The Kansas City Star’s Judy Thomas wrote this week about the death of Leonard Zeskind, a Kansas Citian committed to researching and uncovering the many tendrils of white nationalism in the U.S. His landmark book on the project was one of hundreds recently purged from the library at the U.S. Naval Academy by the reckless administration, Judy reported. In 2009, I wrote about the book upon its release, and reading about it again, in this fraught moment of authoritarian and right-wing fervor, speaks to its utter timeliness and timelessness. In visits with Zeskind at his office at the time, a labyrinthine lair lined with file cabinets, he displayed both a sly sense of humor and utter seriousness about his work. In one moment, he beseeched me to aim a bottle of lubricant into his eyes. That was a first in my newspaper career. The story below first appeared on page 1 of The Kansas City Star on May 18, 2009.

kansas city

From the Archives: That Time Gillian Flynn Tried to Kill Me

With Gillian Flynn, the Gone Girl goddess, coming back to her hometown soon, why not flash back to the feature profile I put together in 2012. At the time, Flynn’s writing career and personal life had begun to soar. She graciously allowed me to visit with her in her Chicago home and to follow along as she appeared at a bookstore reading. That’s when it got really interesting—though I left this little detail out of my magazine piece. (Why oh why? It shoulda been the lede, maybe?) I was a passenger in Flynn’s car as we returned to her place from the suburban bookstore. At one busy intersection, she made a left turn…INTO THE WRONG, ONCOMING LANE, if I recall correctly. It didn’t take long to correct the driving error, but still. We joked about how maybe she was having the impulse to bump off this nosy writer. Whatever. Maybe she tells the story differently. Maybe she doesn’t even remember it. Although we shared a stage once in an event for the Mid-Continent Library, we’ve had little to no contact ever since. It certainly has been fun to follow her projects over the years, and nice to hear that she’s struggling to work on another novel. In any case, I’m sharing here the magazine pages of that story, published just about a dozen years ago, Nov. 12, 2012, in The Kansas City Star Magazine (remember when?). Some of the photographs are mine; I was happy to line us up with my friend Emily Railsback, who had recently resettled in Chicago, to shoot the cover portrait.

Baseball and KC's Crossroads? Can't We Devise a Better Plan?

A belated posting from earlier this year on the eve of the crucial vote that put a stop to the building of a baseball stadium in Kansas City’s arts district. For now. I think the ideas still hold. We’re still waiting for Plan B. The piece first appeared online at kcstudio.org

In the gallery above, scens both inside and outside the footprint of the proposed Royals stadium in the Crossroads Arts District.

By STEVE PAUL

(c) 2024, Steve Paul

Is it possible to be both a baseball fan and against the Kansas City Royals’ proposal to build a downtown park in the Crossroads Arts District? Well, why yes it is.

I went to the season-opening game on Thursday, not necessarily out of loyalty to the Royals but because a friend was in from out of town and wanted to go. As we sat there in the sunny upper deck, amid a sold-out crowd, the team largely displayed its all-too-frequent, uninspiring ways. (There’s hope for the team’s new starting pitchers and anxiety over a continued lack of offense and ineffective bullpen.)

But what I also thought about the enormous waste—economic and ecological—that would occur if Kauffman Stadium were imploded and scraped away, largely for the benefit of the football team that has shared the Truman Sports Complex for half a century.

Other than that, I’m not really opposed to further invigorating downtown with a baseball park. Nevertheless, like most of the people I know who have made the Crossroads synonymous with creative culture in Kansas City, I am opposed to the proposed location. Scraping and replacing the Kansas City Star’s modern printing plant (vintage 2006) seems like another waste, though one might empathize with the owners of the white (green) elephant who must’ve known they were taking a risk when they bought it and haven’t yet thought of anything else to occupy what could yet be a landmark building downtown.

I certainly understand some of the economic synergies that might occur. Foremost are the potentially lugubrious connections that this ballpark would make with the existing Power & Light “entertainment district” and the T-Mobile Center by way of the South Loop Park, which is envisioned to cap the highway in between it all. Perhaps this would alleviate some of the extra pressure that undoubtedly would occur in the neighboring blocks and businesses in and outside the ballpark’s proposed footprint. I’m hearing that one of the main beneficiaries of this vision would be the Cordish Cos., developer of Power & Light and the adjacent luxury high-rises, all of which are subsidized by an approximate $14 million annual contribution by the city (hello, taxpayers). But Cordish and their city protectors should not be calling the shots here.

Well, it should be no surprise to anyone who knows me—and this is not about me—that I am in solidarity with most of my artist and hospitality and Crossroads friends in standing against this big idea. A Crossroads baseball stadium wouldn’t necessarily destroy the neighborhood, but it would change it irrevocably. Which is why—this took a while to get here in real time—I’ll be voting no on extending the sports-sustaining three-eighths cents sales tax on Tuesday.

I’m not a sentimentalist, and I’m not opposed to change. I spent something like 45 years in the historic Kansas City Star building, which would still stand across 17th Street to the south of the stadium site, assuming its long-overdue redevelopment gets back on track and succeeds. My last office in the building directly overlooked the Brick across McGee Street, the quirky and lovely bar, grill and edgy music venue that will surely suffer during construction and after the neighborhood aura transforms to something that will probably be incompatible. OK, this is maybe sentimental: The Brick still serves burgers in the style of menu staples of its predecessor, The Pub, in the 1970s.

But why disrupt the clearly successful and organic growth of the creative-oriented Crossroads with a gargantuan, big-footed intruder from the world of sports. Next we’ll see an influx of betting parlors, right?

In the run-up to this late-breaking and ham-handed reveal of the Crossroads plan, the Royals led us to believe that they were seriously considering two other locations. One was in a largely industrial stretch of North Kansas City, and, frankly, people, I didn’t think this was as far-fetched of an option as it appeared. I mean, the site would have been in view of downtown and just across the Missouri River, and maybe we’d get water taxis or another bridge to go along with it.

The other site, the East Village, would’ve filled in a rather barren area northeast of City Hall and adjacent to the headquarters of J.E. Dunn, the contracting firm that, lo and behold, would probably build the stadium wherever it might go. Small town!

It’s clear that the Royals ownership was convinced—cajoled? hoodwinked?—into thinking that the East Village option would be more expensive than the Crossroads option, because with the latter they wouldn’t have to follow through with their promise to wrap in a new entertainment district surrounding a new stadium.

Granted, the East Village would be several more blocks away from Power & Light, and a new “entertainment district” might cannibalize the existing, tax-supported playground.

But I tend to operate in a mode of wishful-thinking idealism, and I can’t help but suggest that urban planning and architectural visionaries might be able to devise solutions that would help everyone, including the community of regular people and business owners who would most be affected by having a major league ball park in their front yards. Could there be mass-transit solutions connecting East Village with Power & Light? Of course. Could a lively street-level connection be developed to enhance the pedestrian experience from one location to the other? Surely.

For that matter, I still wonder whether it would make even more sense to build a new baseball stadium farther east in the Crossroads. This would create a logical synergy, efficiently connecting the Crossroads with the 18th and Vine District, perhaps even spurring a new east-west streetcar line. The Royals already have planted the Urban Youth Baseball Academy to the north of 18th and Vine. And the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is on the verge of raising money to build a new, expanded facility in the district. Hello, does opportunity knock? Some sentimentalists might also recall when the old Municipal Stadium at 21st and Brooklyn, just a few blocks east of 18th and Vine, operated under clouds of Arthur Bryant’s barbecue smoke.

If the April 2 tax proposal goes up in smoke, as it were, here is what I’m hoping: The Royals (not so much the football team) will get the message that they have to do better (not just as a baseball team). Team officials did a lousy job, or no job at all, connecting with potential neighbors and stakeholders south of Truman Road. They did a lousy job of understanding the history and potential future of the Crossroads. They tossed a horrendously wild pitch.

The Royals’ principal owner, John Sherman, is a decent fellow with a proven record as a supporter of the Kansas City community. I know it’s fashionable to denounce him as a billionaire, but so effin’ what if his heart is in the right place. I’m hoping he hears through the noise of hyperbole and, if the no-vote prevails, comes to a better solution.

If the tax passes on Tuesday, I hope Sherman will do a better job of listening. And I also hope there will be time and inclination to mitigate the impact a stadium construction project would have on the Crossroads. I had a waking dream one recent night that stadium architects could somehow peel back the northeast corner of the bowl in order to preserve, protect, and even enhance the occupants of the east side of Oak Street, from Green Dirt at 16th to the Chartreuse Saloon at 17th. (Ha, more wishful thinking.) We’ll just have to see what if any effect would come, presuming this goes forward, under the late-announced plan to keep Oak Street open.

I’m pretty much in the camp that neither the Royals nor their Truman Sports Complex neighbors will be going anywhere else anytime soon. Will the Kansas side try to lure them? Will more lies be told to keep taxpayers in line? Sure and sure.

Let’s just hope that good sense wins out, and, after the teams and Jackson County lick their wounds, they’ll come up with a more palatable Plan B. That’s B, for baseball.

From the Archives: Remembering Laura DeAngelis

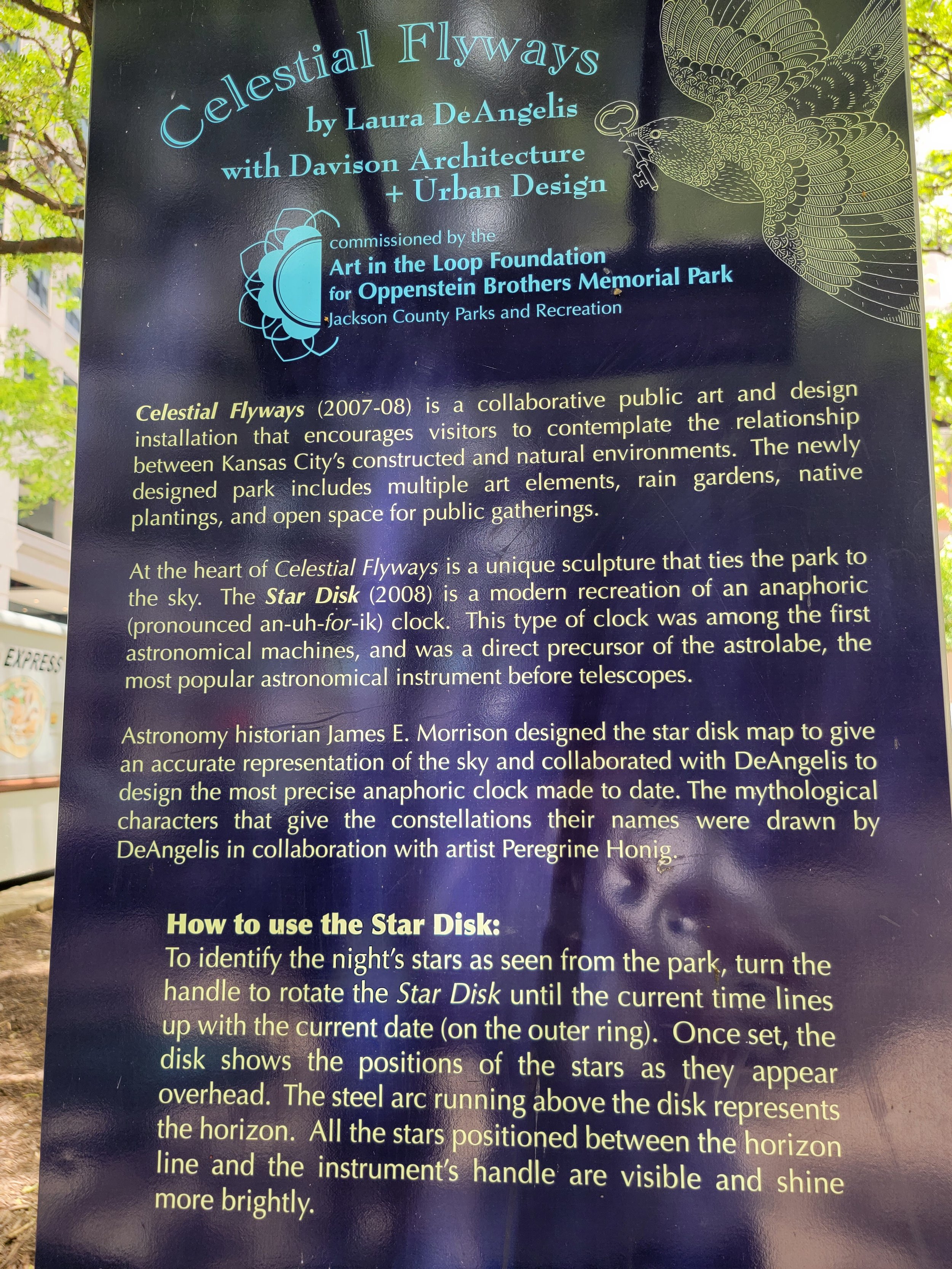

More than 14 years ago I spent a bit of reporting time following around the artist Laura DeAngelis, who was in the midst of creating a large public-art project in the heart of downtown Kansas City. She was a ceramicist, a visionary, a birder, and a gentle soul, who, if I recall correctly, also was an accomplished barista at Broadway Coffee in Westport. Well, those who knew Laura were saddened and shaken to learn this spring that she had died. Apparently, amid a mental-health crisis, she’d taken her own life. Laura had left Kansas City many years ago, and I’d had no contact with her, pretty much since I wrote this long magazine piece for The Kansas City Star Magazine. It appeared Jan. 20, 2008 under the headline “An Idea Takes Flight.” One corrective: When I dug out the story, I was horrified to learn that I’d committed a little crime against journalism: For some reason I can’t recall, Laura’s name appeared with a space in it (De Angelis) throughout the story. Mea culpa and apologies to Laura’s legacy and her family and friends. I’ve fixed that here. And another note: Not mentioned in the story, because Laura asked me to keep it out, was the presence in her apartment, in addition to her canary named Victor, of a crow she had rescued. She feared the wildlife authorities would not approve. I recently stopped by Oppenstein Park to gauge the current state of the installation, 14 years after its dedication. The park—property, I think, of Jackson County rather than the city—seems a little forlorn. And it’s hard to imagine that the mechanical star map still works (please correct me if you know otherwise). But it is nice to see that signage about Laura’s project as well as her metal bird medallions and lovely ceramic tiles remain in place.

By STEVE PAUL

Laura DeAngelis is bundled up against a wind whipped morning chill. She wears a brown quilted jacket and tan denim pants. A work crew is laying a bed of concrete in a vest-pocket park downtown, and DeAngelis, an artist, is about to make a gesture that’s the biggest of her short career.

She kneels down on pads atop the quickly firming concrete. She bends over and places a steel emblem of a bird—a finely detailed kingfisher with a berry in its beak onto the pavement-to-be.

Soon one of the workers, Mike Ward, takes over, further pressing the bird into the stiffening gray goo. He starts to clean the edges. It’s a fine bit of troweling and trimming that he keeps up for the next 30 minutes.

Fourteen more of the artist’s birds eventually will end up in the concrete. A wren, a green heron, a yellow-billed cuckoo. And that’s only the beginning of the transformation of Oppenstein Brothers Memorial Park.

The centerpiece of the redesigned park will be a 10-foot wide interactive map of the stars set on a base tiled in intricately carved ceramics, also from De Angelis’ hands.

At 12th and Walnut streets, the 7,000 square-foot- patch of urban calm has long been a symbol of civic renaissance—and failure.

Once described in this newspaper as a place where even the pigeons wouldn’t stick around, Oppenstein is on the verge of becoming the little park that could.

DeAngelis, along with a t3m of designers, planners, builders, bureaucrats and boosters, has been working for more than a year to make that happen.

The story of DeAngelis’ public art project, called “Celestial Flyways,” illustrates the complications that accompany the transformation of public space. But it also shows how a single artist can expand her creative vision, help forge a piece of civic identity and, despite the bureaucratic wringer that defines so much of the process, maintain her passion.

“I don’t think I had any idea how many aspects you had to deal with to make a public art project in comparison to being a studio artist,” DeAngelis says. “It makes you practice some good time-management skills. It makes you think that things should happen so much easier than they do.”

As a new graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute in 1995, Laura DeAngelis did her part to blaze the urban frontier. She spent four years transforming a third-floor industrial space on the northeast edge of downtown into a light-filled, high-ceilinged home and studio.

“I didn’t make a single piece of art,” DeAngelis, now 34, says of that renovation period.

Small teapots now line the top of a door frame. Ceramic tiles she designed cover the bathroom floor and walls. Her canary, Victor, chirps loudly in the sunny living room.

As an artist, DeAngelis frequently turns to the past for inspiration. The large ceramic, figural sculptures she has shown in recent years with great success, appear as if they stepped out of Renaissance canvases.

A few years ago, as she thought aobut applying for a public art project, she began wondering about the astrolabe. That ancient instrument helped astronomers reconcile time with the positions of the sun and stars in the sky. The astrolabe was a computer of its day—or, more properly, a slide rule, given its manual operation.

DeAngelis had encountered astrolables as a child at the Adler Planetarium in her native Chicago, which has one of the world’s largest collections.

“I’ve always loved old instruments,” she says. “They looked mysterious.”

While researching her project she found James E. Morrison, a retired computer engineer in Delaware, who had created a Web site devoted to the astrolable.

Seeing the chance to bring the wonders of the old tool to a wide audience, Morrison offered to collaborate with DeAngelis on her project. They soon decided it would be more practical to create a simpler device called an anaphoric clock.

A precursor to the astrolabe, dating back some 2,000 years, the anaphoric clock polots the sky and the passage of time but with fewer moving parts. That would make it more practice for a public, interactive installation, which here will mean a hand-cranked mechanism to align the date and time with the stars above the park.

“This will be by far the biggest anaphoric clock that’s ever been made,” Morrison says.

Morrison and DeAngelis e-mailed ideas and images back and forth. Morrison was impressed by his new astronomy student.

“She’s learned very quickly,” he says.

DeAngelis first proposed a public art project, including an anaphoric clock, at another down site, but it didn’t fly. When the Art in the Loop program sought proposals to re-energize Oppenstein Park, she was encouraged to try again.

As she studied the park, DeAngelis knew she wanted to connect people to the stars andto inject a sense of nature into the city.

“I’m in this very urban place, but I really love the country. I was thinking about all the things I love about the country and how I could bring it into the city.”

She was fond of running her dog along the riverfront, where, as a bird watcher, she took note of all the avian visitors who pass through mostly unnoticed. Scissor-tailed flycatchers, hooded mergansers—these are impressive travelers. “If you’re not looking for them, you don’t see them.”

DeAngelis also knew that to make a real impact on Oppenstein Park, she needed to come up with something more than a piece of so-called plop art.

“I started thinking not just about an art piece, but engaging people and getting them to stay in the park.

“Putting a sculpture in the park was not going to be enough.”

Encouraged by Art in the Loop to create a team of designers and engineers, DeAngelis selected Dominique Davison. Davison had recently established an architecture and urban planning firm in Kansas City with her husband, Robert Riccardi, after working for top architect Cesar Pelli out of New Haven, Conn.

Their plan evolved into a makeover of the park.

Davison proposed new landscaping, concrete planters and benches, and she worked with DeAngelis on aspects of the bird pieces and the placement and design of the star disc. The metal disc with include 496 holes, pugged with acrylic lenses, lighted from below. Visitors will set the current time and date, and the disc will replicate the stars above that very spot.

The disc will also have 50 constellation drawings by DeAngelis and Peregrine Honig etched into the surface.

In addition to the large tiles cladding the star disc wall, DeAngelis also designed a suite of smaller ceramics that will line the risers of three wide stairs. Those pieces will join the birds already set in the paving along with arced grooves in the concrete representing their migratory patterns.

The project won the Art in the Loop competition in October 2006 but, as these things go, rather than hunker down in her studio to produce the drawings and tiles, DeAngelis found herself sucked into the sort of process that rarely looks like art. Meetings and more meetings. For months.

A year ago, she and Davison and two dozen other people sat in a workshop downtown for parts of two days exploring the issues of public space. Consultants from the Project for Public Spaces in New York guided the locals through exercises on designing effective parts and plazas.

Among the participants was Bill Dietrich, executive director of the Downtown Council. When he arrived a few years ago to kick-start the council’s Community Improvement District, one of the top items on his to-do list was cleaning up Oppenstein Park.

Sprint Center was rising around the corner, H&R Block was moving into its new building a block away and the Power & Light District was coming out of the ground. With every sign of surrounding progress the park had become more central and more attractive as an urban experiment.

Dietrich, along with Art in the Loop’s Kate Hackman, gathered people who saw the need to improve the park not just for aesthetic reasons but also for a shared vision of community. County parks people and neighboring property owners found common ground.

“That’s new concept downtown: ‘Investing in public space enhances the value of my property,’ “ Dietrich said at the time.

After the workshops came months of working out details and solving technical problems of producing the metal birds and the star disc from DeAngelis’ detail drawings. The total budget—including the art works, site demolition and deconstruction, surveys, permits, contractor fees, signage, insurance—eventually was set at $475,000.

Meanwhile, DeAngelis tested ceramic ingredients and glazes. And she calculated every-shifting dimensions for the tiles she planned to carve, a mathematical process made more complicated by the curvature of the star disc base and the 13 percent shrinkage her pieces would undergo in the kiln.

Over the summer DeAngelis got a chance to extend her bird emblems beyond the park. The early arrival, a bird with a key in its mouth, got pressed into a new sidewalk across the street, on the southeast corner of 12th and Walnut.

One day she and her fiancé, Louis Rose, went to see it.

“it was covered in dust,” she remembers. “Louis spit on it to clean it up, and a security guard comes over and asks, ‘Why are hyou messing with the pigeon?’ “

“So we can see it better,” Rose replied.

DeAngelis was happy that the guard was protective of her artwork, but what she really wanted to say was, “It’s not a pigeon, it’s a rose-breasted grosbeak.

A few weeks ago DeAngelis stayed up all night to finish building a full-scale, quarter-section mockup of the star disc installation.

All of her birds had been pressed into the park’s new paving. A new planter wall and concrete benches were in place. Many of the tiles she had labored over with carving tools and a gentle touch had been fired and were awaiting placement on the site.

Installation of the star disc, which is being fabricated A. Zahner and Co., and most plantings will wait till late winter and a planned March reopening of the park.

For now, the mockup wedge sat in her living room as Art in the Loop board members, county parks peoples and other visitors got to see up close what the finished centerpiece would look like.

DeAngelis had even covered the low curved wall with plaster modls of the large tiles in progress, which include her stylized Missouri water lilies and curling, watery waves.

“This is going to be a lot more dramatic than I realized,” says David Miles, president of the H&R Block Foundation and board member of Art in the Loop.

Jonathan Kemper, of Commerce Bank, peppered DeAngelis with questions about the mechanics and materials of the star disc, the interior lighting and other aspects of the plan.

“This is cool,” Kemper says. “The color is fantastic.”

DeAngelis explains to Porter Arneill, director of the Municipal Art Commission, how she has put in hundreds of hours carving just the two largest tile, which she molded and repeated to make a total of 36.

Arneill notes how the public rarely understands how much work goes into these kinds of projects.

“We know more about how people make barbecue,” he says, “than we do about how all these artists make art.”

Victor, the canary, sings in the background.

Portrait in Love and Acid: On the Burns-Novick 'Hemingway'

My old newspaper, the Kansas City Star, which was Hemingway’s old newspaper, asked me to weigh in on the PBS biography, “Hemingway.” Why not? I spent a dozen hours watching the six-hour series twice and I caught eight of the nine pre-show panel discussions, which amounted to one of the most extraordinary promotional campaigns I’ve ever witnessed. I can’t say I’m one of Ken Burns’s biggest fans, but it’s hard not to be impressed by the sheer procession of material he and his colleagues manage to corral and by the compelling testimony they extract from their lineup of experts, several of whom I know. The documentary’s story line comes down to “he was complicated, more complicated than you ever thought.” Well, yes, but….Here’s a link to my essay-review:

https://www.kansascity.com/entertainment/tv/article250128694.html

Image above: Sketch by Luis Quintanilla.

From the Archives: Jay McShann and the Kansas City Sound

Lockdown has meant a lot of paper-shuffling, organizing, and weeding out. Every now and then something pops out of a folder that makes me smile. I feel so lucky at times to have had a chance to meet and write about so many gifted writers, artists, and musicians in my newspaper years. There was a stretch in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, after my stint as a jazz DJ, when I wrote quite a bit about jazz. As I noted elsewhere recently, at the time I wrote under the influence of Whitney Balliett, the great jazz commentator for The New Yorker. Close readers might catch a whiff of that influence in this review of a club date by the Jay McShann Quintet in October 1984. This was first published in The Kansas City Star, Oct. 14, 1984, under the headline “McShann provides showcase for KC jazz.” Along with McShann’s voice and piano, the band, playing at the Signboard Bar at the Westin Crown Center, included Budd Johnson, tenor sax; Carmell Jones, who’d long lived as an ex-pat in Germany, on trumpet; Noble Samuels, bass; and drummer Paul Gunther. I regret some of the cringeworthy prose, but I stand by what I hope represents a sense of some vital musical history.

By Steve Paul

Jay McShann, a national jazz treasure who calls Kansas City home, is in the middle of a monthlong stint, his fist extended appearance here in a couple of decades.

The homecoming in such a comfortable setting was long overdue and it should not be missed by anyone who professes an affinity to the pleasures of jazz.

A couple of sets Friday at the Signboard were notnecessarily a breahtaking evening of electrifying performances.

Rather, Mr. McShann—he’s been saying for a while that he’s 68, other sources say 75—and his colleagues delivered a populist sermon on the hybrid, swinging music that began emerging from Kansas City and the region a half century ago.

The program, familiar to much of the adience, included compositions by Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Mr. McShann and others. The presentation was mostly predictable: Mr. McShann out front for a couple of choruses, then solos by Mr. Jones, Mr. Johnson and, frequently, Mr. Samuels, before returning to an ensemble chorus to close.

But the allure of this living and breathing Kansas City jazz is not in the fundamentals of form. That simplicity is merely the springboard for the bounce of the blues-based sound.

Mr. McShann’s keyboard echoes with diverse influences: the austere economy of Mr. Basie, the frolicking barrelhouse of Pete Johnson and others, and often the more sophisticated textures of Art Tatum. His round face tightens up around the mouth as he concentrates on a two-handed boogie-woogie and then rolls and beams with pleasure as he manufactures a particularly offbeat phrase.

And then he sings. Tehre is something about that cidery voice: Its natural element is the blues.

Budd Johnson of New HYork, another septuagenarian, has been in and out of Kandsas City jazz circles over the years. His career includes stopovers with Earl Hines (early on and again in the 1960s), Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine and Count Basie. he blows a sweet, sometimes delicate sax. On Friday, the intensity of his delivery expanded with each solo as he and his colleagues fed from the collective pool of energy and ideas that grew all night.

On a featured number such as “Body and Soul,” Mr. Johnson showcased a versatile range and a style so easily presented that it must be, after all these years, indelibly etched in that abstract interior where music lives.

On Things Ain’t What They Used to Be,: Mr. Johnson, like his colleagues, didn’t stray too far from familiar ground, but he showed he can surprise a listener with a towering yelp or a beefy incantation.

Kansas Citian Carmell Jones has an aggressive but lyrical style. His phrasing was understated and controlled. Some solos were simply gorgeous.

At one moment early in the second set Mr. Jones seemed almost in awe of his surroundings. Mr. Johnson had just finished a chorus of “Confessin’ the Blues.” Mr. Jones began his turn with a simple four-bar entrance. Then he paused and said to the saxophonist, “That was beautiful. I don’t know what I’ll do to follow you.” Of course, he re-entered without missing a beat and then reeled off an exquisite, driven blues. That was it. No problem.

Mr. McShann is a true ambassador of the Kansas City style. He and his cohorts, finely dressed in black suits and formal shirts, are appearing at the Signboard (in the Westin Crown Center hotel) Tuesdays through Saturdays through Oct. 27. All shows begin at 9 p.m.

From the archives: Let's toast Roger Angell

Some FB chatter erupted today about the great Roger Angell, now 99, inspired by Joe Bonomo’s recent book about him (right) and a new Q&A posted this week at the New Yorker. All that sent me in search of a baseball column I wrote a few years ago as the Kansas City Royals were heading for the post-season (and ultimate victory in the World Series). I’d name-checked Angell, and I’m pretty sure I sent a copy to him, with thanks for a truly inspiring career, though I never got a response. In searching for the piece, I discovered that the NewsBank archive, accessed via the Mid-Continent Public Library, has an odd flaw—an apparent adversity to anything with embedded hyperlinks or fancy text coding. I think I’ve filled the resulting gaps accurately. In addition, I tripped over an earlier blog piece I wrote about Angell for The KC Star website, including a list of three of my favorite Angell pieces, and I’ve tacked on a copy of that at the end of this post. This first piece—yes, I can feel an Angellic tilt to some of the writing—appeared in print in the Kansas City Star on Sept. 27, 2015. If anyone finds it online, you’re a better sleuth than I am. The Star’s website often sucked.

A Fan’s Notes Emerge as the Anxious Season Peaks

By Steve Paul

I'll admit it: I left Wednesday night's Royals game at Kauffman Stadium before it was over.

It was the ninth inning. Relief pitcher Luke Hochevar had gone to a full count with three straight batters and let the third get on base. I had another one of those feelings that we've had so often in this crazy baseball September. Not tonight. It was already a given that the Royals wouldn't have clinched the division title that night, but still there was faint hope though not much optimism that the team would catch enough spark to get the job done.

On the way out of the stadium, I caught Hochevar on a monitor, luckily, closing out the top of the ninth with no further damage. On the drive home, we heard the Royals tie the game. Nevertheless the frustrating inability to get runners home — 14 batters stranded through nine innings — bode ill for this game. The agony lasted into the 10th.

It's hard to criticize the wussy people who had left the stadium even before my partner and I did. We'd sat in those hard plastic seats for four hours already. We're just real people with day jobs, and perhaps everyone else had an early appointment the next day, too.

Don't get me wrong. There were bits of exciting, scratch-it-out baseball; Yordano Ventura, the fiery and floppy hurler, looked fairly effective; and a big beer and a footlong brat helped fill the time and distract us from the goofy goings-on between innings on the giant scoreboard.

Even the newly minted fan in my house — to some faithful readers, that's the former She Who Is Not Easily Pleased — noticed the subtly intriguing dynamics of the game. "There was one moment when fans rattled Seattle," she texted to a friend. "Lots of drama. Guys talking behind gloves."

We got home just in time to turn on the radio broadcast and hear new closer Wade Davis shut down the Mariners in the top of the 10th and — at long last — the return of Royals ecstasy, when Lorenzo Cain drove home the long-legged Brazilian, Paulo Orlando, for the game-winning run.

In case you're wondering, I am not trying out for a spot on the sports page. But I am trying to get in touch with that thing about baseball that stirs in many of us even if our team weren't heading for another string of post-season battles.

I was glad that Wednesday night's game began with a moment of silence for Yogi Berra, whose death at 90 was reported that day. Sure he was one of those hated Yankees, but he was one of the very few who transcended that ancient rivalry to enjoy a kind of historic, heroic esteem. "That he triumphed on the diamond again and again in spite of his perceived shortcomings was certainly a source of his popularity," Bruce Weber wrote in The New York Times' lengthy obit.

My personal history with Yogi goes back to my ancient and brief days as a Little League catcher, like him, when all those Yankees were my heroes. This vivid passage last week from another hero, Roger Angell, The New Yorker's 95-year-old deep observer of baseball, stopped me in place: "I think of him behind the plate as well: a thinking bookend, a stump in charge."

Yogi's St. Louis heritage and school-dropout past meant nothing to me then or now, but I can't quite get over a sense memory that his visage always reminds me a bit of my grandfather, who hasn't been with us for 50 years now. He was something like a thinking bookend, too. Or at least that's how I remember him.

One thing we learned during the Royals' magical season last year was how intensely the game binds the generations. Will Salvador Perez endure behind the plate like a Yogi Berra for tomorrow?

I have watched or listened to almost every game this season, including the division clincher on Thursday. I'm ready to plan for October success. And to celebrate more baseball, which can make us anxious, break our hearts and, ultimately, lift our spirits.

There is that other thing about Yogi. I should've thought about it Wednesday night as we debated whether to stay or go. "It ain't over till it's over." One of the most classic Yogi-isms. And one of those Royals things we've been holding onto all season long.

—-

The following appeared online on Dec. 12, 2013, on the occasion of Angell’s receipt of a lifetime award from the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Roger Angell in the Hall: A real home run

BY STEVE PAUL

With drug scandals, end-of-season disappointments, and winter-meeting, team-building hiccups, the sport of baseball could seem like it’s in the doldrums.

But now comes news of a real grand slam: The Baseball Hall of Fame will honor Roger Angell with its J.G. Taylor Spink Award, which goes to those who chronicle the game in words.

Angell, who has long served as the fiction editor of The New Yorker, has also written classy, intelligent and deeply felt long-form pieces for the magazine over the last 50 years. Many of his pieces have been anthologized (see, for example, “Once More Around the Park.”)As his editor, David Remnick, opined the other day, “Roger Angell is the greatest of all baseball writers.”

Period. Underlined. No question about it.

Angell embodies two important passions in my life — baseball and writing — though I’m a relative newcomer to his work, given that I’ve only been reading him for three decades or so.

What makes Angell special is how he tells stories and how he always manages to find heart and humanity in the game.

For evidence, I’d offer up a triple-play of Angell’s classic pieces (and The New Yorker has helpfully posted one of them):

• “Down the Drain,” the aching tale, from 1975, of Steve Blass, a pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates who inexplicably went from top-of-the-game, World Series success to inexplicable oblivion (read it here).

• “Before the Fall,” another career-end story of a pitcher, the Kansas City phenom David Cone, then pitching for the Yankees (2001). “I was writing a book about Cone,” Angell writes, “but almost from the beginning he was aware that it wasn’t going to turn out the way we’d hoped.”

• “In the Country,” probably my all-time favorite Angell piece (I’ve used it in non-fiction writing classes). This one comes from 1981, and it starts with letters Angell receives from the girlfriend of a semi-pro pitcher named Ron Goble. Before you know it, you are witness to the pain and joy of these people, as baseball, cancer and sheer determination course through the lower levels, but entirely human stations of the game.

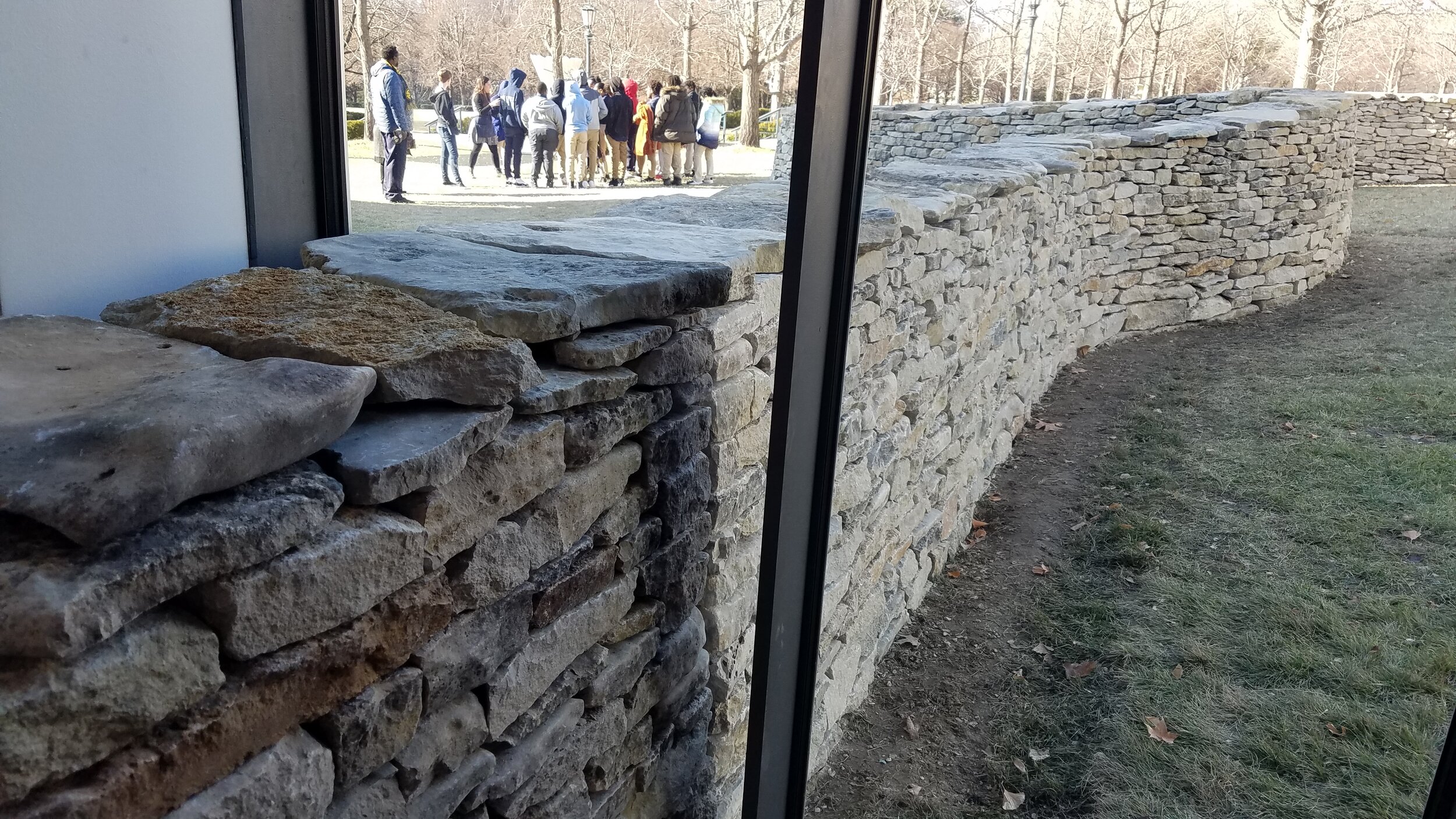

Goldsworthy's wall project rocks the Kansas City art scene

As Andy Goldsworthy launched his nine-month project to build a now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t “Walking Wall:” at the Nelson-Atkins Museum, I began to drop by from time to time to watch its progress. The grounds of the Nelson’s sculpture park, now including a green space to the east, across Rockhill Road, became a laboratory for Goldsworthy’s hand-made experiments in landscape, natural phenomena, and conceptual art. I wrote about the project early on for KC Studio magazine (find that one here). After the wall’s completion, I wrote another piece for the Art Newspaper, the global journal. The gallery above includes some of my favorite photos from the site visits.

Landmark KC Sculpture by Kenneth Snelson is Scheduled for Repairs.

“Triple Crown” at rest, lowered to the grown this summer and awaiting repairs to connection joints. Photo by Steve Paul.

Here’s another recent piece for KC Studio magazine. We posted it online in early September because it seemed to have some newsworthiness. The article will also appear in the November-December issue in print. I’ve long been entertained by this landmark sculpture. Of course, I just noticed that the trolls came out in force when a lousy local web site ridiculed it when linking to the piece:

http://kcstudio.org/after-nearly-30-years-kcs-floating-sculpture-needs-a-fix-kenneth-snelson/

Kansas City: The Dreamlike Life and Times

Google’s Arts & Culture operation recently launched a site devoted to Kansas City. It’s filled with praiseworthy stories and photos focusing on the city’s many cultural resources. I was asked to contribute a relatively brief history of the place, which turned out to be a fun exercise in research and compression. Find my piece here:

Kansas City Will Long Remember the Enduring Spirit of Henry Bloch

Although I’m out of the daily newspaper business, I hear from editors from time to time. So I turned out this tribute to a man who left a mark on the world.

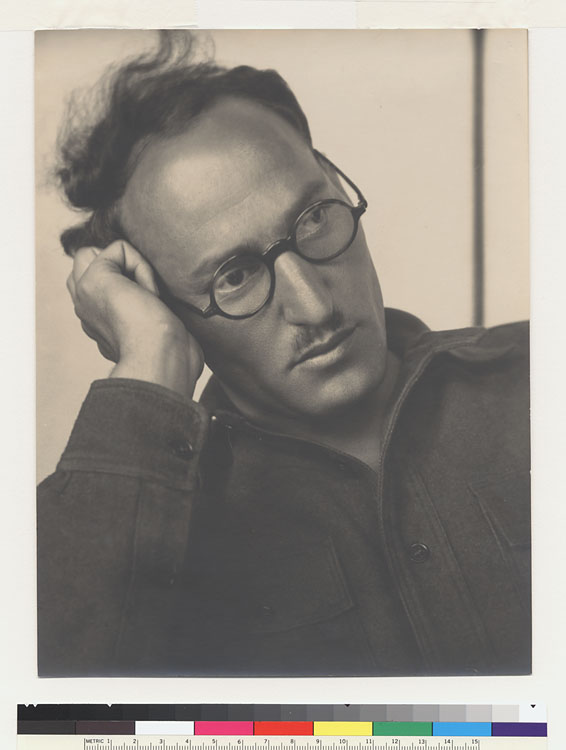

To Edward Dahlberg, 'Kansas City is a smutty and religious town'

A couple of years ago I gave a slide talk related to the Eighth Street Tunnel, a public works project that connected the heart of Kansas City with the West Bottoms by way of a trolley, or cable car, that rumbled through the high bluffs on the edge of downtown toward the stockyards and the original Union Station below. The tunnel has long been sealed, though it remains a curiosity for those who have a penchant for tucked-away pockets of local history.

My talk focused not on the tunnel per se but on the Eighth Street experience of a writer who grew up there but is not much remembered today. It occurred to me that the story of Edward Dahlberg’s boyhood remains a valuable and vivid Kansas City tale worth sharing.

Edward Dahlberg (1900-1977) was one of the 20th century’s most erudite and irritating writers. Born in Boston to an unmarried and itinerant mother, Lizzie, he and she landed in Kansas City when he was in short pants, about 1906.

Edward grew up on and around Eighth Street, where his mother practiced her profession as a lady barber. They lived in a flat in a stone house on “dilapidated” McGee Street, just off Admiral Boulevard, according to one of Dahlberg’s accounts, though a city directory also puts his mother at 710 E. Eighth St, which would have been a few blocks east of McGee.

Late in life, Dahlberg wrote this about his home town:

“I have never forgotten how I imagined an Eighth Street Kansas City brothel smelled. The prostitutes occupied rooms upstairs over Basket’s Chili Con Carne lunch counter, which was next to a saloon and the first lady barber shop in K.C., where part-time streetwalkers and fast chippies cut the hair of round-shouldered ranchers from Lincoln, Nebraska or Dallas, Texas.” There was indeed a restaurant operated by J.S. Baskett, two Ts, at 12 E. Eighth St.

Lizzie first worked for someone else, but eventually opened her own shop, the Star Lady Barbershop, at 16 E. Eighth St. She first appears at that address in the Polk’s city directory of 1911. The streets and the situation were not always kind to the introverted boy, and at one point, when his mother’s long hours of work and complicated relationships with men became too much for her, Lizzie sent Edward off to a Jewish orphanage in Cleveland. When he returned to Kansas City a few years later as a young adult, he worked in the stockyards of the West Bottoms and became increasingly embarrassed by his mother and her occupation. He left for Omaha and points west, then eventually New York, where he managed to obtain an education in the classics at Columbia University in the mid-1920s.

Dahlberg memorialized and rhapsodized over his mother in his autobiography, Because I Was Flesh, published in the mid-1960s. The book is poetically lush and feverishly frank about personal and sexual anxieties. It’s full of classical and biblical allusions, elevated language that could stop a casual reader in her tracks, and colorfully resonant descriptions of Kansas City in the early 20th century.

The town was not a senseless Babel: the wholesale distillers were on Wyandotte, the commission houses stood on lower Walnut, hustlers for a dollar an hour were on 12th and pimps loitered in the penny arcades between 8th and 5th on Main Street. If one had a sudden inclination for religion he could locate a preacher in a tented tabernacle of Shem beneath the 8th Street viaduct, and if he grew weary of the sermons, there was a man a few yards away who sold Arkansas diamonds, solid gold cuff links, dice, and did card tricks. Everybody said that vice was good for business, except the Christian Scientists and the dry Sunday phantoms who lived on the other side of the Kaw River in Kansas City, Kansas.

Dahlberg, like many writers, ended up in Europe in the 1920s. And there he produced his first novel, Bottom Dogs, which was published in 1930. D.H. Lawrence wrote an introduction. The critic Edmund Wilson said “Bottom Dogs is the back-streets of all our American cities and towns,” and some readers eventually identified the book in a line of “proletarian naturalism” linking him with the likes of James T. Farrell and even Jack Kerouac.

In Because I Was Flesh, Dahlberg revisits and essentially rewrites that first book, turning his fictional character and his mother Lizzie into the real characters of memoir.

In both books, Dahlberg writes about growing up in the shadow of the Eighth Street Viaduct, which spanned a few blocks beginning at Walnut and heading west toward the Eighth Street tunnel. Lizzie Dahlberg’s shop stood beneath the viaduct and next door to the Electric Fish and Oyster House. Wouldn’t you want to have the chance to dine again at the Electric Fish and Oyster House in downtown Kansas City?

Dahlberg must have read another book by a onetime Kansas Citian. Clyde Brion Davis, a newspaper man who once toiled at The Star, penned an autobiographical book called “The Great American Novel…” in the late 1930s.

Davis arrived in Kansas City around the same time as Dahlberg, 1907. From the Union Station in the West Bottoms he was directed to a wooden runway that led to the elevated station. “And presently I was rattling along in a trolley car over the roofs of factories and railroad tracks and thence through the Eighth Street tunnel and into the hilliest and most hectic city I have ever seen. No Kansas Citian walks along the streets. He travels at a half run. It is easier to skip down the hills than to hold back in a dignified walk. And the momentum helps climb the hill ahead.”

Davis also wrote about the street life underneath the Eighth Street Viaduct:

It “cuts a heavy black span across sun-drenched Main Street and Delaware and throws an equally black and cool shadow beneath. A few wagons and drays plod up the hill beside this shadow, but underneath the viaduct and around the pillars is a haven for the weary and heat-stricken. And here is the gathering place for that remarkable clan known as ‘street fakers.’ There is Peters who sells Magic Oil….There is Edwards with his straw hat and red, white and blue hatband and beery breath who is ‘advertising’ Arkansas diamonds. … There is the street faker with the patent potato peelers and the one with the revolutionary cleansing cream.”

Davis doesn’t mention the Star Lady Barbershop, but surely he encountered Lizzie in one shop or another under the viaduct and perhaps even sat in one of her chairs for a trim and a scrape as the city buzzed outside and the streetcar trundled overhead.

When Edward Dahlberg left Cleveland and returned to Kansas City he was 17 or 18. It’s tempting to consider that he might have been here around the same time as Ernest Hemingway, who was working as a reporter for The Kansas City Star (in 1917-18). They were about the same age. But there’s no existing correspondence between the two of them and no evidence that I’ve yet turned up that each was aware of the other’s life in Kansas City. I’d add however that in the ensuing years, Dahlberg developed a strong dislike of Hemingway and his work.

When he came back, though, Dahlberg found what he felt like was a changed place: “The city was now filled with Christian Scientists, spiritualists and impecunious bachelors who went to the tabernacles and religious gatherings to meet spinsters who thought maidenhead and godhead were indivisible. The city was no longer my parent. I could not saunter along Locust, McGee and Cherry Streets. Kansas City had become a great, soulless town, and the laughter had expired underneath the 8th Street viaduct.”

It’s possible, of course, that what had changed was Dahlberg’s sensibilities rather than the city. He was no longer seven years old. He was a young adult, on the verge of exploring his own future.

Lizzie Dahlberg owned her barber shop at least into 1925 or so. She wound up owning one or more houses in North Kansas City and Northmoor. I think I have copies of some letters that Dahlberg wrote to Sherwood Anderson from one of those houses, perhaps after Lizzie had died.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that Edward Dahlberg returned to Kansas City as recently as 1965 to be a writer in residence at UMKC. I once heard from an English teacher there that Dahlberg was very much the dirty old man that he sometimes revealed himself to be in his books. Not to excuse his behavior, but that was the world he had grown up around, in that “smutty and religious town,” in those turn-of-the-century years.

In the end, Dahlberg turned on the city of his eye-opening youth: “Homer detested Ithaca, and let me admit, I hate Kansas City, which is still a wild, rough outpost town of wheat, railroads, packing houses, and rugged West Bottoms factories.”

Echoing Thomas Wolfe and others, Dahlberg concluded, “Nobody ought to return to his native city; it’s a premature burial, and yields nothing but a terrible sickness of the mind.”

Sources

Because I Was Flesh, by Edward Dahlberg. (New Directions, 1967).

Bottom Dogs, by Edward Dahlberg (City Lights, 1961).

“The Great American Novel…,” by Clyde Brion Davis (Farrar & Rinehart, 1938)

The Leafless American & Other Writings, by Edward Dahlberg (McPherson & Co., 1986)

Flash Fiction: My First Noir

Fiction — writing fiction, that is — has never worked very well for me. This year I’ve been making another run at it. In the crevices around the larger project and a few smaller ones I’ve managed to turn out one story still in progress, one story that felt done enough to submit just recently, and a piece of flash fiction that editors at Akashic Books were kind enough to include the other day in their online series Mondays Are Murder. Akashic is the house that published Kansas City Noir, the fiction collection I edited featuring 14 writers, in 2012. My story here (follow the link) is in Akashic’s Noir anthology style, set in a specific place (Midtown Kansas City). Locals may well recognize the opening setting, daytime in Milton’s Tap Room. And squeamish readers might be aware there’s a NSFW moment near the, uh, climax.

http://www.akashicbooks.com/blue-is-the-color-of-night-by-steve-paul/

From the Archives: Checking Out of Reality TV and Into a Folk Alliance Weekend

The Folk Alliance International conference is coming up again in Kansas City. For four glorious days in February I plan to immerse myself in a mind-blowing kaleidoscope of musical experiences. This will be the fifth and last (for now) KC conference, and I can hardly wait. I was poking around in search for something this morning when I came across the following, a quasi-political column that I wrote on the verge of Folk Alliance in 2016 and as that horrendous presidential campaign year was unfolding. I don't think I knew at the time that I'd be retiring just a month or so later. This column first appeared at kansascity.com and The Kansas City Star on Feb. 19-20, 2016. Sorry if it takes you back to a scary place.

"Steve Paul: To quote a sage, this land is your land"

By the time you read this I expect to be in the midst of a lost weekend. Yes, I suffer from an uncontrollable addiction — to music — a condition that has been exacerbated by the annual influx of song slingers and guitar players who gather at the Crown Center hotels in Kansas City for the Folk Alliance International conference.

I’ll spare you some of the high points of lyrical heartbreak, dextrous finger-picking and free-form, nocturnal goings-on of the “folk tribe” to which I pay tribute.

But I will thank the organizers for providing a timely and immersive break from that other tribal ritual consuming so much air space these days. Most of the music-making has taken place out of range of any 24/7 news coverage of the presidential campaign, and I’m happy even to give up glancing at my Twitter feed for at least an hour or two at a time.

That’s not to say this presidential campaign has unfolded without a certain entertainment value. But, Donald Trump in a pissing match with the pope? Who could have seen that coming?

Speaking of torture, the results from two more contests will be flowing into our screens this weekend. It has been difficult to sense any shift from recent trends in momentum, which has the leading candidates of both parties locked in unexpectedly close and death-to-the-finish battles.

If we’re lucky, the Republicans could lose a candidate or two after this weekend’s results. (When exactly will Ben Carson get the message that, aside from not having a clue, he doesn’t have a chance?)

As the GOP field narrows, it won’t be quite so easy for Trump to dominate in the race for committed convention delegates. With fewer candidates in the mix, runners up will have a better chance to reach voting thresholds (often 15 or 20 percent) that will allow them to land apportioned delegates.

So the acid-drenched battle, primarily between Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, for second and even third place will mean more as the race churns through the Super Tuesday contests (March 1), Michigan (March 8) and a group of meaningful primaries in the middle of March.

Among the Democrats, it’s fair to ask the Hillary Clinton camp exactly when and where did they miss the signal that Bernie Sanders was riding forth on an express train.

Did anyone expect that Nevada, with its large Latino and union factions, would wind up neck and neck? It’s quite reasonable to suggest that Sanders’ message of income inequality resonates in a place that is so much defined by the haves and have nots and so largely populated by those who toil to serve the wealthy.

Clinton’s baggage remains heavy, though a majority of Democrats still view her as the party’s best chance to defeat whichever contorted Republican survives his party’s offensive demolition derby because, of course, no candidate is ever perfect and no politician is ever an angel.

Sanders’ appeal to the idealism and rebellion of youth (and many of their feel-the-Bern elders) will be a strong storyline when the history of this presidential campaign is written. So will the utterly surreal and weirdly American story of Trump, no matter what happens in the coming months.

I’m looking forward to dropping out for a couple of days. It might feel something like having a real life, not a constant loop of polling updates, attack ads, verbal inanities and solemn dissection of all of the above. I’ll miss the Sunday morning shows. I’ll take the news in small doses.

Maybe I will think a bit about Nevada this weekend, given that I’ll be holed up inside a hotel where time will stand still and machinations of the outside world will hardly penetrate. Just like Vegas, that is. But for this weekend at least I’m hanging my hat with the music makers. And if there’s any justice in this world, they are the ones who will inherit the earth.

This food thing: A sweet and melancholy affair

I have a large appetite. Food is not just nutrition but celebration. And life is too short to eat boring food, just as it’s too short to drink unremarkable wine. So I splurge sometimes. I cook with focus, adventure and a kind of subdued passion. I go for new tastes.

Yet, lately, I tend to eat less. Call it diabetes discipline. That’s optimistic. The numbers are good, though my liver would tend to disagree. Still, if tempted with a whole roasted fish or an oozing burrata with smoked trout roe, I’m all over it, at least for a few bites. Turns out that a heaping plate of crispy beef from a local, old-reliable Chinese restaurant can remain the centerpiece of four leftover lunches. I mean, why stuff yourself?

These thoughts began arising as I read a new collection of the late Jim Harrison’s food-and-life essays. The book’s title, A Really Big Lunch, refers to a spectacularly excessive, 37-course feast (or was it 42?) put on by a French chef and friend of Harrison’s. Even Harrison, whose appetites clearly were larger than mine, felt overwhelmed, almost defeated at one point. Harrison holds nothing back as a writer, and some readers might be turned off by his lecherous confessions and old-school impropriety (the essays reach as far back as the 1970s). But looking past all that, which, in the current sexual-harassment environment, becomes admittedly harder to do, he has wise and entertaining things to say about food and wine. I plan to cherry-pick some of Harrison’s wine writing for a paper I’m planning to give at a Hemingway conference, in Paris, in 2018. And imagine my surprise when I realized recently that in my modest collection of bottles I’ve got a Domaine Tempier Bandol from a few years back, which apparently was Harrison’s favorite wine in the world.

So, food, wine and cooking. From time to time I pay attention to the appetites.

On a fall Saturday, with nothing much else going on, I turned some of the last of our yard tomatoes into a marinara. They were not lovely orbs. They weren’t even deeply red, but they would do for a kitchen improvisation. It took a while in boiling water to loosen their skins, but when that was done I set them aside to cool. Chopped onions and garlic and the last of some baby carrots in the fridge. I was hoping to add tomato paste to the simmering stew, to add some color and heft, but alas I could find none on the shelf. Here’s a suitable substitute: a small jar of prepared tapenade; hmm, red peppers, some kind of cheese, why not? The tapenade turned the marinara a bit orange, but with salt, pepper and dried herbs, it all tasted pretty fine nearly two hours later when I turned off the burner. I put some of the marinara in a bag to freeze, and held out a good portion to eat the next day.

One Sunday, we found some frozen lamb chops in the freezer. I chopped onion and garlic. I opened a red wine (a mass market red Zinfandel) and a jar of vegetable stock I’d made around Thanksgiving. Ta da: braised lamb, with little potatoes and carrots. We ate lamb chops for days.

As a onetime restaurant critic, my radar remains fairly well tuned when we go out to eat. Yet, I failed myself on a recent trip to Toronto. Though I managed to sample a decent variety of tastes in a couple of days – pub food, tapas at a trendy Sherry bar -- I missed the hugely important world of alluring Asian cuisines that seem to define dining in that capital of cultural diversity. Next time, for sure. A recent trip to Atlanta gave us a sampling of that city’s burgeoning fine-dining scene, though we barely scratched the surface. In Boston this fall, at the Neptune Oyster Bar (pictured), I managed to consume some of the finest oysters on the half shell I’d ever met. In Kansas City, I’ve sampled a couple of promising new restaurants lately and always find pleasure and creativity when returning to old favorites (Novel, the Rieger, the Antler Room, to name just three). And I had one of the best meals of the year when birthday splurging in Corvino’s Tasting Room (details in a previous blog). But I always have to remind myself that some of the other best meals of the year occurred in domestic settings: A humbly generous and bustling family meal around an extended kitchen table at the Zia Pueblo in New Mexico; an intimate and poignant Thanksgiving tribute with family members of a close friend who had died just the week before.

With the holidays in full swing, I expect much feasting ahead, some of it happy, some, so it goes, melancholy. The warmth of the kitchen, the clink of glasses, all that love on our plates – sure, we can’t help but feel grateful for what we have.

De Gustibus: A 12-Dish Tour in Corvino's Tasting Room

During my kaleidoscopic career in the newspaper business I spent a few years as a restaurant critic. Once a month or every six weeks or so – along with whatever other writing or editing I was doing at the time - I analyzed meals and experiences at Kansas City restaurants. Every now and then I’d write about food experiences during travels elsewhere (Washington, D.C., Seattle, Paris, an American Royal barbecue immersion). I mostly enjoyed chowing down during a period, not so long ago, when Kansas City was increasingly being led forward by a new generation of creative chefs and food-and-beverage professionals. I can’t deny that restaurant writing and the most hedonistic and self-conscious aspects of the scene sometimes resemble a kind of food porn. So be it. Who doesn’t really like a sexy picture of an assemblage of desirable pleasure on a plate?

I suppose a similar thought occurred the other night more than once during a three-hour dinner in the Corvino Tasting Room. This is the fixed-price, multi-course menu that unfolds out of the view of the sometimes raucous main dining room, or Supper Club, at Corvino and within whisper distance of the kitchen. (Along with four generously sized four-top tables, two counter stools offer ringside views of cooking and chef-ing in action.)

My experience at Corvino had been limited to a dinner, some drinks and some late-night noshing off the attractive (and attractively priced) menu that kicks in at 10 p.m. Food was always good, or at least interesting. Service was sometimes surprisingly ragged. Some recent staff turnover seems to indicate the place is still finding its way. But with a foundation based on Michael Corvino’s exquisite and exciting approach to food, its future is highly promising.

I didn’t intend this post to be a review. But I will say that of the dozen dishes put before us, from the opening amuse bits to the closing sweets, not a single false note occurred. There were rich and tempting notes of chicken liver mousse and foie gras. Sweet and savory danced a pas de deux all night long. An oyster topped with a melon granita and chile, was an early, winning example of the dynamics of texture, color and palate-enlivening sensations that Corvino revels in. I would return to his kitchen if only to savor another bowl of the corn pudding, bedded down with chanterelle mushrooms, trout roe and a dusting of buckwheat. The “main” dishes included a succulent King salmon and a plate with two contrasting cuts of ribeye. After opening with a glass of Champagne (Jacquesson 740), I asked sommelier Ross Jackson to suggest a bottle to carry my table of four through the middles and mains. The Burgundy “Les Bons Batons” (2014), by the female winemaker Ghislaine Barthod, was light, slightly earthy and perfect.

The Tasting Room, to be sure, is not an everyday experience. It’s a special-occasion place, where you should expect to drop a couple of bills per person. Or more. Much more. (We skipped an optional caviar plate and a $50 upcharge for A5 wagyu – the highest rated and rarest version – on the beef plate, though I’m sure there are plenty of big spenders who’d spring for either experience.)

Kansas City’s dining scene continues to expand and excite. With its prominent place in a food-centric vortex of the Crossroads Arts District, Corvino clearly is a trend setter. Its lovely gray-hued main room – the space designed by a top-shelf architecture firm, Hufft Projects –includes a thoughtfully made stage for musicians, a rarity, but a welcome one, for restaurants. Here’s hoping my spheres of food and music friends will continue to happily collide there.

What's that wine in your glass?

Doug Frost is a bona fide treasure in the wine world. As a Master of Wine and a Master Sommelier -- that's an extremely rare combination of achievements -- he's got highly developed senses and a brilliant way of teaching the intricacies and boosting the pleasures of this life-affirming liquid. On Monday he joined the Gang of Pour group of Kansas City somms and restaurateurs (and somewhat educated observer-participants such as me) for a session on blind tasting. In blind tastings, of course, wine bottles remain in brown paper bags or otherwise hidden and tasters try to figure out what's in the glass. It ain't easy, but Doug has a way of making it logical and breaking it down to the elements that help you learn your way.

The Gang of Pour sessions now meet every two weeks at the lovely Ca Va bubbles spot in Westport and are open to KC bar professionals. This one was illuminating, exhilarating and rather difficult. Future sessions, led by a variety of wine pros, promise to be equally enjoyable.

Doug follows a consistent procedure, tied to the grid sheets used in sommelier certification exams. So we go through a fairly specific list of wine characteristics (color, hue, intensity, aromas, tastes, structural qualities) in order to get to a logical place in identifying each wine. Describe the floral and vegetal notes. Is this a warm climate wine or a cool climate wine? And why? How do you describe the levels of acid, tannin, and alcohol -- low, moderate, moderate-plus or high?

Doug spent a good part of the first hour of the session walking through each incremental step as it applied to a certain white wine. Then my classmates (about 20 of us) and I blasted through five more wines -- a second white and four reds -- having about four minutes each to make our IDs. For the record, I was mostly humbled, though I felt fairly good about some of my sensory responses, especially in analyzing structure. In the end, I did nail two of the six wines: an Australian Shiraz and a New World Pinot Noir (it was from New Zealand, but I couldn't get past New World, though probably would have landed on Oregon instead).

I've been learning from Doug for more than 20 years. He is not only incredibly on top of everything, he's got a great sense of humor, he's brutally frank, and he's totally committed to making wine drinking both fun and rewarding.