I’m on the returning-home side of the Folk Alliance International conference in Montreal. It was my sixth annual immersion into the global music gathering, which unites an uncommonly diverse collection of people through the power of song. You can measure its value by way of any number of fronts: Discovery, preservation and promotion of cultural traditions, inventive reworkings of those traditions, nostalgia, memory and celebration of craft – be it instrumental mastery or the writing of songs. All of those things defined my Folk Alliance experience once again.

I’d gotten hooked during the last five years of conferences held in Kansas City. I found it in part to be a place of hope and determination for hundreds of young musicians who have turned their passion for music into their life’s path. Until you walk the hotel halls late at night in the midst of a kind of musical speed dating extravaganza, you might not get the full picture. There was more than one moment when I wondered about the life-span of an emerging musician’s career. How long does it take to convince someone they have or have not found an audience for their music? I’d be curious to learn whether anyone has studied the subject. Then again, when you have the voice and the song-writing vision of some of the reigning superstars of folk, the answer is self-evident. Joni Mitchell, who, as a Canadian, was a guiding spirit in absentia of this conference, recently turned 75 and her lifetime’s work was duly celebrated in a Los Angeles concert last fall. Eric Andersen, who turned 76 here the other day, has been at it for nearly 60 years, though his rich, deep-amber voice is not always what it once was. After Livingston Taylor announced from the stage one night that he first began performing 50 years ago, I was able to tell him, that, why yes, I saw him for the first time 50 years ago, in one of the free Sunday concerts on the Cambridge Common where I fanned my folkie, guitar-picking flame.

Some of my favorite Folk Alliance experiences, aside from the comfort of memory lane, involve discovering new sounds and ancient ones for the first time. The conference highlighted numerous indigenous cultures, including musicians from all across the vast continent. Not a day went by without a welcome message that included the acknowledgement that this piece of riverside Canada was “unceded territory” of the Kahnawake Mohawk, a gesture of an ongoing reconciliation project to amend for centuries of imperial genocide and cultural suppression. Typical of the contemporary indigenous performers was singer-songwriter Adrian Sutherland, who, along with his own songs, covers (Canadian) Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” and adds a verse in his native Cree dialect (find it on YouTube). Buffy Sainte-Marie was handed an award for being who she is as a musician and political activist practicing and stirring controversy at least as long as I’ve been listening to folk. Another northern Canada surprise was the punkish trio of Josh Q and the Trade-Offs, who rocked a small hotel room packed with fans.

It seemed like an honor to encounter the world of Inuit music, which combines drumming, dance and the tradition of throat-singing from the far north. A performance by the ensemble Arctic Song was a revelation. But beyond that, hang around long enough and it’s possible to learn something, as I did in a conversation with a Canadian ethnomusicologist and during a seminar session led by two throat-singing practitioners. For one thing, the art is not ritualistic or spiritual. It seems to have stemmed from women in the culture, who had time to fill at home when their men were off fishing and hunting. For some it was body language that bonded them with their babies. It also became an aspect of play and competition, enough so that some scholars consider the music to be not singing per se but “throat games.” I can’t begin to describe the sound in words other than it combines breath, rhythmic vibrations and guttural expressions that reflect the natural and animal lives surrounding the people of the Arctic or Canadian tundra. I loved the description of one song that suggested that if one painted the sound of the wind the music would stem from that.

As if that weren’t discovery enough, it was rather eye-opening to learn that Arctic throat-singing had no relation to the throat-singing I’d encountered over the years from some Central Asian cultures. And sure enough, a throat-singing trio from Tuva in the Russian Federation was on hand to emphasize the point. Their performance was astounding and thrilling in the moment.

Folk Alliance creates community and friendships in abundance. After an evening of multiple showcase concerts, the action turns to three throbbing floors of the host hotel with poster-lined hallways and room after room of private concerts that run, officially, until about 3 in the morning, though often much beyond that. Musicians can play to an audience of one or to an impenetrable crowd, and it all ebbs and flows as players trade off every 20 to 30 minutes. Some rooms are corporately sponsored, by record labels, agents or cultural organizations. Some become ad hoc house concerts. Serendipity rules. I don’t usually feel guilty slipping out of a room when the music doesn’t move me. And it’s rewarding to come across musicians whose sound I wanted to hear more than once and who didn’t mind at all that I showed up to their private showcases like a regular. Among those now on my radar and playlists are the jazz-inflected duo of Jenna Mammina, a singer, and Rolf Sturm, a guitar phenom; the singer-songwriter duo of Freebo (the onetime bassist for the likes of Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne) and Alice Howe; Sam Lynch, a dramatically expressive young woman from Vancouver, B.C.; Melanie Brulée, a high-energy, country-fied singer and songwriter from Toronto; and the Black Horse Motel, a band from Philadelphia that features hard-driving songs fueled by dobro, fiddle and a drip-painted cello.

Jenna Mammina had never met Reggie Harris before, but her guitarist knew him and got him to join her in a song — George Harrison’s “Give Me Love.” This turned out to be a miracle photo, snapped as they sang the last bar.

More serendipity brought a stirring solo session by singer-songwriter Maya de Vitry, now of Nashville, whom I’d heard in previous years with her band the Stray Birds; a global jam session that accrued around the harp and voice of Kansas City performer Calvin Arsenia; and a totally unexpected rendition of Radiohead’s “Weird Fishes” by the joint forces of two guitar trios, one from Los Angeles, one from Montreal. Yes, almost anything goes at Folk Alliance.

Other choice moments came from hearing the slide-guitar blues of John Kay, better known perhaps as the founding voice of the ‘60s band Steppenwolf, and of Rory Block. And then to hear them speak, in separate sessions, about their careers. Kay had a fine anecdote about defeating the local censors in Virginia during a performance of “The Pusher.” Block, as a teen-ager growing up in Greenwich Village, had met bluesmen like Son House, Mississippi John Hurt and the Rev. Gary Davis. But her slide playing took on new dimensions when, a few years later, she paid close attention to Bonnie Raitt. May the circle forever be unbroken.

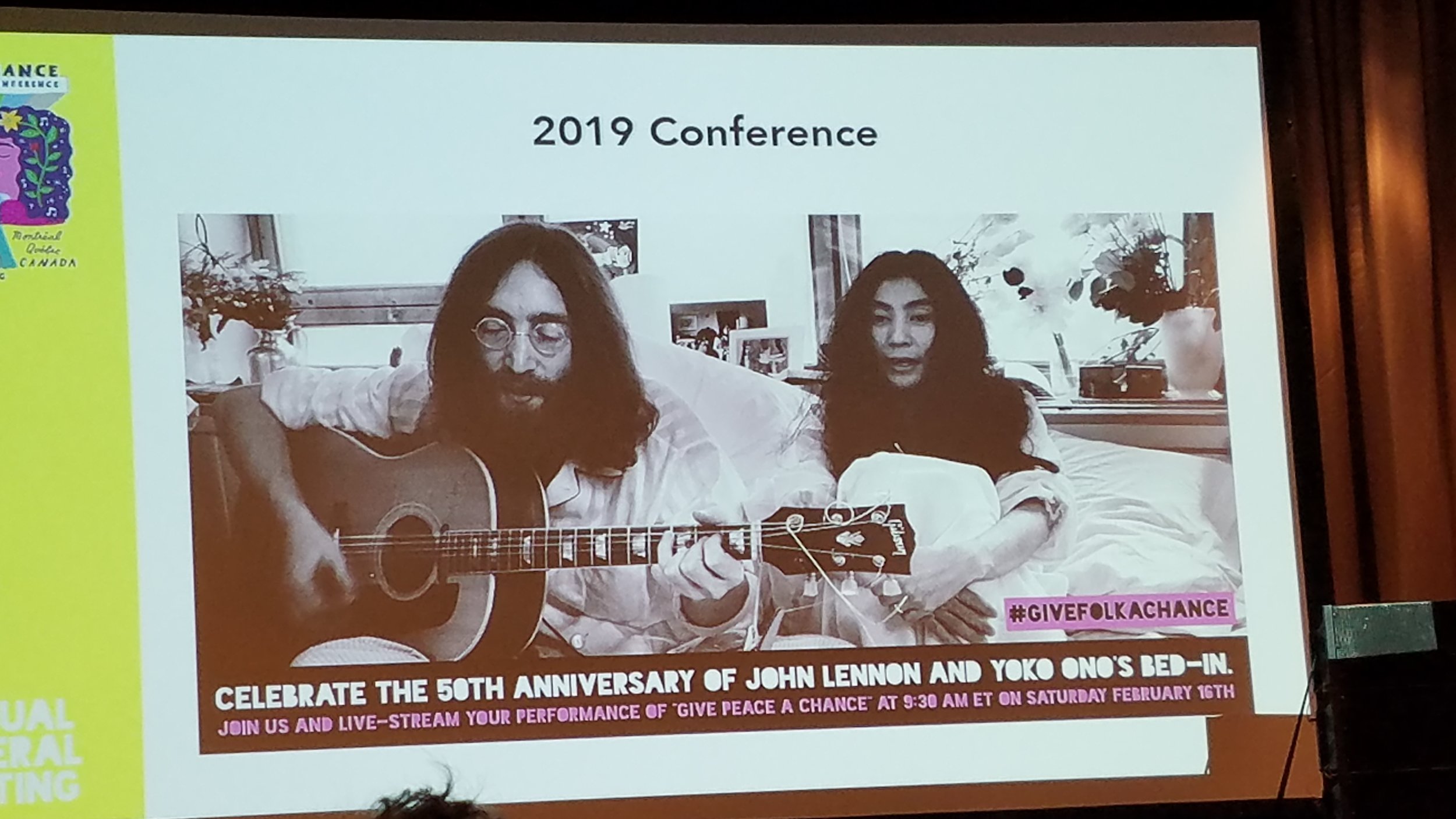

A few more prominent spirits hovered over the long weekend. Foremost was Leonard Cohen, who hailed from Montreal. But also: John Lennon and Yoko Ono, whose give-peace-a-chance “bed-in” was commemorated 50 years to the day later – and in the very same hotel.

The Folk Alliance conference moves on next year to New Orleans then takes up residence again in Kansas City, the organization’s world headquarters, in 2021 and 2022. You can bet I’ll be there, ears and heart wide open.

Gallery photo captions (from left): Jenna Mammina & Rolf Sturm, Leonard Cohen, Sam Lynch, Emerald Rae, Marc Berger, Danny Schmidt, Alice Howe and Freebo, John and Yoko bed-in promo, Rory Block, John Kay, Arctic Song, Eric Andersen, Calvin Arsenia jam, Mireya Ramos, Flor de Toloache, Jim Lauderdale, Livingston Taylor, Adrian Sutherland, Beausolais with Michael Doucet, Alash Ensemble, Eliza Gilkyson, Montreal and Los Angeles guitar trios, Maya de Vitry, Black Horse Motel, Melanie Brulée (with cellist Desiree Haney of Black Horse Motel).