-tasting carbonated lemonade were on the table. Later came coffee—very black—tea, and a dish of vanilla ice cream. This afternoon we did more bus-touring. I took pictures, bought a military medallion, or something of the sort, off a grungy kid for a dollar. Nodded off occasionally on the bus. A short nap did wonders. Wandered around the hotel before dinner. The unexpected sight: a dozen American style slot machines and video-poker games lined the wall and a handful of men played them with abandon. A pale imitation of Vegas but a captivating sign of democracy all the same.

“You don't have to leave the country for good anymore,” Harlow says.

Sunday's sked: 2 p.m. Leningrad Writer's Union; 6:45, Maly Ballet: “Esmeralda”; Monday afternoon: free; 8:30 p.m. art galleries; Tue, 10 a.m.: Hermitage; 2:30 p.m. Dostoevsky tour, dinner at 7 early departure Wednesday, bags picked up at 5, leave at 5:30 a.m.

There are two Russias: tourist Russia and the real thing. So far, all I've really seen is the former, although when I gave a dollar bill to a forlorn boy showing me a military-style pin in his hand, black with grime, I felt I came close to the latter, even if I was Americanski and he made his way with tourist scams. When I asked if he’d consider some rubles, he was adamant. “One dollar,” he said sternly, almost shouting.

The public areas of the Pribaltiskaya Hotel are teeming with tourists and unabashed hustlers and apparently shady folks of all types. You quickly learn the language of this gray world. “Would you like military coat. They're very popular,” one blond-haired merchant offered as a few of us sat having beers in a mezzanine lounge. And every long-legged, dolled-up woman is sized up for what she likely is—for what she may or may not be. I hear that free-spending, hard-drinking Finnish businessmen are the sex workers’ most lucrative customers.

Long talk over beers with Harlow Robinson and David D'Arcy about everything: the changes here, free-lance journalism, American culture, Finnish and Russian movies, all the things and people we see around us and are here to discover for ourselves. Now I need sleep, finally, after nearly two days without it (more like a day and a half considering the time change). By morning I expect to be refreshed and ready.

Rostral Column with Neptune statue, St. Petersburg.

Please, please me: Pozhalista is a wonderful word. Not only does it mean “please,” but it also means “you’re welcome,” so a conversation, or transaction begins and ends with it. Kohfe, pozhalista. Spasseebah. Pozhalista.

I wake up after barely an hour, unable to go back to sleep. My mind is racing, trying to think in Russian words. My mouth is dry—the wine at dinner, the beer, the cigarettes?—and I have this horrible thought: I spent $14 in hard currency today without getting any receipts!

A cashier at the hotel was kind enough to change some dollars for a couple of us this afternoon. A woman ahead of me got 350 rubles for $10, I got 150 for $5. Go figure. The cashier was a little exasperated—I suppose she was breaking the law, but only in a small way, but to the next person who asked she said, “You must go to the exchange desk.”

So now I'm awake, it’s 1:30 a.m. I know the beer bar is open till 4, but I think I’ll stay here and read Chekhov instead.

Nov. 3

A late start. Stopping at St. Nicholas Cathedral, with its gold domes and baroque forms and blue and white color scheme. In the time of Catherine the Great this shrine to a patron saint of seafarers was the main cathedral in all of the Russian empire. Many people milling about, old women lighting candles, group baptism under way, a funeral to come. Service upstairs with a choir; men women, and children here.

Church of the Savior of Spilled Blood (1863-1907)

St. Isaac’s Cathedral: there’s talk that it will soon be turned back to church; it has been a museum (of atheism? Wasn’t Kazan Cathedral, too?) since 1934. Red granite columns outside. Inside: malachite columns, two lapis lazuli columns at holy gate, a stained-glass Christ; icon stand includes St. Catherine and Alexander Nevsky, Mary, Christ, St. Isaac, St. Nicholas, three tiers of icons, gilt plaster statues, capitals, crenelation. We stand in the rotunda; cast-iron figures. It was a museum of atheism for a time (but also at Kazan Cathedral--am I confused about this, but did both serve that purpose?). The rotunda once had a Foucault's pendulum, but it was removed two years ago and now a dove has been restored to the dome at the top of chamber. Ten years just to build the foundation in the marsh—in the first half of the 19th century. Massive pilings; frescoes painted under supervision of Brulov. Colored marble bust of A. Montferrand, the French architect who designed a church that commemorates the victory over Napoleon. Montferrand died of pneumonia one month before the church was unveiled (in 1858): a man of many ironies.

St. Nicholas Cathedral, St. Petersburg

Mosaics have been made, painstakingly reproducing the 62 frescoes, which have been systematically removed for renovation or safe-keeping; incredibly detailed mosaics. Also a heroic cast-iron bust of Montferrand.

400,000 workers built the church, many died while gold-plating the metal bases of columns, victims of the mercury plating process that poisoned them as they worked.

On the bus: Mayor Sobchak's first promise was to improve the roads, which badly need it. Margarita says, Leningraders will hold him to it, will toss him out of office he doesn't come through. Margarita says her favorite book is Gone With the Wind; she said that Russians swooned a year or so ago when the movie hit the screens here.

I spot on a news rack in the hotel lobby a recent (August?) issue of Foreign Literature (Russian translations). It has selections from Amy Lowell, Nancy Reagan (My Turn, I presume from the Russian title), and Henry Miller. I also pick up a thin newsprint journal, of sorts, that apparently is a short story by Agatha Christie. (I will hear over and over again the ascendancy of detective fiction and crime novels here.)

The hotel doorman turns away two Georgians who are trying to bring in a woman who apparently has no documentation. Margarita says, “There’s so much trouble and it happens so much with people from the South—Georgians and Azerbaijanis and Armenians. They have so much money.”

D’Arcy buys a black lamb’s wool hat from a peddler outside our bus for $9. (Thirty years later I still regret not buying a snow-white rabbit’s fur hat when given the opportunity.)

Thoughts on seeing the Maly Ballet’s “Esmeralda”: Classical ballet seems hopelessly stuck in the 19th century, in a way that no other art form can afford to be, especially one that takes up so much of an evening. I sit next to a couple from Ireland, whom I’ll run into again two days later at the Hermitage.

At the Writers Union

The Leningrad Writers organization is housed in a palace built for a Count Sheremetyev, an 18th-century nobleman, general and patron of the theater. We learn it was built not as a home but a place for receptions.

Maya Borisova, first a poet now a prose writer, talks about a previous exchange of delegates with Brooklynites.

Yakov Gordin, historian and prose writer, non-fiction, political; also independent publisher.

Mikhail Glinka, prose, looks like the silver-haired actor Leslie Nielsen; writes about Leningrad, independent publisher.

Alexander Zhitinsky, fantasy writer.

Leonid Semenov-Spassky, a doctor; worked in shipping; also writing prose.

Nevksy Times reporter Nadezhda Kozhevnikova, covering the meeting.

Alexander Bransky, translator; has done detective stories and science fiction, Robert Heinlein, George R.R. Martin, Raymond Chandler. (Later I meet with him for a short interview.)

Dmitri Karalis, science fiction writer and new publisher.

Modern art lines the walls, paintings, surreal, Kandinsky style, drawings, shades of Pollock. The writers are sitting at and around a table in the front of the room, and we all are sitting in chairs, auditorium style, facing them.

(Dialogue translated by Harlow Robinson.)

Gordin: “We would like someone to explain to us what the future will be. Since the union of writers has always been a state organization, the structure of the union will change according to changes in life. Maybe the union will disappear or will turn into a free association of writers. As much as other professions, many functions of union writers were ideological; when that function disappears ...

“The Leningrad union is different than others. Don’t know how it will change in the future.

“State approach to union of writers before was schizophrenic or ambiguous. On one side state tried to control the union, on the other hand, the state created an artificial greenhouse atmosphere for writers.

“To be a writer was a profession. In the west, writers get paid for what they have to contribute. State decided you will be a writer, even if you can't write, and if appointed and had any talent at all that would be wonderful. A member of the Writers Union did have guaranteed access to publication and of course there were writers who were favored by the government and those to whom the government was indifferent or hostile.

“Generally speaking, situation for writers here was actually pretty favorable. But that’s done. Now it’s over, and the average Soviet writer now finds himself faced with reality, facing a new world.”

Leningrad writers roundtable.

One member of our delegation asks whether the writers were looking for advice from us. Says Gordin: “Nobody can help us except us. All we can do is exchange our experiences. We’re not looking for advice.”

I ask whether all of these writers chose to be writers and do they plan to continue.

“We all plan to continue being writers.”

Glinka (related to the composer): The situation we lived under for so many years was very peculiar. The average person in the Soviet Union didn't really have any work to do. That meant we had a lot of people doing pseudo work, and that was true of our readership—we also had a pseudo readership. So we had a pseudo readership that gave birth to pseudo authors. And they fed off each other.

“And when it was always said with such pride that Russian people read more than everyone in the world, just because people on the subway or bus would read something in one hand while holding on with the other—but that was a very artificial kind of situation.” Borisova helps explain: “In a way it was an escape valve—a way for ourselves to think, we may not be very efficient, we may live badly, but we have a high level of culture and we read a lot. That was a way to rationalize it.”

Glinka: “We had libraries, schools libraries and others that could swallow up huge printings of books, any bad book, no matter how bad it might be, because the distributor was the state. So there were lots of readers whom nobody was reading but were very famous. Now the situation is changing rapidly. Now we’re seeing a real market for literature and books, although the emerging market situation still has a monstrous character to it. A niche for writers in our newly forming society has not been found. So we’re starting in the stone age.”

D'Arcy: “Do you have a better idea of who wants to read books, outside of subway riders who read bad books? And what opportunities do writers have to publish outside what had been state publishing houses?”

Glinka: “Here are two people. Two of the writers on the panel started small publishing houses, Text and Novy Helicon. Gordin (Novy Helicon) and Karalis (Text).”

Gordin: “I’ve also set up a small publishing house. A few months ago started publishing books on a commercial basis. So there are a lot of small publishing houses. And have to face incredible difficulties. The biggest problem for Soviet publishing houses is paper shortage. If you have money to buy paper you do, and if don't you don’t.”

Question: How choose writers?

Glinka: “The first book he did as a publisher, La Dame aux Camelias by Dumas (fils). And I hope you won’t be offended but on the cover we put a picture of a famous Western prostitute and it did very well. “

Karalis (Text): “We mainly publish science fiction and fantasy, but also Russian texts that have been published abroad but couldn't be published here; for example, (Vasily) Aksyonov (1932-2009) and other emigré writers. Our fantasy and science fiction writers do very well and they support some of the other things.

I interject that what everyone seems to be getting at is that there are books that are very popular, but not considered literature, the same dichotomy as in America.

Borisova: “Let me add one thing. You asked if we all were planning to continue writing. Of course, of course. Glinka has begun publishing but as of yet he has not published me or my colleagues here. The fact is that a great number of writers here—and not bad ones either—find themselves in a very difficult moral and financial situation. Let me just talk about myself. Most of my life I've written poems which were rather popular. I didn’t say whether they were good or bad, but they were popular. The books sold very well and very fast. Also I wrote a book of prose that sold very well and very fast. But the publishers who were publishing my books, especially my books of poetry, still insisted that they didn’t make money, that poetry didn't make money. The size of printing was never set by market reasons but by command from above. Same way prices were not set by demand but by command. It used to be you could buy a book of my poems for less than it would cost for a bottle of beer.”

Glinka: “That's the way it should have been. Poetry should be accessible.”

Borisova: “I also have written books for young readers. But it doesn’t mean the popularity of books in the past helps in the present. Publishers are not offering me any offers to publish. All of our important journals are losing subscribers. They’ve become very expensive and not a very important part of writing.

“We always thought that writers best to understand writing and the best help for writers should come from other writers. Through money or approval or just by reputation. Our Leningrad writers organization has started a charitable fund to help writers. I’m chairman of this fund. Young writers, poor writers, those who are just starting; older writers who have small pension and no other means of support; subsidize; we'll have a committee to decide who is deserving.

D’Arcy: “Again, how does a young writer getting started get published? And, if you were a publisher publishing for sheer greed what would you publish?”

Borisova: “I was a quite popular writer and I have a pension of 190 rubles a month”— about $6 on the day we talked, about $4 a couple of days later—“so you could call me a poor writer actually. I always wrote my whole life and was published my whole life.

Susan [name?]: “International PEN; one of missions to help writers who have no means of support? It's interesting that a writers union here would be working in the same direction.”

Glinka: “When our government is falling into ruins, I have ambivalent feelings. Of course, I'm very much oppressed...(turn tape over, some missed) so I can't help but taking pleasure in seeing old union of writers disintegrate, because its part of natural process that has to happen.”

Q: How many writers in union? 400 members in Leningrad.

Gordin: “I want to correct what I think is a slightly incorrect misconception. In fact nothing awful has happened. It’s not true that all writers who aren't being published now are in a hopeless position. I’m actually rather afraid of ‘social welfare’ for writers. Speaking about writers who used to be published a lot and made money and are not being published because of the whole change in the publishing structure, that’s the way it should be, and maybe he should not write anymore and go do something else. If we’re talking about old, sick people, then that's another matter. I basically agree with what Glinka said, but I still there are a lot of readers, millions of real readers. The real problem now is not that there isn’t demand for books. The problem is we have an outmoded, awkward clumsy system of distribution.

“I'm quite sure that within a reasonable period of time a real market situation will develop here and this difficult situation will pass. A real writer will always find his public.”

Susan: interested in magazines, literary quarterlies, have there been efforts to start new mags?

(Unidentified speaker): “Leningrad, a journal, went out of existence; outlawed by Stalin. Trying to start it again. but so far unable because of paper and other problems.”

Gordin: “Star, an old journal, last year printing of 300,000 copies, this year 50,000; price has doubled and it’s still losing money. What we've done to keep the journal afloat is to start other publishing enterprises. Price 50 kopeks a few years ago, now three rubles. I know in America when prices rise 3 percent or more it’s disaster but here prices are up 200, 500 percent.

“When it became really clear that the journal was losing lots of money, the first book we published to make money was The Handbook of Russian Home Remedies—published for 10 rubles. And we are also publishing a Swedish writer, Os. Lindgren: Pippi Longstocking: and now we’re doing an eight-volume set of Pushkin, you subscribe to the whole set: including his correspondence, and domestic things connected with Pushkin, archival material. We anticipate 100,000 people will buy this set. (Priced at 20 rubles per volume). All those books we published knowing they will make money.

“Of course it's a noble thing for a publishing house that finds itself in a difficult situation and to publish books.”

Question from me: “Would you publish Miss Borisova's poetry to make money?”

“No, because her circle of readers is not large enough.”

“But I thought she said she was a very popular writer.”

“The reader who reads poetry is a special reader, 30,000 printing of a book of poetry; now books have to cost much more than when her books were so low priced.”

D'Arcy: “Any huge publishing success in the last six months or 12 months in Russia?”

Glinka: “We have a very diverse book market of course. It’s very large. Detective novels have been very popular, adventure novels, and a lot of them are not very high quality. For example, Tarzan, books that have been forgetten about in the West. We have good science fiction. There were some good books published in the past. The Strugatsky brothers…” (science fiction; Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, best known for Roadside Picnic, 1972.)

Question: “Aware of realities of American writers?”

Borisova: “The difference is we have to operate here in opposition to something and you can operate there thanks to something. We know that almost no one in America exists only as a writer. In America, writers are supported lots of other ways: stipends, grants: we don't have any of that. That’s about what we know.”

Glinka: “Since we came here on a Sunday special, we are people who really care about the state of literature. I can see we all concerned with this not just warm but hot atmosphere in this hall.

I’d like to make a proposition to you, the most interesting way for another writer to visit another country is not in hotels and buses, but two weeks in a normal, in an average home. There’s a lot of us here who would like to enter into a writer’s exchange agreement. (I take care of foreign communication...)”

Wallis Wilde-Menozzi: “In the new situation, do you feel you've been given the space to say things as a writer that you couldn’t before? Space and energy inside yourselves as writers, not in the practical sense?”

Bransky: “We feel a deep inside freedom, so we can do what ever you prefer. So the answer for me is yes.”

Semenov-Spassky: “I’m a doctor and author of historical articles and scientific writings: I don’t find any new particular freedoms because I always felt free. I have many of my own problems, but they are not problems connected with…. “

Alexander Zhitinsky (big guy in a colorfully patterned sweater): “I've been listening here and not saying anything so let me start from farther away. We have been meeting fairly often with foreign writer colleagues. I feel like before we were like animals in a cage in a zoo with no visitors. Now we have visitors and they’ve opened the gates, but we’re still sitting in the cage, because we haven’t gotten used to our freedom. The cage is in our head. It’s an economic cage. To feel human and not just like an animal we have to have a convertible ruble. So I think our main imperative is to smash this cage and all of the zoo. So we don’t appear to you like some wild exotic beasts and you won’t be gaping visitors staring into the cage—the whole economic cage, and the cage in our conscience, but we're trying.”

Karalis: “I can't say I ever felt constrained as a writer. Half of what I’ve written could be published and half not. But I never felt offended by that. So in terms of my internal freedom, nothing has changed. But externally, I feel an enormous release of energy. I find I’m actually writing less and doing more other things. I created a small publishing house. I’ve been producing books on computer, desk-top publishing. I now have a bank account. So there is an impulse to try oneself in all these new areas that we didn’t have access to for so long.

Glinka: “I know for a long time, people in countryside hate me, because I live in the city, and workers hate me becuase they hate me because they had to get up at 6 o’clock and I didn’t. And officials of the party organization were suspicious because they didn't know what to expect of me. During the putsch I was away, I was in Germany; when I came back I ran into a friend of mine, and he says there were two feelings I had during the putsch, first there was fear and then a victory over fear. He thought that’s would he would say. For first time I am with someone else, no longer feel alone, there are others who feel the same way.

Borisova: “As far as literature goes, there’s no great change, because you know the worst editor I ever had always was myself. I had never had a more severe critic than myself. But I very much agree with Mr. Zhitinsky that the possibility of doing something or even the illusion that it’s possible to do something, it makes life a lot nicer, more attractive.

Gary: “What’s point of being a creative writer now?”

Borisova: “Because I really want to. That’s what we do.

(More talk outside the room.)

Karalis; his publishing operation is called Smart, a joint venture. His novel The Big Place, about a young businessman in the Andropov era. “Life is very interesting and many problems in government and many subjects in everyday life, we have no interest to write. Living is more interesting than to write. Karalis: A friend in Ohio, wants to write a book together about American and Russian traditions, in family and culture: James Kevin Herik, of Worthington, Ohio; book to be timed for 500th anniversary of Columbus.

Bransky (on translations): Some American authors were not considered ideologically suitable: John Updike, Salinger: Franny and Zooey—religious content, zen Buddhism. Some Henry James have been translated, some not; too much philosophical for the Russian audience. Standard as a translator: texts of stories in science fiction always profitable. Translating paid very small salary, considering the profit to the publisher. Once last: 24 pages typewritten, 5 rubles per page for the translator. Now 1000 rubles to the translator from cooperative publishing house. The market here is a wild market. Lots published already. Difficult to follow what has been done and what has not. I’m sorry to say this, but now going to publish another detective story. Just to say this is difficult. I like a writer named Eleanor Coerr (?), who writes books for children; from Canada now lives near Washington. To earn money I’m translating a detective novel by John Dickson Carr, to entertain myself I’m publishing her book about Kangaroo. Another agreement with a private publisher, simultaneously what I like and what I need to do.

“It was a state position, at the union, until Oct. 1, Russian Federation paid my salary. Now Writers Union Leningrad is trying to find money to pay people who work here. I could be unemployed. Head small department of 2 more people.”

The Remont Society: Of Cabbages and Cons

Nov. 4, 1991

It’s another siege of Leningrad: a city in the grips of hustlers and con men. Young boys rush up to every tour bus when it stops, offering cheaply made pins for chewing gum, dollars or whatever they can get. (Often they run up saying pin, and just like a Missourian talking, to refined Western ears it sounds like pen and someone in the group will hand them a writing instrument. They’ll take it anyway.) I offered rubles and gave a boy 20 for a handful of pins—an astronomical amount for such trifles but just two pieces of paper that cost me less than $1. This was when we stopped at the Peter and Paul Fortress, where, in the cathedral, we see the crypts of the czars and empresses and their children and kin.

The Metropole restaurant, where we ate lunch today was crawling with thieves and mafiosi. The restaurant was old world elegant gone to seed. The first floor bathrooms reeked all the way into the lobby and coat-check. Mosquitoes flitted about freely. But the spread was fabulous: caviar, chicken salad in aspic, beef tongue, tomatoes, potato salad in pastry cups, artfully carved eggs and four bottles of champagne on our long table. And that was just the first course. A bowl of cabbage and beef soup followed and then a beef and potato stew. We skipped dessert. I got swindled by a money changer outside the dining room, who wouldn't go away. I wanted to give him a dollar to scat. He got me up to $2, offering 60 rubles per. I knew he was pulling a fast one, but couldn't stop myself. He counted out 111 rubles, then threw in a 10 as if he were making a big concession. But he ended up palming most of with the oh, oh, don't look now ruse. I was had like the foolish American tourist I was trying so hard not to be.

Today's itinerary included the Peter and Paul Fortress. It was 4 p.m. and dark already so we didn't see much. Mostly walked through the cathedral, which like much else here was remont, undergoing repairs. An elegant, understated interior, much more so than the baroque candyland churches we have seen so far—St. Isaac’s especially and, from the outside only, the Church of the Resurrection. Also the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, where we lucked into an impromptu brief private tour from the priest, shortly before he began the evening mass. An exasperated woman came by and scolded him that it was time to begin. More candles burning before the icons; old women kissing the glass then touching their foreheads. One did both at the Nevsky sarcophagus, which is said to contain a few of the great savior’s bones. Outside: bent old babushkas begging and blessing those who gave—begging for themselves or the church?

An Opening for Opposition Media

Nov. 4, 1991

A dark-paneled board room at St. Petersburg radio and television studio: portraits of Lenin and Gorbachev overlooking the long table where all the Americans sit. The Russians take chairs around and behind us, against the walls.

This is the director's office, but they change so often we're not sure what to call it. “Alternative,” a program which all these people work for.

Vitaly Smolyin, Yevgeny Portov, producer and cameraman, who represents the management that no longer exists, Tatiana Kondravitz, filming meeting, an editor for Alternative. We're being filmed to be shown on television.

Alternative is “the most radical of the radical,” says a woman named Irina, producer of a number of programs here; been working since 1987; connected with Yeltsin. Opposition groups in Parliament who arose around Yeltsin; difficult to do that at first because we are part of official Leningrad TV. “Our producer here was taken off the air for two months after a program concerning Yeltsin and I was punished in another way (1989) not being allowed to travel abroad. But now I am president. and since August our situation has changed quite a bit for the better.”

Now, she says, we have a program 90 minutes on Sunday evenings. New channel begun in September. Just did program on Lenin and Revolution: A re-evaluation. This program is a present for the Nov. 7 holiday. Also program ``Business Contact'' twice monthly about problems with free-market economy. Twice a month we have an hour program on contemporary culture, including foreign culture, joint production with St. Petersburg LenFilm; and a monthly “Roundtable” about important issues.

Importing a program from Hamburg about Germany; advertising revenue will help buy equipment we badly need. German advertisers targeting Russian audience. We perhaps will do similar program here about Russia for German TV with similar advertising plan in reverse. Project: just getting off ground : 5 minutes opf advertising for revenue. Particulary interested in putting on air information of all political parties, because election is coming up, party-based. American company is consulting on political progrms, don't know its name. Sergei is a deputy on the St. Petersburg City Council. 70 parties. We have an audience<potential???> of about 75 million, broadcase reaches the Urals.

The official representative describes changes in prices for programs: latvians must pay 100 million ruble to receive programs and may not want to pay. Negotiations with other republics, southern ones, Georgia, Moldavia, for example, to carry Len. Tv. unique, pioneering effort.

Until recently, LenTV was under central control of Central TV in Moscow. That's now changing. We've been in hotspots; gone to Georgia. During putsch, representatives of KGB were sitting in this room. There were in offices of Len. City Council, and were preparing to take action. Len TV was taken off the air, showing Swan Lake from Moscow. Then information program from “committee on state emergency.” Producer filmed Len. City Council and got it to Danish TV, which showed it around Europe.

The basic top level leadership of Len. TV has been removed since the putsch. 2nd level of leader still in place does include old communists. They now call us witch hunters.

Sergei: proud that he was included, No. 66 on list of targets that putsch committee had drawn up. List was published in Arguments and Facts, Yeltsin was no. 69.

Been hearing a lot of a more serious coup in February. Sergei not sure. Thinks Yeltsin will handle things ok. “But it would be fun to cover.”

Gary refers to USA today story about AIDS in Russia and that no publication in Moscow, no education by media about such a non-political and vast health problem.

“We try to react to what we regard as the most imminent danger,” says Sergei, “We think of AIDS as a problem of the more distant future. There are guys on the streets with axes—more imminent danger.

Tatiana, been dealing with this in our editorial work...

Official guy: Alternative designed to deal with problems of political nature. Other programs deal with other subjects. Not always well, but trying to deal with problem of AIDS when question is raised.

Other sexual issues, editors and producers not always ready to deal with such issues. We do show material from Red Cross and films, or excerpts, from Hungary and France for example.

Yeltsin gave money he received in American royalties and honorary advance from book, bought needles for shipment from America (this in ‘89).

Cultural programs: “Birth of the Blues” in Russia; Brodsky.

“60 Minutes”--too respectable; different style, different technical capabilities. “90 Minutes” on Sunday, short; divided into 5 or 10 minute segments;

Alternative is a channel, a collective name for all of the indiv. programs. Preparing segment on Russian orthodox art.

Story on charitable aid from West being siphoned off by Army and others who are supposed to be distributing it. Make film about new fascists: V. Zhirivinsky<?>

Cultural producer working on project collaboration with guy from Len. film and Grace Kennan Warnicke of U.S. (CEC board honcho). Because textbooks are inadequate. working on video cassettes, a series of 40 tapes on Russian history and culture. Narrators are well-known experts. For example, leading literary scholars and historians leading these lessons.

So hoping that Slavic Departments in America and European universities would buy these series. So this would help us, and also would help you. We don't want to go with hands outstretched begging. Of course we need equipment.

City Council has created an independent, not govt., fund to help media. St. Petersburg Fund to Support Glasnost..

Yevgenia???: Saw during putsch how the free press worked...Those interested in free press here could contribute, guarantee survival of free press under whatever circumstances.

Anna...: Newspapers that do not have govt subsidies are in particular crisis right now. What's happening is even blackmail, Even government sponsored newspapers are threatened with ending of paper supply. Before used to be ideological pressure, not threat of taking way paper supply. Control of supply is in hands of Mayor Sobchak.

Former Len. Pravda has same editor, staff as before and has become paper of the mayor, and also is lowest priced. 30 rubles year subscription. Earlier very few people subscribed, but now because it's so cheap, people are subscribing. In fact the paper was against the name change, but after the putsch it’s become St. Petersburg News. New name, which was name of famous old newspaper.

Sobchak uses paper for his own purposes. Independent newspaper used to be a Komsomol Newspaper, Smirna, very critical reporting of mayor and recently told if kept up with have problem getting paper. So these newspapers are very expensive.

Official guy: I will give an example of cost of paper. In Karelia, 1 and a half years ago, a ton of paper cost 280 rubles. Four months later, sent telegram to factory, price had gone up to 460 rubles a ton. Then three months later 800. and now on the commodity exchange, it's 10,000 rubles a ton.

Black market

Official guy: Boris Markov.

Sergei: role of radio TV increased because newspapers having distribution problems and arrive three days late.

An average newspaper, 8 pages, 50,000 circ. uses 3 or 4 tons a week.

Irina (who serves as translator) works for “The Fifth Wheel,” which belongs to Moscow TV, she's music editor.

Alexander Suchomlin; music: we are nearer to Europe than America; he’s 20 and likes Dire Straits, Art of Noise and Depeche Mode (I saw graffiti somewhere in St. Petersburg: Depeche Mode written, in English, on a building wall;) I was disc jockey, now a producer director of a program.

He is happy when I give him a Duke Ellington cassette tape.

11/5

At the Hermitage

At the Hermitage, we must pay one ruble, 5 kopecks to take pictures. Other museums charge a dollar or two, but the Hermitage, we are told, does not have a hard-currency bank account.

We have a briefing with a senior research worker in the Hermitage department of prints, whose name I didn't write down. She took us down a hallway from the Intourist entrance, a corridor lined with crates, presumably holding art works being shipped or received, marked South Korea and elsewhere, pointing up, probably, the lack of adequate storage space in this huge building. Her answers to our questions seemed fairly perfunctory, or loyalist. Because of the lack of hard currency, new acquisitions come from inside the country; although the museum's tradition has been to acquire old masters, it now also is interested in modern art. As for the future, expansion, restoration, etc., “We have Napoleonic plans but they're too complex to implement.”

Parts of the museum will be closed for restoration and some holdings moved to the Marble Palace, now the Lenin Museum (also, same as the Menshikov Palace?). Plan to close the New Hermitage (or little Hermitage?, a 19th-century building). Winter Palace built in 1764.

When I asked about the concern in the West about the condition of the collection, she said, “Don't be worried. We have very good conservators. They are being taken care of. We have a very long tradition of that. Our concern is that because we have an intense exchange of pictures, we worry about them when they travel.”

David D'Arcy asks about the recent debate over repatriation of art that had been looted by Soviet troops in Europe. “Not everybody behaved with honor,” she allowed.

The Hermitage will not sell anything, she said, in answer to a question about the possibility of raising money that way. The Mellon collection, for one, is a museum that has many pieces sold by Stalin.

36 rooms of Italian art. Ugolino, gold background, early or pre-Renaissance. Fra'Angelico, Madonna fresco; a gorgeously erotic painting by Romano, includes three figures, woman on a couch, like an odalisque reaching out to the male nude, an older figure in the background--name?--I find Luvovnaya Stena, or schena written in my notes; Michelangelo, crouching boy. We race through, and now, two weeks later, I find much of the rest a blur; the impressionist collection was not as large as I was expecting, and I recall seeing, and photographing, I think, one painting that literally was falling apart, cracked and maybe peeling paint--a Degas or Renoir, I think, portrait of a young girl.

Channeling Dostoevsky

The Dostoevsky Museum was partly remont. Established 20 years ago on Nov. 11. In those 20 years, we are told by our guide, the common and official views of Dostoevsky have changed considerably. Dostoevsky, unlike Tolstoy, lived very humbly. Lived in Petersburg for 30 years, this was only one of 20 apartments he lived in, always as a renter. He liked large, cheap apartments. Moved into this one after the tragic death of his youngest son, because everything in the former apartment reminded him of his son. Moved here in 1878. On the corner of Yanskaya Street (Now Dost. St.) and Kuznechny Lane. After his death, his second wife pawned much of their belongings and left; only a few of the items in the apartment museum are certifiably theirs, others are genuine period pieces. His second wife was his 19-year-old secretary; he had four children, his eldest and youngest sons both died young.

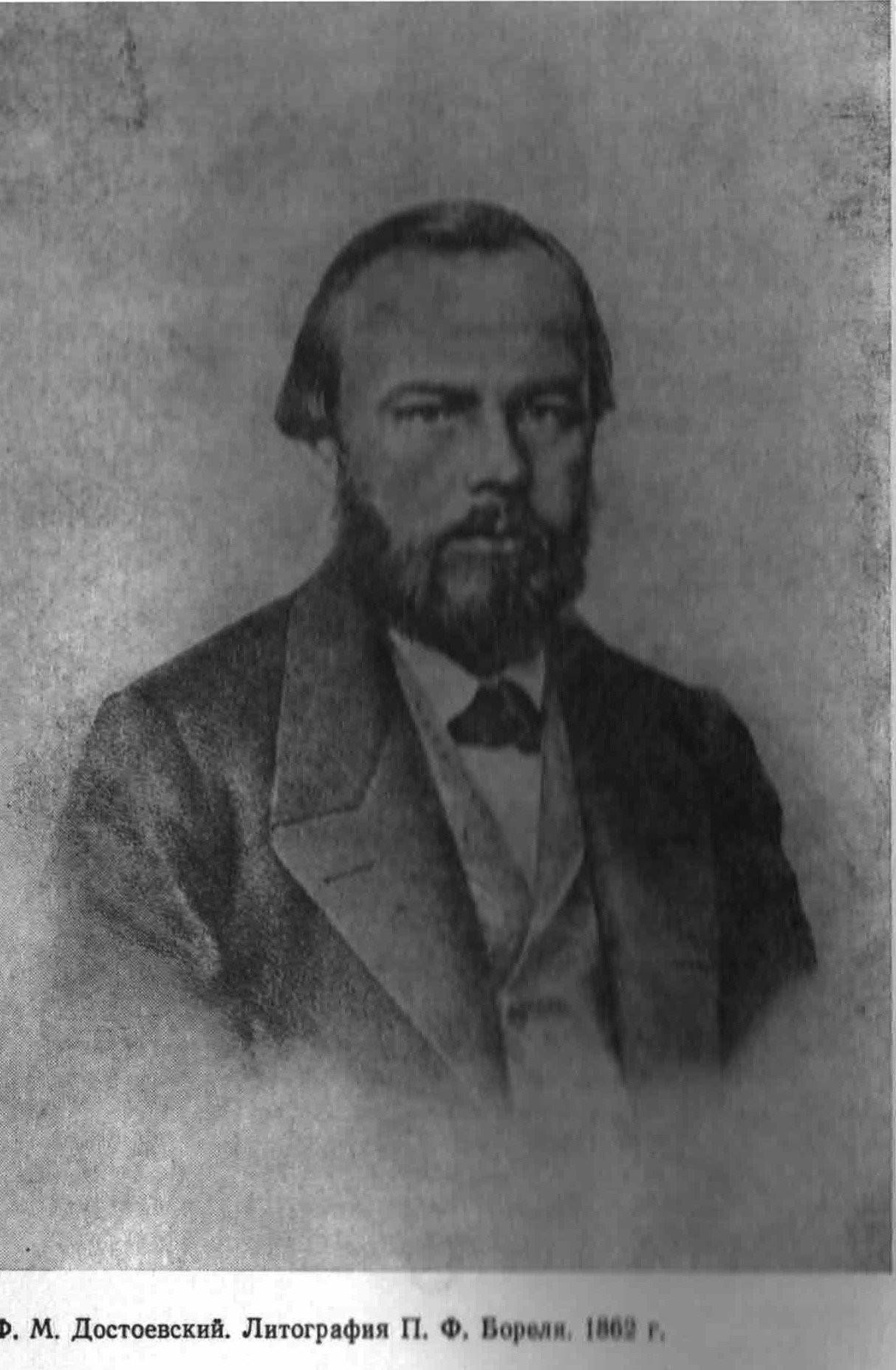

Dostoevsky

In one room, with a wooden desk with green felt, there is a note to his son, a ruler, eraser, some books--one by Gogol--a letter opener, pencil box, inkwells and paraphernalia, and a small shallow box open just enough to see a row of dice inside. Quite famous at this time of his life. Wrote at night, till 5 or 7 in the morning, then slept till 1; his children communicated with him by writing notes and slipping under the door. HIs wife's room; Tolstoy later said many writers would have been much happier if they had had a wife like Anna Grigoryevna; in the dining room, family together at tea; the rooms decorated in dark greens and beiges; with dark striped wallpaper. In the sitting room, or drawing room, where he greeted visitors, a red settee surrounded by matching chairs; a box of hand-rolled papyrosa, Russian cigarettes, which he smoked constantly. Then his writing office, roped off, but we could see the famous glass of tea that is always there on his desk. Drank tea and smoked incessantly while he wrote. Wrote most of Brothers Karamazov in this room. He published several journals, including Diary of a Writer; an icon on the wall, “The Mother of All Sorrows,” which he supposedly kissed right before he died. Kept a reproduction of Sistine Madonna over the divan on which he slept. Books in French and German, parquet floor needs finish. A glass of tea sits on felt-topped desk, which also holds a couple piles of papers, books, candle holders and inkwell contraption. Book case.

Russians by nature are very fatalistic people, our guide says, and Dostoevsky was no exception. Russian superstition: a way of telling fortunes. Give page number and line number, open book to that page and line. In the Bible, Dostoevsky got the line where Jesus is being baptized and John says, I'm not worthy of baptizing you. Jesus says don't hold me back, tell me the truth. He died at 8:36 a.m. on Jan. 25; the clock is stopped at that time. Tragic that as foremost writer, he was so poor the family could not afford a plot. Russian church donated plot at the Nevsky cemetery (closed the day we stopped there). A great grandson is alive, an engineer, and every year he participates in public readings. He was very popular, but then Lenin wrote an article calling Dostoevsky’s works arch, bad, unspeakable. The guide was taught Dostoevsky as part of a survey of literature. The Possessed published only twice during perestroika; was considered a parody of socialists; but it's much more complex and deserves to be read. Now The Possessed has become a bible for a lot of people and it's being read more than ever before. People are reading it as a guide to the way to live. He always was a leading writer but ideologists wouldn't admit, just like they wouldn't admit there was prostitution and unemployment. Tolstoy is not as contemporary as Dostoevsky, she says. Much more Russian reality in Dostoevsky. You read Tolstoy in your youth, but you keep returning to Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky is diachronic (accessible to all times), Tolstoy is synchronic (to its own time only).

Not long before he died, Dostoevsky delivered a famous talk at the Pushkin monument where he called Pushkin the first true Russian writer.

As we were waiting to go inside the museum, I was taken with a group of giggling school girls—giggling at my feeble attempts to speak Russian to them—and struck up a conversation: one charming 10th grader, with long straight blond hair, dimples and a sweet smile, could speak some English, much more than I could speak Russian. She told me they were visiting from Moscow and had been learning English for a couple of years, or maybe since 8th grade, Afterwards, while waiting to find our bus, I slipped into a little grocery across the street: the proverbial bare shelves had tins of fish, some cheese and butter, a few sausages and in another room some less than fresh persimmons, which seemed to be the fruit in season wherever we were. Short lines of exasperated people, but I didn't get a good sense of what they felt.

Almost Boppin’

At the Jazz Club; a video showing clips of Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan, Ella; photos of Basie, Armstrong, Lester Young and others lined the walls. We pick up a slab of salami on hard white bread along with glasses of cognac at the ruble bar. The saxophonist who led the quintet (piano trio plus congas), and apparently owned or ran the club, had some chops but was a bit stiff (lacking soul). They played mainstream midcentury American jazz: “A Train,” “Body and Soul,” “Don't Get Around Much.” His name is Galyushkin, or something like that; he switches to an electric violin for “Body and Soul.”

In the hallway outside the balcony, I discover an art show going on, and wind up meeting the artist, Andrei Zakirzyanov, whose paintings are far more accomplished than anything we saw at Mazin's building last night. In a halting conversation with the artist he tells me, “I study at the Academy of Fine Arts because I don't want to go into the Soviet Army.” [2021 note: I found this online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/art_by_andrey_zakirzyanov/]

He introduces me to the sculptor Oleg Podberiozny, who also has a few pieces on display.

Andrei talks about his work; he uses biblical themes in his somewhat ambiguous, vaguely figurative surrealism and very textured and layered pieces not for religious reasons, but because, I think he is saying, the Bible has ideas that are universal and speak to the problems of all humanity (his phrase). He says there is an effort to create a new system of galleries, spontaneous, ad hoc, maybe run with artists in mind rather than the whole dealer-and-sales schemes. I tell him I had met Mazin and the young artists the night before—Mazin had been somewhat dismissive of the academy—and he in turn dismissed that group as “commercial artists,” implying, I gather, their shameless catering to the fawning dealers from the West. He refers to another, Mikhail Shmaikin, and says he does more interesting work when in this country than when out.

Another man who helps to interpret the conversation turns out to be a journalist or news broker of sorts named Korotkov, who has come up from Moscow with a cameraman to do a documentary on St. Petersburg and the coming holiday that will mark the name change (formerly the October Revolution holiday and now announced with street banners here as Viva Saint Petersburg). Turns out he is a former Tass man, now on his own with various video and publishing ventures (newspapers, monthly magazines, a second office in Kiev). Even while at Tass, he said, he supplied the West with material he wasn't able to use on the official channels. Even though Tass is undergoing its own change, he said, “it will be propaganda again,” so he and his partner decided to go out on their own, to create their own agencies.

I also meet a couple of young Americans and a Brit who are here teaching English in a business school.

Somebody, I think the Russian named Eugenia who was the friend of Amy, the American from San Francisco, tells me about a film named “No Return” by a guy named Sneshkin, shown on Leningrad television; it was made just before the putsch and was about a coup that might happen in the future. (It occurs to me later, this must be the film made from the novel by Karbakov, of Moscow, which he hated.)

Before we leave the jazz club, we get a chance to hear a singer who has joined the group. She sings ``Lullaby of Broadway,'' and it's several measures into it before I realize she is singing English. A very mannered style, shaped words like Flora Purim singing English; a blond in a, flouncy blue on white polka-dotted dress.

On to Odessa: Uncertainty in the Ukraine

11/6-7

Walking the streets of Odessa near our rather decrepit hotel, the Chernoye Morye, people seem to be more prosperous. Food appears to be more plentiful in the shops. There is even a rather nice looking restaurant across from the hotel, which at lunchtime one day, was attracting a well-dressed, professional clientele.

There is talk that the name of Pushkinskaya Street will be changed back to its pre-revolutionary name, Italianskaya, which reflected the influx of Italian businessmen and others 100 years before. Like St. Petersburg, much of the grand architecture was designed by Italians, although the gorgeous Opera House was done by two architects from Vienna. Our guide, Igor, tells us that many of the buildings are similar to those you'd find in Southern France or Italy, a fact confirmed by some of my well-traveled tour mates.

The Ukraine is home to 85 nationalities and ethnic groups. All of them, it seems, want their own homeland. Later, some of the journalists will tell us that nationalistic tensions here are less severe than in neighboring Armenia or Azerbaijan or elsewhere; they think their problems will be solved much more peacefully and with independence may end up apportioning various ethnic regions as states within the country.

In the last two or three weeks, Igor tells us, prices have begun going up. Until recently a bottle of vodka could be had for 12 to 14 rubles; now, there's none to be found, but it's expected when it becomes available again that the same bottles will be going for 37 to 42 rubles.

Tomorrow, the 7th, of course is the holiday of the October revolution, but it's quiet. No one will be celebrating, Igor says, there won't be any parade of communists. Igor says he'll be home making repairs to his apartment, although he does join us Thursday for our private tour of the Literary Museum.

Igor is quite frank and open with us. The people, he says, feel cheated. There's no good mood. New Year's is coming and there is money. “We are free to vote, free to talk, free to kill each other, but not free to live well. We can hardly find any medicine in the drug stores.”

He goes on: “Everywhere and everything are controlled by the mafia. There is no help and everyone is quite depressed. No one to lead us out. Not Yeltsin, not anyone. All people are waiting—what is next, what will be next? There are 1,000 ways to make money in this county. But to be an honest, good, diligent worker gets you nothing.”

From the notebook: Odessa is agreeable to walking. Chernoye More, a seedy hotel, with buggy rooms, small, few services; a sleazily charming supper club has a floor show with dancers, tangoes, g-stringed duo with chairs, glitter and Vegas facade.

“Not a toilet”: a sign seen more than once at the sidewalk entrances to courtyards behind the building; bread, ice cream, sycamores (plane trees?); gray, the swarming gangs of boys trying to sell postcards. Wouldn't take no, emphatic nos. Egged on by an older kid — a Fagin, someone says — to go back and harass us some more.

The merchants in Moscow (later), outside the hotel, in Red Square, are much more polite and apologetic. They approach once, show you their watch, or doll or chess set, and after a polite “no, thank you,” they leave you alone.

Dinner time becomes a bazaar. The waitress offers caviar, floral woolen scarves. Elsewhere it has been amber necklaces. all at quite favorable prices.

New Directions Are Wholly Unclear

11/6

A meeting with journalists, writers, city council members and others at the Student Center in Odessa.

Participants include:

*Alexander Milkus (sp?), a reporter for Komsomlskaya Pravda, who also works for the newspaper put out by the mayor's office; interested in criminal affairs, economics and politcs.

*Viktor Spiridov, Odessa News; Igor Rosov, editor for Odessa News; Boris Vaitzma, phd physics; Grigori Klener; economist; Yuri Vyatkin, economist who works with computers; Sergei Kazmaku, deputy director of this space; a city coubcil member interested in religion, cutlure and politics; a journalist, phd. in medical psychology and member of city council—“I am for one party, independent”; Susanna Alperina, who organized the meeting for us, and Alexander's wife, also a journalist, who formed an org. of businesswomen.

First speaker: Before the revolution Odessa was the third most important city in the Russian empire; lost some influence since then. Economic situation in entire country is rather difficult, after breakdown in relations with the Union and other republics. Alexander says there’ll be problems this winter with food supply and heating. Taking more responsibility for ourselves. Seeing a privatization of stores here earlier than elsewhere. Anticipate 80 stores selling vegetables will open this winter.

In the Dec. 1 election, not one candidate is contemplating serious economic reform. Even though the Communist Party doesn’t exist any more it still controls many economic structures. Regional party leaders still calling the shots, and communists trying to create structures in four areas of Ukraine to maintain the power. Two hours away in Moldavia, troubles are being fanned by the party. New Independent city structure in Odessa trying to create opposition to the apparatus. Trying to draw up legislation creating free economic zone. Hopeful attracting interest of western business.

Second speaker: To say that we don't have food is not exactly true. There are 7 million tons of grain left in the hands of peasants who don't believe in the government. (I hear today on NPR, 11-23, a story about how farmers already are diverting their grain from officials channels to sell them privately on the market, which they've discovered brings them more money.)

Some parts of Ukraine are more nationalistic than others. Anxiety is fanned by former communists; all leading to question: was there ever a Ukraine anyway? Some say no.

One person suggests that a solution for dealing with the mafia would be

for the republic to enact legislation that relates to private property that will free me of the necessity to engage in illegal activity.

Barter economy makes more sense because money isn't worth anything.

Political parties are modeling party organization on former communist party. “We all came out of Lenin's overcoat”; paraphrasing Dostoevsky on Gogol.

Always had corrupt structure. Always had a deficit in this country. For 71 years. The old state was a mafia in itself. This gives way to a new type of mafia.

[My question:] How long will it be for economic reform to work, how much patience do the people have?

Deeply convinced the situation in the Ukraine is better than in Russia. Maybe a little worse than in Byelorussia, but generally I don't fear an explosion here. I think three years minimum for situation to stabilize and 10 years to reach the level of the Congo.

The two serious candidates: Chernovo and Kravchuk; Chernovo a former dissident who spent 16 years in prison, he's in favor of the German model for Ukraine, with separate states.

Susanna Alperina: Our cultural life is at a boil. New publishing, lots of books coming out at author's expense, which we were not able to do before. The book market here has become more interesting. One of the only areas we have a free market in is books, maybe film and theater. It was aspects of culture, that first opened the free market.

“Grafoman.” Alexander explains that publishers will pay for publication if they think a manuscript has commercial potential. If they think the writer is a “grafoman” (a scribbler), they only will publish if the author pays.

Communists not looking at religion—orthodox ideology suitable for thinking of new ideology. (I think we hear elsewhere that hard-liners may be encouraging the churches, because religion promotes a kind of submission).

Religion has come into fashion. It's a fad. At Easter Yeltsin and Pavlov were very visibly seen going to a church. One now in prison and one now president.

The problem is to save our culture, education, our society, we must have help from the west.

Memorializing Writers: Odessa Literary Museum

11/7

Although it was the holiday, and the museum was closed, we were given a special and quite thorough guided tour, led by one of its staff members — a “scientific research worker,” or academic literary historian, whose name I don't have.

The building on Pushkinskaya Street was a palace built in the mid-19th century and owned by a Count Gagarin, built not as a residence but as an arts salon. It's very large and each room is designed differently—an inlaid, parquet floor in one large room; a small room whose walls and ceiling are covered by plaster grape vines. Gagarin gave the building to the city at the end of the 19th century. (2021 note; see: https://museum-literature.odessa.ua/en/museum/)

The museum is 15 years old, and contains 40,000 items, we are told. I think before the end of the two-hour tour we may have seen each and every one of them.

“The museum tells the history of literature and literary men who lived here or passed through.”

In the first grand hall, Chekhov and Bunin met people. Chaliapin sang here. A white and gold decor with the finely inlaid and parquet floor.

Bubble-covered exhibits show something of the theater life of the time, containing scripts by Pushkin and Gogol, and newspapers.

From here the tour proceeds chronologically. The second room shows the first two decades of literary life here at the turn of the 19th century. Period books in French and Russian. The royal order that established Odessa as a Porto Franco. Copies of Lyceum magazine from 1806; the first book printed about Odessa, Par Sicard (whatever this means) a portrait of Richelieu.

A quote on the wall, done in raised lettering like metal type, from Pushkin (translated by Margarita): “The part of the country has southern sun, it has the beautiful seas as if this place is blessed. What else can a man need?”

In the 1820s Odessa was a bustling European city. Many of the displays from the time, for example, include books in French from the first book store here: Rousseau, Byron, La Dame du Lac, Voltaire.

Pushkin arrived here 1823 and stayed 13 months, an important span that exposed him to European art and literature. He wrote his Southern Stories here, and many poems, and began Eugene Onegin, in which he describes the city.

The first magazine published here was bi-lingual: French and Russian. 1827: Odessa News; in 1831 they began publishing separate editions.

The grape-vine room is meant to look like a bookstore of the time.

Gogol, our guide says, “wrote in the Ukrainian spirit although he used the Russian language.” He came to Odessa a year before his death, and he was already quite sick, mentally and physically. He created his second volume of Dead Souls while here. Decided he couldn't write as well as he did in the first part. Lived as a hermit. A display has a written copy, by someone else, of some chapters before publication. Above us is a tumbleweed suspended from the ceiling, from the steppes where Gogol grew up.

Belinsky: a noted literary critic, who lived in Odessa for six months./p

Hall No. 4: the 1850s, the tragic years of the Crimean War (1853-56). Tolstoy spent a few days in Odessa on his way to Sevastopol, and we see a pair of epaulets like those he might have worn as a senior lieutenant in the Russian Army. At the time he was trying to decide whether to stay in the military or to write. Shortly after the war he published his Military Stories (later called Sevastopol Stories) and made the decision to go on writing.

Sovremenik (Modern Man), a journal published by two noted critics, Cherneshevsky and Dobrolubov. Another journalist, writer, was Korolenko, who encouraged the founding of the Esperanto Society. No surprise, given its multi-cultural background, that Esperanto Society was founded in Odessa. (My encyclopedia, however, credits Dr. Ludwig L. Zamenhoff of Poland with inventing the language and first presenting it in 1887.)

Yiddish writers Sholom Aleichem (a very tiny display) and Mendele and Moicher-Sforim.

Journalism-newspapers presented in an eye-catching display that popped off the wall. Literary magazines: Life of the South and Southern Notes. B.M. Doroshevich, known as the king of Odessa journalists. He wrote for Odessa Listok, which readers quickly snapped up because of his often bitter and funny articles (1864-1922).

After writing a particularly satirical piece, he moved away within 24 hours but managed to return a year later (c. 1888).

Doroshevich wanted to repeat Chekhov's Journey to Sakhalin, the remote penal colony. He had to disguise himself as a vagabond to make the trip, because after Chekhov, authorities limited travel there. When he was finally discovered, however, he was allowed to go on, without his disguise. His book How I Got to Sakhalin appeared in 1903, a year before Chekhov's death. Chekhov visited Odessa a few times. His plays were staged here, and he had friends here. His story “Grasshopper” is the true story of a young Odessa girl who died saving a patient, a young boy. Olga Vassileva, a rich young woman who loved his work, gave Chekhov her house when she left for London. He later sold the house and gave the proceeds to medical charity. She wrote often to him and later did the first translations of his work in London. Chekhov: “An invisible force attracts me to Odessa.”

Where are majority of Russian literary archives? Central Archives in Moscow, Pushkin's House Museum in St. Petersburg.

Gorky was a stevedore in Odessa and lived not far from the museum in a flop house. His first stories were about life on the Odessa port.

Mayakovsky: “A Cloud in Trousers,” a poem inspired by his Odessa experience, and a woman named Maria Dinisova, who also inspired Isaak Babel and Alexander Tolstoy. She from Russian nobility, who married a Red Army officer and was kicked out of her family's house. Followed her husband on horseback and lived with him in a tent. Widowed young. A. Tolstoy's “Serpent” is about here, as is Babel's play “Maria.”

A hall dedicated to the revolution.

A literary union called The Green Lamp, 1920s and '30s.

Yuri Olesha. Edward Bagritsky, a romantic poet. /p

Museum filled with lively three-dimensional displays, glass-covered boxes, bubbles, dynamic angles and wall graphics. Pertinent quotes are stenciled on glass or on the walls or even the ceilings in a couple of rooms.

Of Babel, our guide said his literary fate and his human fate are quite certainly tragic. Subject to repression and killed. Until recently his works weren't published. Yet he was honored here, published a lot here now. Two years ago, the museum held a reading of his works, which has become a regular occurrence. We see his eyeglasses and fountain pen in a display; after his death most all of his belongings were confiscated and destroyed. Babel went to the first Writers Congress in 1934, shortly after which he was arrested.

11/7

On the anniversary of the October Revolution: The television in the bleak lobby of the Chernoye More shows a reporter at Red Square in Moscow pointing out the quiet streets. There is no celebration there or here. Later we will hear that perhaps 5,000 communists paraded with their red flags at a demonstration of old-line Lenin loyalists in Moscow.

Igor tells us news of yesterday: the Ukraine signs an economic agreement with Russia. This economic war will settle down soon, he says.

11/8

We leave the hotel early, just after 6 a.m., for our Aeroflot flight to Moscow. I seem to remember nothing (writing this two weeks later) of the airport in Odessa, which we traveled through twice, although this might be where we lined up for tea and juice to drink with our packed breakfasts. I remember arriving at the international airport in St. Petersburg, a dingy place; and the domestic airport there where we had breakfast in the dark on the morning we left for Odessa. Arriving in Moscow from Odessa we notice that all our bags are have tags destined for Budapest (BUD): only on Aeroflot, I think. And when we leave Moscow from the international airport, after the duty-free shopping and Wallis' last minute scrape with the uncooperative authorities over her photocopied visa, we have the humorous scene on the tarmac, standing at the foot of the stairway and finally being told, this is the wrong plane: we walk under the nose and go two planes down where we are allowed to board.

In Moscow: the media now calling the revolution the coup of 1917. Our Cosmos Hotel, built by the French for the 1980 Olympics, a huge, 3,000 room building. No one has lived in the Kremlin since Stalin.

At lunch the waitress offers to change dollars for 52 rubles apiece--the official rate is now 47.

Bus driver tells about standing in line for two and half hours for bread yesterday. Moscow seems quiet on the second day of the holiday.

At Lubyanka Square, we see the headquarters of the KGB, the empty pedestal on which the statue of KGB founder Dzherivinsky had stood and which has now been pulled down. Nearby is the Solovetski stone from a monastery in northern Russia, which was turned into a prison after the Bolshevik coup and where victims were persecuted. Yesterday there was a memorial service there, where people prayed and a priest conducted a burial service for the victims of the Bolsheviks. On the same day the old communists rallied at October Square around the Lenin monument. They feel that Gorbachev and Yeltsin have betrayed socialist ideals.

“Some say we are on the verge of civil war,” Lydia, our Moscow guide says.

Food coupon system; rationed meat milk, bread at state prices. Also will be some available at free market prices.

At the Cosmos newsstand I see a copy of Lee Iacocca's book in Russian (I recognize his picture and his name in cyrillic: Lee Yakokka; the title, in cyrillic, says Career Manager.

“It's an unpredictable country,” the newsstand cashier allows when explaining that today's paper's might be late.