More than 14 years ago I spent a bit of reporting time following around the artist Laura DeAngelis, who was in the midst of creating a large public-art project in the heart of downtown Kansas City. She was a ceramicist, a visionary, a birder, and a gentle soul, who, if I recall correctly, also was an accomplished barista at Broadway Coffee in Westport. Well, those who knew Laura were saddened and shaken to learn this spring that she had died. Apparently, amid a mental-health crisis, she’d taken her own life. Laura had left Kansas City many years ago, and I’d had no contact with her, pretty much since I wrote this long magazine piece for The Kansas City Star Magazine. It appeared Jan. 20, 2008 under the headline “An Idea Takes Flight.” One corrective: When I dug out the story, I was horrified to learn that I’d committed a little crime against journalism: For some reason I can’t recall, Laura’s name appeared with a space in it (De Angelis) throughout the story. Mea culpa and apologies to Laura’s legacy and her family and friends. I’ve fixed that here. And another note: Not mentioned in the story, because Laura asked me to keep it out, was the presence in her apartment, in addition to her canary named Victor, of a crow she had rescued. She feared the wildlife authorities would not approve. I recently stopped by Oppenstein Park to gauge the current state of the installation, 14 years after its dedication. The park—property, I think, of Jackson County rather than the city—seems a little forlorn. And it’s hard to imagine that the mechanical star map still works (please correct me if you know otherwise). But it is nice to see that signage about Laura’s project as well as her metal bird medallions and lovely ceramic tiles remain in place.

By STEVE PAUL

Laura DeAngelis is bundled up against a wind whipped morning chill. She wears a brown quilted jacket and tan denim pants. A work crew is laying a bed of concrete in a vest-pocket park downtown, and DeAngelis, an artist, is about to make a gesture that’s the biggest of her short career.

She kneels down on pads atop the quickly firming concrete. She bends over and places a steel emblem of a bird—a finely detailed kingfisher with a berry in its beak onto the pavement-to-be.

Soon one of the workers, Mike Ward, takes over, further pressing the bird into the stiffening gray goo. He starts to clean the edges. It’s a fine bit of troweling and trimming that he keeps up for the next 30 minutes.

Fourteen more of the artist’s birds eventually will end up in the concrete. A wren, a green heron, a yellow-billed cuckoo. And that’s only the beginning of the transformation of Oppenstein Brothers Memorial Park.

The centerpiece of the redesigned park will be a 10-foot wide interactive map of the stars set on a base tiled in intricately carved ceramics, also from De Angelis’ hands.

At 12th and Walnut streets, the 7,000 square-foot- patch of urban calm has long been a symbol of civic renaissance—and failure.

Once described in this newspaper as a place where even the pigeons wouldn’t stick around, Oppenstein is on the verge of becoming the little park that could.

DeAngelis, along with a t3m of designers, planners, builders, bureaucrats and boosters, has been working for more than a year to make that happen.

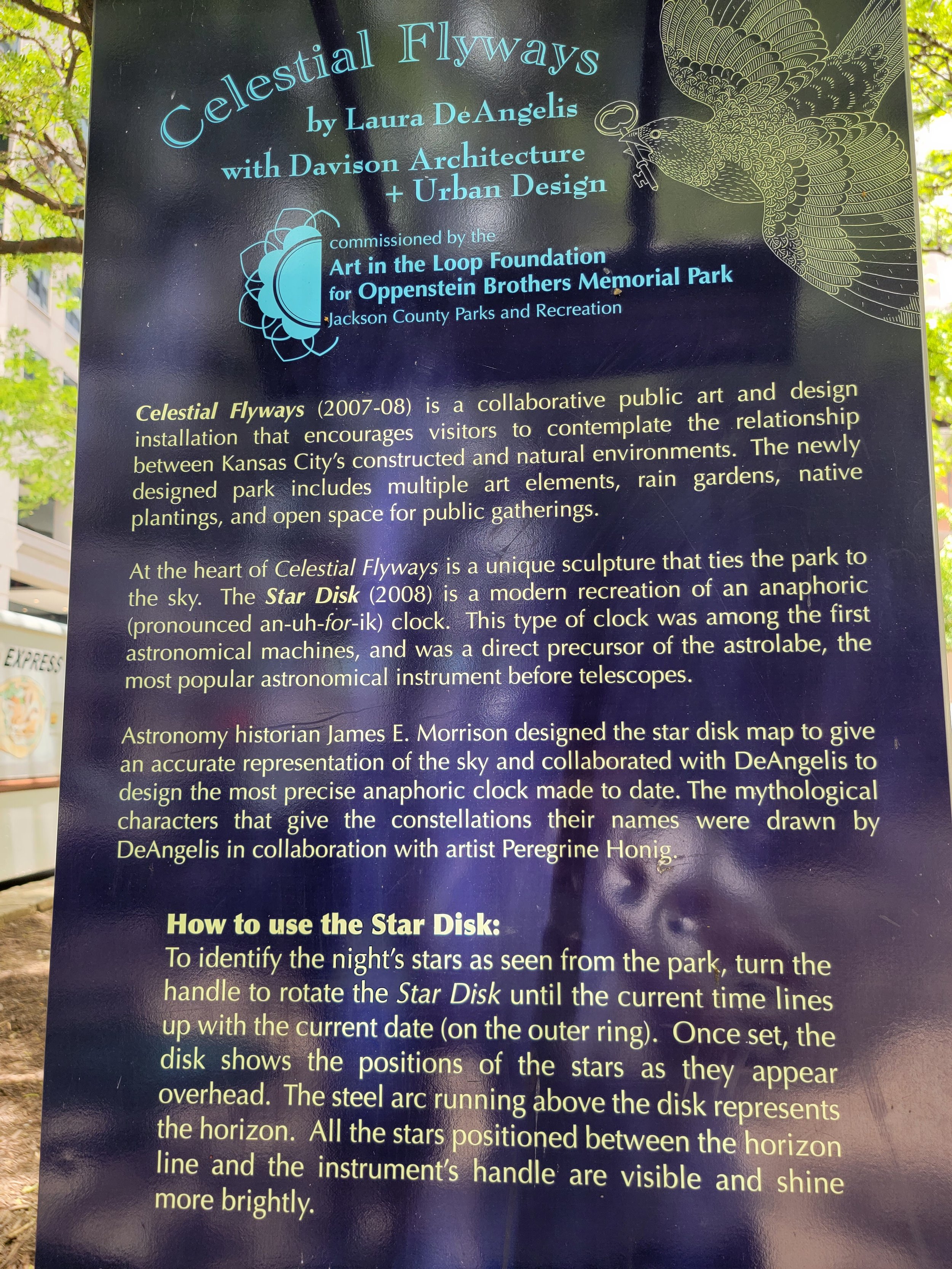

The story of DeAngelis’ public art project, called “Celestial Flyways,” illustrates the complications that accompany the transformation of public space. But it also shows how a single artist can expand her creative vision, help forge a piece of civic identity and, despite the bureaucratic wringer that defines so much of the process, maintain her passion.

“I don’t think I had any idea how many aspects you had to deal with to make a public art project in comparison to being a studio artist,” DeAngelis says. “It makes you practice some good time-management skills. It makes you think that things should happen so much easier than they do.”

As a new graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute in 1995, Laura DeAngelis did her part to blaze the urban frontier. She spent four years transforming a third-floor industrial space on the northeast edge of downtown into a light-filled, high-ceilinged home and studio.

“I didn’t make a single piece of art,” DeAngelis, now 34, says of that renovation period.

Small teapots now line the top of a door frame. Ceramic tiles she designed cover the bathroom floor and walls. Her canary, Victor, chirps loudly in the sunny living room.

As an artist, DeAngelis frequently turns to the past for inspiration. The large ceramic, figural sculptures she has shown in recent years with great success, appear as if they stepped out of Renaissance canvases.

A few years ago, as she thought aobut applying for a public art project, she began wondering about the astrolabe. That ancient instrument helped astronomers reconcile time with the positions of the sun and stars in the sky. The astrolabe was a computer of its day—or, more properly, a slide rule, given its manual operation.

DeAngelis had encountered astrolables as a child at the Adler Planetarium in her native Chicago, which has one of the world’s largest collections.

“I’ve always loved old instruments,” she says. “They looked mysterious.”

While researching her project she found James E. Morrison, a retired computer engineer in Delaware, who had created a Web site devoted to the astrolable.

Seeing the chance to bring the wonders of the old tool to a wide audience, Morrison offered to collaborate with DeAngelis on her project. They soon decided it would be more practical to create a simpler device called an anaphoric clock.

A precursor to the astrolabe, dating back some 2,000 years, the anaphoric clock polots the sky and the passage of time but with fewer moving parts. That would make it more practice for a public, interactive installation, which here will mean a hand-cranked mechanism to align the date and time with the stars above the park.

“This will be by far the biggest anaphoric clock that’s ever been made,” Morrison says.

Morrison and DeAngelis e-mailed ideas and images back and forth. Morrison was impressed by his new astronomy student.

“She’s learned very quickly,” he says.

DeAngelis first proposed a public art project, including an anaphoric clock, at another down site, but it didn’t fly. When the Art in the Loop program sought proposals to re-energize Oppenstein Park, she was encouraged to try again.

As she studied the park, DeAngelis knew she wanted to connect people to the stars andto inject a sense of nature into the city.

“I’m in this very urban place, but I really love the country. I was thinking about all the things I love about the country and how I could bring it into the city.”

She was fond of running her dog along the riverfront, where, as a bird watcher, she took note of all the avian visitors who pass through mostly unnoticed. Scissor-tailed flycatchers, hooded mergansers—these are impressive travelers. “If you’re not looking for them, you don’t see them.”

DeAngelis also knew that to make a real impact on Oppenstein Park, she needed to come up with something more than a piece of so-called plop art.

“I started thinking not just about an art piece, but engaging people and getting them to stay in the park.

“Putting a sculpture in the park was not going to be enough.”

Encouraged by Art in the Loop to create a team of designers and engineers, DeAngelis selected Dominique Davison. Davison had recently established an architecture and urban planning firm in Kansas City with her husband, Robert Riccardi, after working for top architect Cesar Pelli out of New Haven, Conn.

Their plan evolved into a makeover of the park.

Davison proposed new landscaping, concrete planters and benches, and she worked with DeAngelis on aspects of the bird pieces and the placement and design of the star disc. The metal disc with include 496 holes, pugged with acrylic lenses, lighted from below. Visitors will set the current time and date, and the disc will replicate the stars above that very spot.

The disc will also have 50 constellation drawings by DeAngelis and Peregrine Honig etched into the surface.

In addition to the large tiles cladding the star disc wall, DeAngelis also designed a suite of smaller ceramics that will line the risers of three wide stairs. Those pieces will join the birds already set in the paving along with arced grooves in the concrete representing their migratory patterns.

The project won the Art in the Loop competition in October 2006 but, as these things go, rather than hunker down in her studio to produce the drawings and tiles, DeAngelis found herself sucked into the sort of process that rarely looks like art. Meetings and more meetings. For months.

A year ago, she and Davison and two dozen other people sat in a workshop downtown for parts of two days exploring the issues of public space. Consultants from the Project for Public Spaces in New York guided the locals through exercises on designing effective parts and plazas.

Among the participants was Bill Dietrich, executive director of the Downtown Council. When he arrived a few years ago to kick-start the council’s Community Improvement District, one of the top items on his to-do list was cleaning up Oppenstein Park.

Sprint Center was rising around the corner, H&R Block was moving into its new building a block away and the Power & Light District was coming out of the ground. With every sign of surrounding progress the park had become more central and more attractive as an urban experiment.

Dietrich, along with Art in the Loop’s Kate Hackman, gathered people who saw the need to improve the park not just for aesthetic reasons but also for a shared vision of community. County parks people and neighboring property owners found common ground.

“That’s new concept downtown: ‘Investing in public space enhances the value of my property,’ “ Dietrich said at the time.

After the workshops came months of working out details and solving technical problems of producing the metal birds and the star disc from DeAngelis’ detail drawings. The total budget—including the art works, site demolition and deconstruction, surveys, permits, contractor fees, signage, insurance—eventually was set at $475,000.

Meanwhile, DeAngelis tested ceramic ingredients and glazes. And she calculated every-shifting dimensions for the tiles she planned to carve, a mathematical process made more complicated by the curvature of the star disc base and the 13 percent shrinkage her pieces would undergo in the kiln.

Over the summer DeAngelis got a chance to extend her bird emblems beyond the park. The early arrival, a bird with a key in its mouth, got pressed into a new sidewalk across the street, on the southeast corner of 12th and Walnut.

One day she and her fiancé, Louis Rose, went to see it.

“it was covered in dust,” she remembers. “Louis spit on it to clean it up, and a security guard comes over and asks, ‘Why are hyou messing with the pigeon?’ “

“So we can see it better,” Rose replied.

DeAngelis was happy that the guard was protective of her artwork, but what she really wanted to say was, “It’s not a pigeon, it’s a rose-breasted grosbeak.

A few weeks ago DeAngelis stayed up all night to finish building a full-scale, quarter-section mockup of the star disc installation.

All of her birds had been pressed into the park’s new paving. A new planter wall and concrete benches were in place. Many of the tiles she had labored over with carving tools and a gentle touch had been fired and were awaiting placement on the site.

Installation of the star disc, which is being fabricated A. Zahner and Co., and most plantings will wait till late winter and a planned March reopening of the park.

For now, the mockup wedge sat in her living room as Art in the Loop board members, county parks peoples and other visitors got to see up close what the finished centerpiece would look like.

DeAngelis had even covered the low curved wall with plaster modls of the large tiles in progress, which include her stylized Missouri water lilies and curling, watery waves.

“This is going to be a lot more dramatic than I realized,” says David Miles, president of the H&R Block Foundation and board member of Art in the Loop.

Jonathan Kemper, of Commerce Bank, peppered DeAngelis with questions about the mechanics and materials of the star disc, the interior lighting and other aspects of the plan.

“This is cool,” Kemper says. “The color is fantastic.”

DeAngelis explains to Porter Arneill, director of the Municipal Art Commission, how she has put in hundreds of hours carving just the two largest tile, which she molded and repeated to make a total of 36.

Arneill notes how the public rarely understands how much work goes into these kinds of projects.

“We know more about how people make barbecue,” he says, “than we do about how all these artists make art.”

Victor, the canary, sings in the background.