This essay, which I wrote before the publication of Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, appears as part of a package about me and Connell in an online feature of New Letters magazine: https://www.newletters.org/digital_features/steve-paul-spring-2022/

By STEVE PAUL

Evan S. Connell, the writer largely known for his portrayals of domestic uneasiness in mid-20th century America, never shied from the realities of whiteness and race.

His two novels about a prosperous Kansas City family in the 1930s and ‘40s, Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge, contain numerous incidents that peel back the scab of genteel indifference and overt scorn that white Americans brought to race relations.

Connell wrote Mrs. Bridge in the 1950s, in the era when the civil rights movement and conflicts over the grip of Jim Crow segregation were both growing. Mr. Bridge followed 10 years later, in 1969, following the legislative successes of the 1960s as well as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., John Kennedy and his brother Robert, and Malcolm X.

But both novels looked back to an earlier period, one at least partly reflecting Connell’s own boyhood in Kansas City. He was born there in 1924, left for college and the Naval Air Corps in the early 1940s, and essentially left for good, via the G.I. Bill and a wandering spirit, a few years after the end of World War II.

While some readers might be aware of Kansas City’s status as a “wide-open” playground, a sin city that was fertile ground for the blossoming of the sound of jazz, the realities of systemic segregation and cultural racism were no less in force than anywhere else.

In Connell’s novels, a reader’s sense of the state of race relations in Kansas City in that period often comes through the Bridge family’s interactions with their Black housemaid and cook, Harriet. (Emblematic of Harriet’s diminished stature is the fact that it’s not until late in the second novel, do we learn her last name, Rodgers.) She had served them well for nine years and even loyally rebuffed another matron’s offer of $10 more to leave the Bridges and work for her.

Another foil in Mrs. Bridge is Alice Jones, daughter of a neighbor’s “colored gardener,” whose developing friendship with one of the Bridge daughters is essentially snuffed out.

We are meant to consider how India Bridge, the novel’s timid matriarch, welcomed daughter Carolyn’s attitude toward the Black girl, how she thought that Carolyn saw no difference between them.

Yet, Connell leaves the reader with the truer insight: "Soon, she knew, the girls would drift apart. Time would take care of the situation."

In fact, “the situation” lingers in numerous ways throughout both books.

Mrs. Bridge once had to instruct Carolyn not to refer to the maid as a “cleaning lady”: “You should say the cleaning ‘woman.’ A lady is someone like Mrs. Arlen or Mrs. Montgomery.” [22]

And she was full of subtle discouragements and slights, intentional as well as unconscious, regarding Alice. The end came when Mrs. Bridge counseled her daughter against accepting an invitation to a party at Alice’s house. Alice lived at Thirteenth and Prospect, “a mixed neighborhood.” “Can I go?” Carolyn asked. “I wouldn’t if I were you.” [41] Connell gives the episode another look in Mr. Bridge. Later in the day, India Bridge mentions the party invitation to her husband and wonders whether she should say it would be OK to go. “I don’t want Carolyn to get in the habit of visiting that end of town,” Walter replies. “Carolyn doesn’t belong at Thirteenth and Prospect any more than you or I do. Those people resent us.” [MrB 78] It never occurs to either India or Walter Bridge where that resentment might come from.

Late in the first novel, the Bridges hire a chauffeur, an “affable colored man” originally from New Orleans. The arrangement fizzled after a few weeks, when phone calls from the man’s creditors proved to be overly annoying. Subsequent experiences with two Asians and another Black man soured Mrs. Bridge and her husband on the idea of having a driver after all.

Some years later, after Carolyn is married and living in a Kansas suburb, she visits her mother and mentions she and her husband were talking about buying a house, one with a decent yard and a dry basement. Carolyn now was very much conscious of “the situation.” She tells her mother of a concern about a neighborhood they’d looked at: “The niggers are moving in.” [235] Mrs. Bridge did not know how to respond. She reflected that “she herself would not care to live next door to a houseful of Negroes; on the other hand, there was no reason not to. She had always liked the colored people she had known.” Well, of course she had.

Mrs. Bridge does tell Carolyn that surprisingly she had run into Alice one day in a downtown elevator. It had been years. Alice now worked as a hotel maid, and Mrs. Bridge noticed how she looked darker—“so black”—than when the two girls played together. “It’s such a shame.”[236]

In four simple words, Connell thus exposes not only the shame but the tragedy of white privilege and the enduring pain of the “all-American skin game,” as the late Stanley Crouch once put it, albeit in a somewhat different context. Carolyn suggests there’d be no reason for her to visit Alice. She wouldn’t know what to say.

As Connell returned to the family portrait a decade later in Mr. Bridge, the subject of race becomes even sharper. American cities, including Kansas City, had been burning, and the toxic atmosphere couldn’t help but inform Connell’s vision as he reflected on a societal landscape of two or three decades earlier.

It’s likely that Connell was also stirred by an increased understanding of the disturbing racial picture emanating from his old home town.

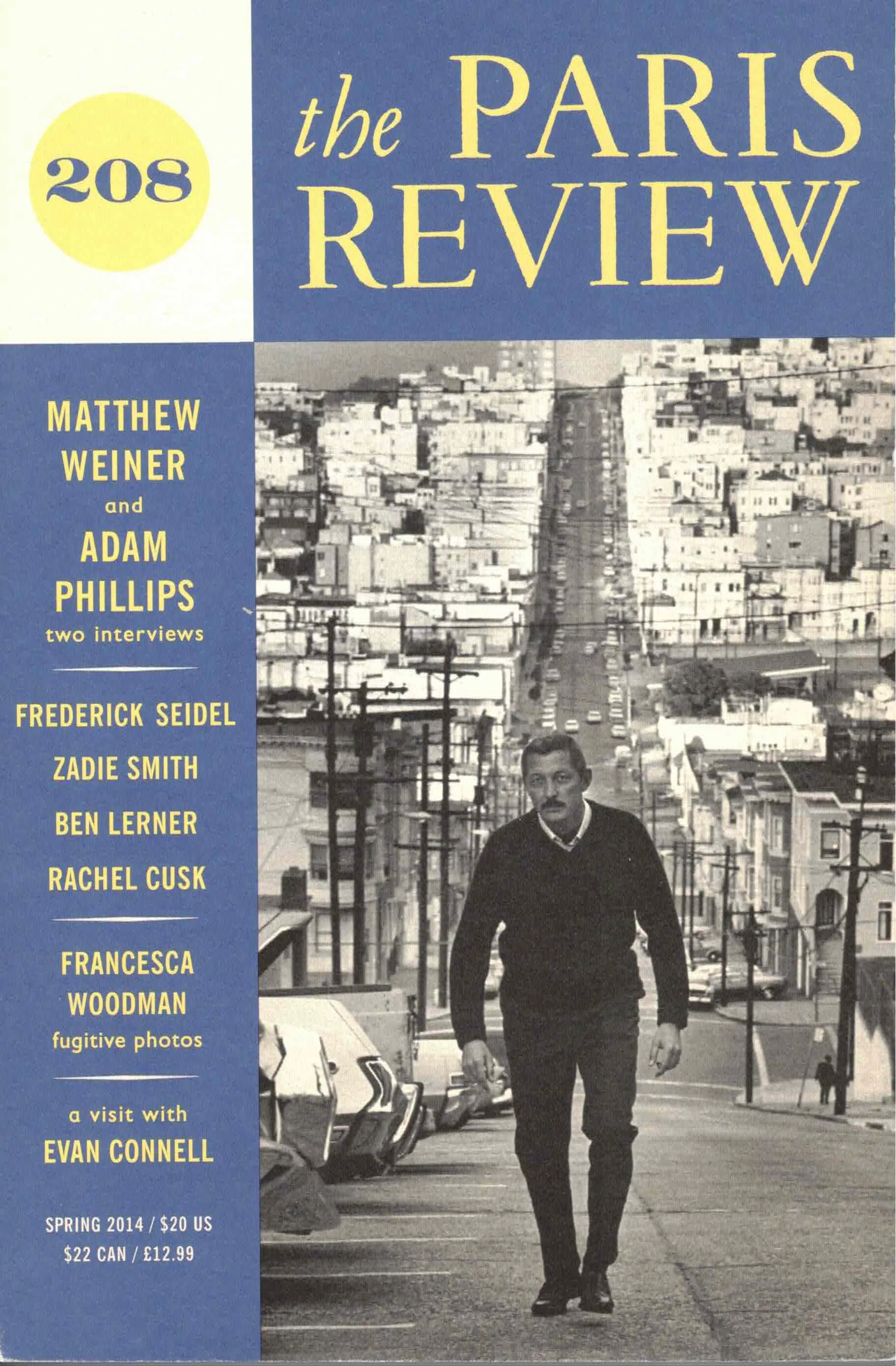

By the early 1960s, Connell, while living in San Francisco, had attached himself to a literary magazine, Contact, published across the bay in Sausalito. Connell became a co-editor and some of his work had appeared in the journal in recent years, including segments from Mrs. Bridge several months before its arrival as a novel.

In 1963, Connell produced an editorial comment—it was unsigned, but I’m certain of his authorship—about a Kansas City, Kansas, family who were snared in a web of injustice and tried to do something about it. The Shanks family refused to send their children to a segregated school, were not allowed to send them to a white school, and were fined when they chose to teach them at home. This was a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education, which called for the end of school segregation. That federal case, of course, had arisen from Topeka, just an hour west. The editorial not only lamented the situation and lauded the Shankses quiet heroism, but took the local media to task for their hypocrisy and, in the case of the Kansas City Star, shameful silence.

As the portrait of Walter Bridge emerged from his consciousness, Connell was unsparing about the family patriarch’s hardly suppressed racist attitudes.

One of the most quietly searing moments in Mr. Bridge occurs after India Bridge sees a photograph from a lynching in a news magazine. As we know from many such photos, the dangling Black victim was surrounded by a crowd of grinning, leering white men and boys. “What on earth makes people behave that way?” she wants to know. Her husband takes in the scene, feels the violence and the setting in a sensory, knowing way, and exclaims that most disappointing of equivocations: “There are many fine people in the South.” Then he blames the victim, figuring he must have been doing something “that he shouldn’t have been doing.” Hell, Walter Bridge says, he’d spent a few days in Atlanta once, “and I never met more courteous people.” [78-79]

Scenes with Harriet Rodgers again present opportunities to reveal Mr. Bridge’s character. When some coins go missing from his dresser, he can’t help but wonder if she, rather any of the children, stole them, because there was no proof otherwise. When Carolyn and Harriet have a little spat, however, he blames his daughter and warns her to treat the maid with dignity and to remember Lincoln’s words: “It is no pleasure to me to triumph over anyone.” [102]

When Harriet informs Mr. Bridge that her nephew in Cleveland had received a four-year college scholarship and wanted to go to Harvard, he takes it in skeptically. Later, to his wife, he fumes: “No good will come of it.”[178] When a boyfriend gets Harriet in trouble with the police, Walter drives downtown to pick her up and warns her that there’ll be no more of that.

After the oldest Bridge daughter, Ruth, moves to New York, her father pays a visit on a business trip. He meets a Black friend of hers as they wander through the Metropolitan Museum. He wonders how often Ruth and the friend get together, and Connell channels his insecurity, which, of course, remains the insecurity of much of white America: “Perhaps this intermingling of the races was inevitable. In centuries to come it might be all right. But not now.” In my reckoning, the line can’t fail to prompt a response, coined by an ancient rabbi: “If not now, when?”

Connell well knew that he was pulling back the curtain on uncomfortable matters. As Mr. Bridge was undergoing proofing and revisions, he added a couple of vignettes to heighten the racial undertones. In one, he wonders about a series of attacks on neighbors’ dogs in the form of ground beef laced with bits of glass. He suspects the perpetrator must be one of the Black laborers in the neighborhood.

Connell’s own father, a noted eye surgeon in Kansas City, was known for his stern, businesslike, and distant demeanor. Connell conceded that his father at least in part inspired Walter Bridge and his attitudes—about Jews as well as Blacks.

Depictions of everyday racism arise only sparingly elsewhere in Connell’s body of work. The scope of his vision, however, in nearly 20 distinct books spanned the clash of civilizations and the vast human record of folly, intolerance, suffering, and violence. Rather than period pieces of a quaint and quiet America, his two Bridge novels retain, for better and worse, some timeless and contemporary power.