The Hemingway Society international conference in 2004 lured me to Key West for the very first time. At that meeting Gail Sinclair and I had cooked up an idea and introduced a proposal to hold the 2008 conference in Kansas City. Below is a (possibly unedited) draft of the article I published in the Kansas City Star, with a dateline from Key West.

Gallery photos above, all (c) Steve Paul, from Duval Street, the Hemingway House and the Key West Art and Historical Society (Hemingway’s uniform)

By STEVE PAUL

KEY WEST, Fla. – Harry Morgan, the angry boat captain at the center of Ernest Hemingway’s 1930s novel To Have and Have Not, struggled against the forces of economic change.

Even then, Harry sensed the coming ruin of Key West, a transformation in which some unidentified “they” was displacing the poor locals and turning the salt-of-the-sea place into “beauty spot for tourists.”

Harry undoubtedly would howl today at the sight of the nightly sunset revels in the heart of touristy Key West, the self-proclaimed “Conch Republic,” where the largest thing in sight is a cruise ship, all out of proportion to this fragile spot of faraway land.

Near the end of a string of islands that arcs southwestward from the southern tip of Florida, Key West also happens to be situated on the Hemingway Archipelago, a chain of alluring places around the world that still resonate with artifacts of the writer’s life, his spirit or his literature.

And so Key West was the spot where some 250 scholars, devotees and members (as I am) of the Hemingway Society gathered last month for the organization’s 11th biennial international conference. Attendees came from 11 countries, it was announced, and spent a week delivering and listening to scholarly papers when they weren’t snorkeling or sipping fruit-and-rum concoctions on the beach outside a comfortable resort hotel in the quiet southern corner of the island.

Well, there was more than that, of course.

For a couple of dozen people the session included a cosmic high point one blustery morning at the end of a pier. They’d gathered at sunrise to witness the Transit of Venus, a rare alignment of planets that last occurred in 1882. Telescopes came courtesy of Joe Haldeman, a prominent writer of science fiction novels (The Forever War) and such an ardent Hemingway follower that he once wrote a novella about a dastardly effort to publish a bogus piece of Papa’s work (The Hemingway Hoax).

One attending graduate student had the brilliant idea to lug his worn copy of Thomas Pynchon’s gargantuan novel Mason & Dixon onto the pier as we watched the black dot of Venus cross the face of a brilliant yellow-orange sun. (His book bore a thick fringe of day-glo note flags, the sure sign of a dissertation in progress.) Mason and Dixon were 18th century British surveyors, and on a June morning at the Cape of Good Hope, they, too, witnessed the Transit of Venus. As Pynchon has it:

Upon first making out the Planet, Dixon becomes as a Sinner converted. “Eeh! God in his Glory!”

“Steady,” advises Mason, in a vex’d tone.

Ernest Hemingway’s Key West years spanned 1928 to about 1939, and although there was much happiness as he plied his “twin trades” of writing and fishing the Gulf Stream, his life there ended up anything but steady. His second marriage dissolved as his affair began with future wife No. 3, and, not long after the highway finally reached the island, Hemingway left for good to take up residence in Cuba.

Hemingway’s writings from the Key West period – including A Farewell to Arms, Death in the Afternoon, To Have and Have Not and a slew of his finest short stories – were analyzed, deconstructed, explained and reimagined in the conference’s daily paper sessions. Hemingway’s spiritual leanings, his friendships and rivalries, his work’s racial conundrums, his fishing logs – the Hemingway territory is vast.

Susan Beegel, editor of a twice-a-year scholarly journal (The Hemingway Review), connected Key West, Hemingway and Harry Morgan to the history and literature of piracy, the table in front of her draped for the occasion with a skull and cross-bones banner.

Miriam Mandel, an Israeli Hemingway scholar, demonstrated the workings of Hemingway’s “iceberg theory” by explaining how three sentences in one chapter of Death in the Afternoon embedded a decade of labor unrest and violent repression during Spain’s revolutionary convulsions of the 1920s.

There were feminist/Marxist papers and Freudian papers and one paper that performed a typical bit of academic acrobatics by discussing Harry Morgan in the context of “masculinity in crisis” and linking him with Edward Norton’s character in the macho-mythic movie “Fight Club.”

Several talks addressed one of Hemingway’s most overtly political writings. He wrote “Who Murdered the Vets?” in the aftermath of a hurricane that ripped through Matecumbe Key up the way, killing 458 military veterans who’d been sent there to do “coolie labor” at low pay and without regard to their safety in the storm season. Reading it today, Hemingway’s hot-headed essay might put one in mind of a Michael Moore-style “f-u-mentary.” The resulting divisiveness is similar, too. Indeed, one scholarly detractor suggested that when Hemingway wrote it he must have been drunk.

“When you go looking for ghosts, ghosts rise up,” Lorian Hemingway, a granddaughter, said one afternoon when she read from her memoir about a spiritual journey that took her beyond the bottle and into fly fishing.

And if the ghost of Hemingway were hovering in the halls of the Casa Marina Hotel, he might have been startled to encounter a doppelganger in the form of Lawrence Luckinbill, the actor, who’s in the midst of developing a one-man Hemingway show. Luckinbill, tall and round-faced and sporting a mostly white beard, last year staged a onetime performance, but, after failing to acquire the rights to use excerpts from Hemingway’s fiction, he rewrote it based on Hemingway’s prodigious and famously expressive letters. (Under an agreement put in place years ago, Hemingway heirs control publication rights of already published books and unpublished manuscripts, and the Hemingway Society and Foundation holds rights to letters in public collections.)

Luckinbill’s 75-minute staged reading portrayed Hemingway in his last hour, the dark and troubled mind racing through memories, unable to draft a single sentence and about to signal his finger on the trigger. As Luckinbill and everyone else knew, he couldn’t have found a better or more brutal audience. Those who knew Hemingway so well were unrelenting in their feedback that night and over the next few days. Luckinbill plans to mount a version of the play in New York in December, and it will be fascinating to see how the play evolves in the wake of all that informed and passionate response.

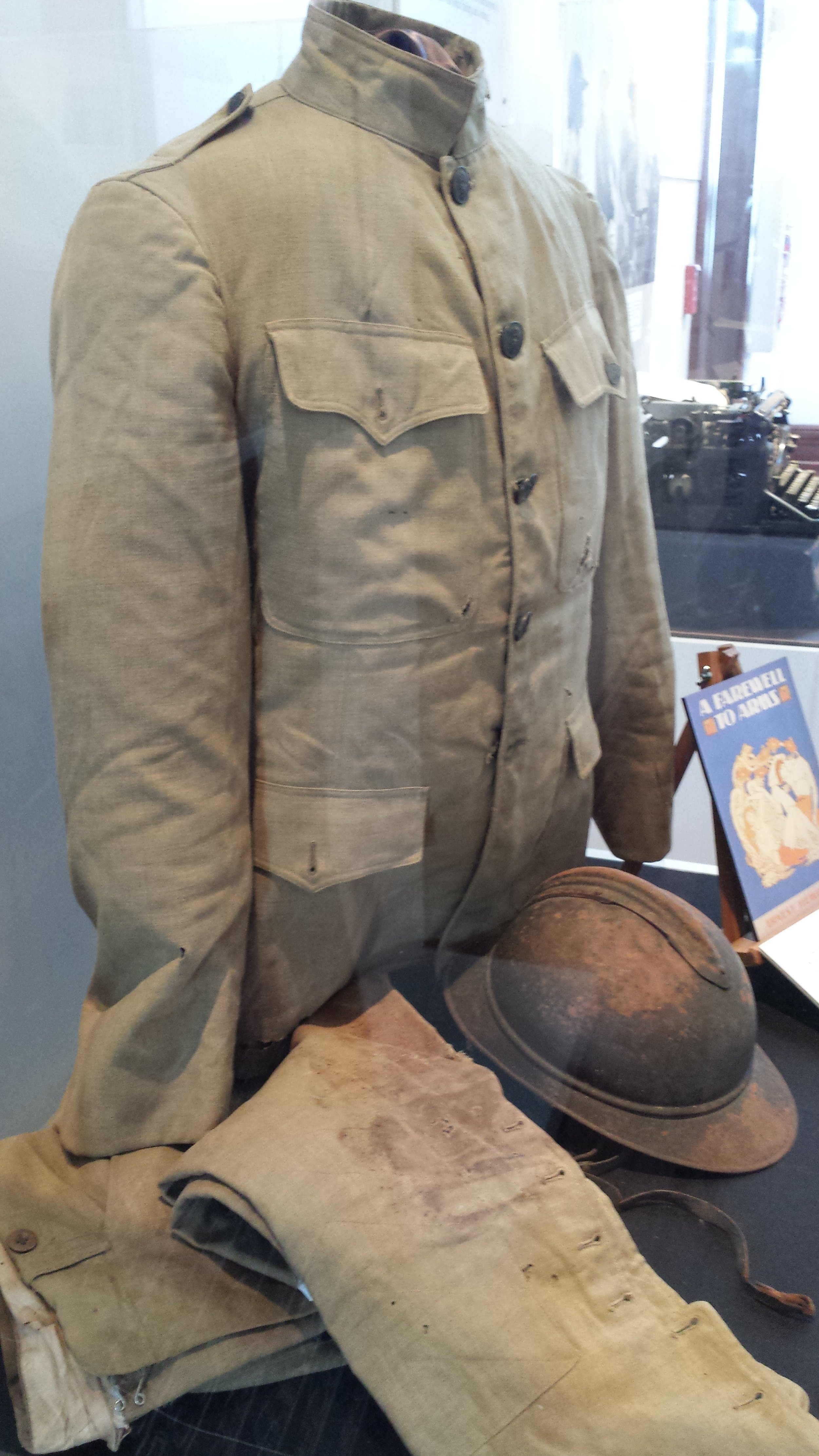

The Hemingway house in Key West remains a major tourist attraction, with its tall windows, its huge trees and its swimming pool, but for a credible sense of Hemingway’s history, you have to visit the Key West Museum of Art and History at the red-brick Custom House. The museum maintains a collection of Hemingway memorabilia, including, astoundingly, the tunic and breeches he apparently wore on July 8, 1918, near the Piave River in Italy when first a trench mortar exploded and then a round from a machine gun tore into his right knee. The uniform is carefully arranged in a display case to show off the faint red stains still visible in the leg.

Also on display (for the rest of the year) is an important collection of nearly four dozen photographs taken by Walker Evans in Cuba in May 1933 during a period of rising unrest and repression. Evans and Hemingway met then, and Hemingway is said to have carried the photographs by boat from Havana to Key West. The prints were found in a cache of Hemingway belongings that were long stored in Key West and only recently came to light.

The weekend newspapers made it clear that the Hemingway legend lives large in Key West, without even noticing that the scholars were in town. One story touted the forthcoming annual Hemingway Days Festival, centered on the writer’s 105th birthday anniversary, July 21, which promises the requisite lookalike contest and other folderol. Then there was the feature story about polydactyl felines, or “Hemingway cats,” the ones with six toes or more. Whether Hemingway actually owned six-toed cats in Key West – knowledgeable sources says he didn’t – is immaterial in a world that can’t stop believing he did.

But more interesting was a letter to the editor of the Key West paper. A man complained about a fishing contest in which he’d just competed. He’d failed to win because of some weigh-in snafu. The man was a boat captain, and in his anger over being jerked around by the system he sounded more than a small bit like Harry Morgan. Yet more evidence that some things never change, even in Key West, and that Hemingway’s aim was true.