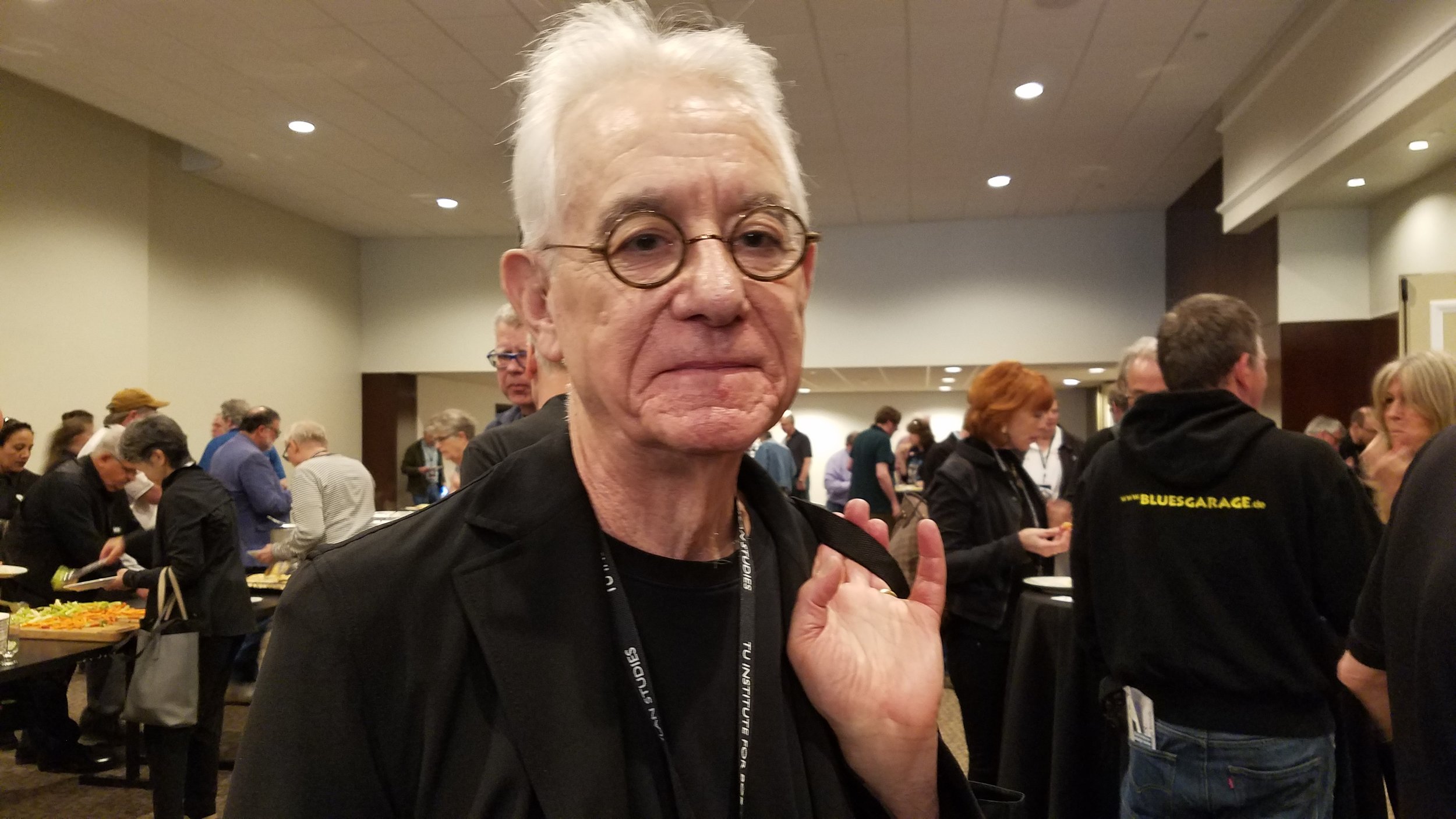

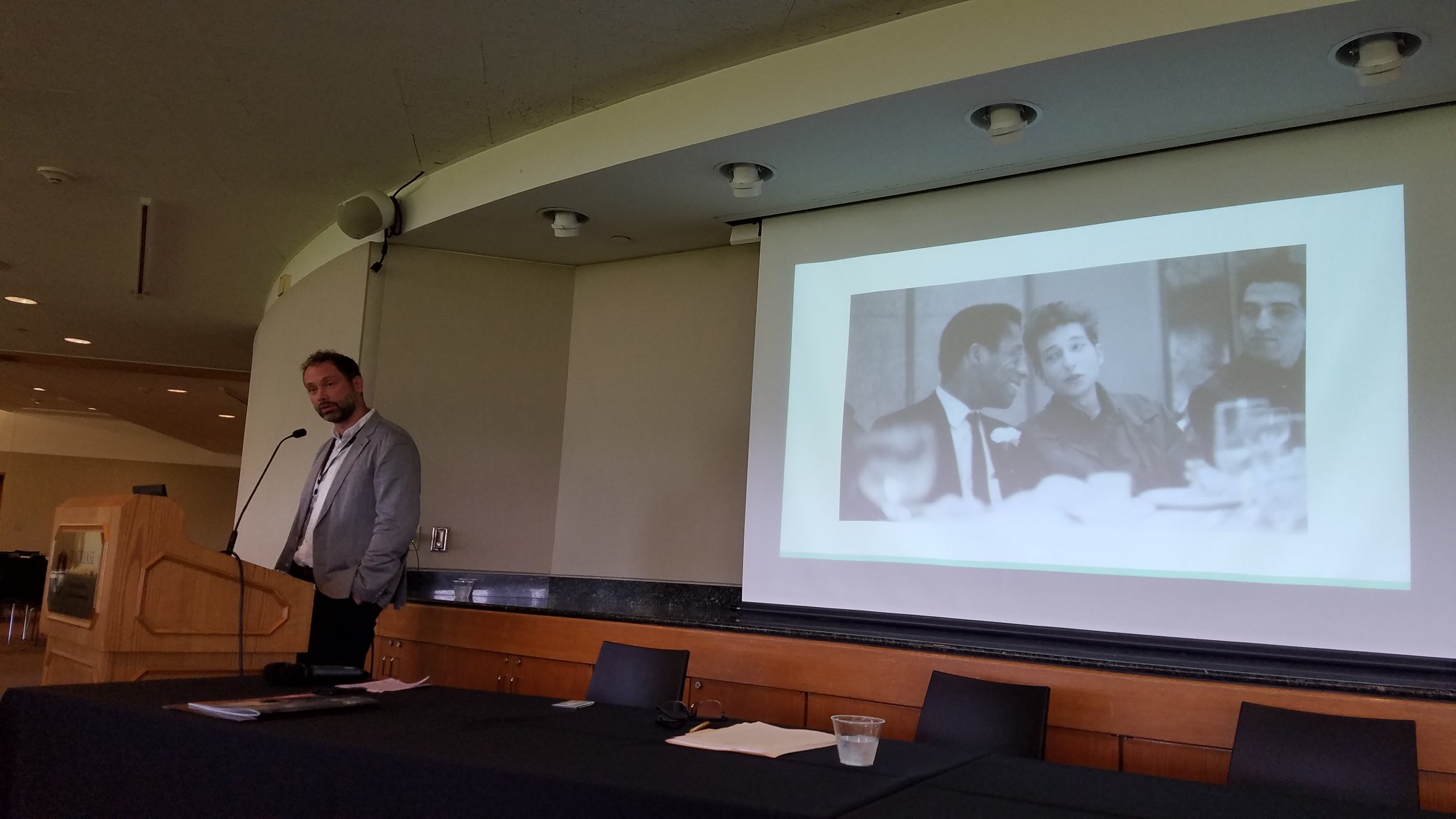

The World of Bob Dylan (photos above, from left): A conference poster; keynote speaker Greil Marcus; exhibits at the Gilcrease Museum include visual art works (drawings, portraits, sketches) by Dylan, and “Shakespeare’s in the Alley,” an installation of hand-lettered banners of Dylan lyrics by Skye, a Minnesota artist; Jeff Fallis, of Georgia Tech, delivers a paper on Dylan and James Baldwin; the writer Robert Polito discusses the Bob Dylan Archives with Michael Chaiken, curator of the collection; music critic Ann Powers; Laura Tenschert, a panelist and host of a London radio show on Dylan; panelist Nicolette Rohr on “Them Screamin’ Girls”; Roger McGuinn.

By Steve Paul

(c) 2019

Ninety minutes of rare concert footage. Deeply researched scholarly papers on poetry, art, song-making and mystery. Non-stop chatter on the nature of Bobness. This was the World of Bob Dylan, a symposium in Tulsa into which I immersed myself for the better part of four days.

Why? Because. Why Tulsa? Good question, but easy answer: A few years ago a broad-minded and very wealthy local foundation acquired Bob Dylan’s voluminous archives (manuscripts, photographs, recordings, etc.) and arranged a partnership with a handful of institutions to preserve them and make them accessible to serious researchers and, eventually, to the public in the form of an exhibition center still on the drawing boards.

So Tulsa, already the home of the attractive and important Woody Guthrie Center, with its public exhibitions and researchable archives, now is fast becoming the center of the Bob Dylan world, or at least that part of the world, populated by grey-bearded scholars and completist acolytes, that leads one to spend every waking hour in the mist of Dylan’s music and contemplating his vast myths and mysteries.

For as long as I’ve been listening to Dylan -- more than half a century, that is -- it was sobering to discover how little I really knew about him. He has been famously slippery about his life, creative consciousness and working methods except as they might be revealed (or not) in his work. He has been an artist of many guises — folk singer, poet-prophet, rock star, recluse, spiritual seeker, crooner, and, now, protector of his own enterprise as artist, song-writer and non-stop, touring performer. As much as I tuned my ears to his greater periods, and the formative cultural moments that helped to shape my own way of being and listening, over the years I drifted on and off of Dylan’s trail, so my grasp on the details remained tenuous at best.

So here I was surrounded by experts and obsessives who could itemize every time he altered a lyric or tell you which woman Dylan may have been singing about in this song or that or had seen him in concert, say, 67 times in the last 20 years or had thoughts about what he meant when he sang “How do you feel…?” There was the fund manager and harmonica player who could rattle off every recording on which Dylan picked up a mouth harp and how he played it. Or the young London woman, Laura Tenschert, who produces a radio show on Dylan and argues quite rightly that, first, how we think about Dylan has largely been shaped by generations of white male critics, and, second, we need to hear more from women and people of color on his work, influence and legacy.

As it happened, and not so unexpectedly, the audience for these proceedings was near totally white and predominantly male. Still, it was gratifying to hear young female Ph.D. candidates offering important takes on Dylan studies. One explored the Nobel laureate’s literary romanticism (see Emerson and Rimbaud). Another looked into pop-cultural myths about “screaming young women” and gender bias in the realm of music fandom in the 1960s. Regretfully, I missed a panel of three papers on Dylan and Native American trickster tales and discussions of the mostly overlooked role played by female African-American singers in Dylan’s gospel-influenced period of the 1980s. A presentation on Dylan and James Baldwin, who intersected once at a public event in New York, drew illuminating parallels between their respective voices in the civil rights movement, circa 1963.

Among the best-known presenters, the deep-think pop critic Greil Marcus discussed Dylan in the context of the blues. Dylan drew from that distinctly African-American source material for the album that announced his arrival as a folk singer in 1962, and 30 years later he returned to it in a haunting, evolutionary way on “Time Out of Mind.” The NPR music critic Ann Powers traced Dylan’s long career of myth-making and trend-setting through a series of self-conscious changes in his bodily image that, she maintained, reflected social movements, lifestyle upheavals and gender fluidity in the music world and beyond.

Roger McGuinn, the guitarist and co-founder of the Byrds, didn’t reveal much of substance about Dylan per se – did you know he was quite a skier? -- when he took the stage on the last conference night to talk about his own career and sing a few tunes. McGuinn’s association with Dylan dates to early 1965, when his band recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The Byrds’ version of the song became the first Dylan-written pop hit and usually is credited with jump-starting the folk-rock sound. McGuinn played on the Dylan soundtrack for the movie “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” (1973). And two years later, Dylan recruited McGuinn to join the Rolling Thunder Revue (see the new Martin Scorcese docu-fantasy of that 1975 tour, now gloriously streaming on Netflix). “It was,” he said, “the best two-month party I’d ever been to.”

The Tulsa conference lasted only four days, and it hardly generated the carnival atmosphere that Dylan spun for Rolling Thunder. But, for me at least, it laid the groundwork for much further exploration and for living more deeply with Dylan and his music.