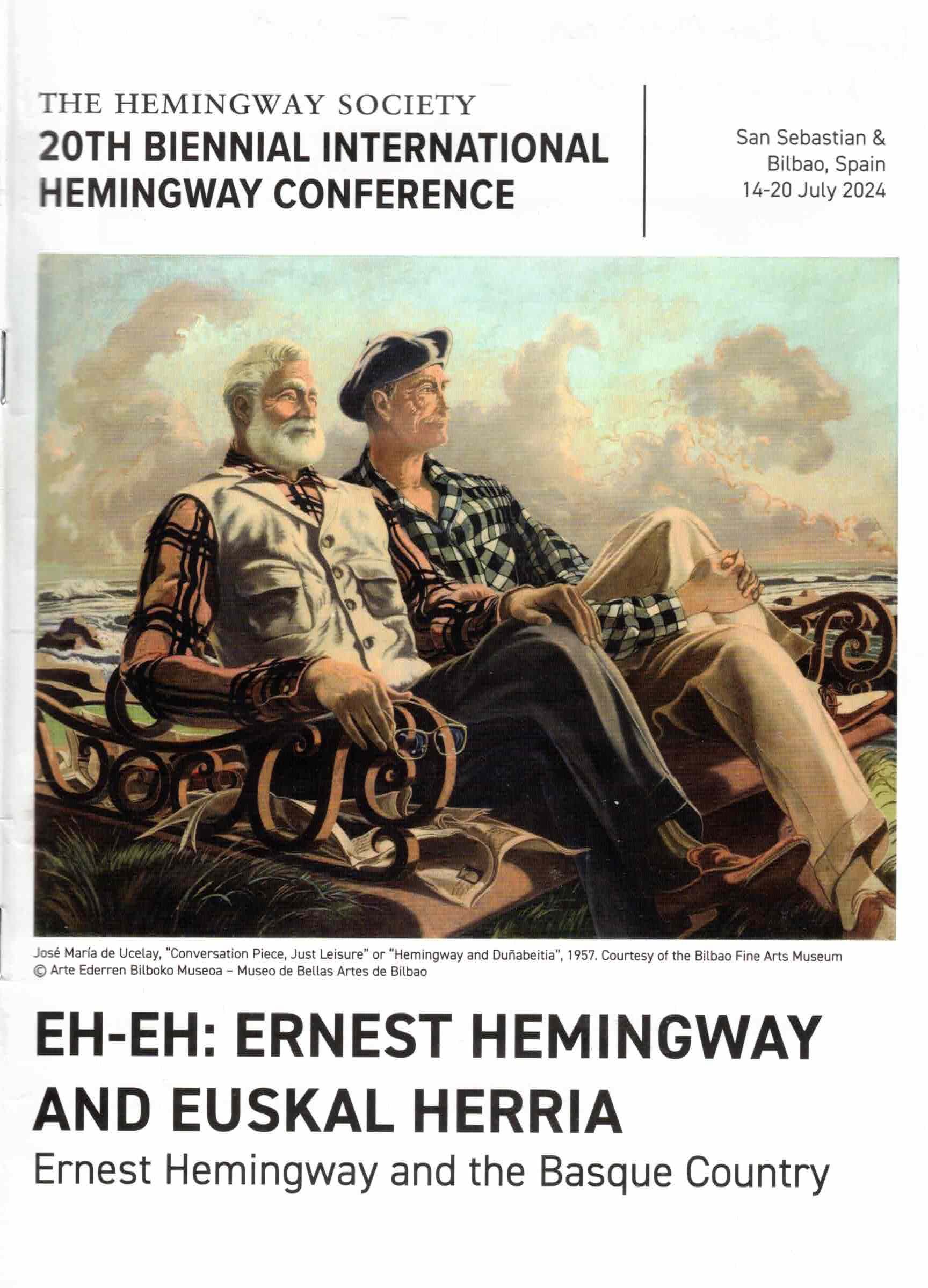

Gathering some of the notes and photos I posted on FB during our excursion. The main event was the 20th Biennial International Ernest Hemingway Society Conference in San Sebastián and Bilbao, Spain, or Basque Country, Euskal Herria as the locals would rather hear it. I’ll aim to expand and revise as I proceed, so this post may evolve over time, especially as I look deeper and more critically at photos.

Wednesday, July 10, Barcelona

Didn't take long to absorb a new appreciation for Joan Miró at his @fundaciomiro in Barcelona. What a gorgeous spread of the surreal spirit. First taste of Barcelona after a long travel day was a pretty fine Italian sandwich from a place near our hotel. Later, for early din, we had what might be the first of a long series of tapas on this journey, with a Vermut aperitif and a glass of Spanish red. First Gaudi sighting: the Guell Palace. No encounters with anti-tourist protestors, but the place and its narrow alleyways are certainly abuzz with people. You can hardly avoid La Rambla, the main pedestrian thoroughfare. Struck me something like Duval Street on steroids. IYKYK. Closed out the day in the hotel bar watching England shock the Dutch in the Euro.

Thursday, July 11, Barcelona

Gaudi: Casa Battló

It's rather impressive to see how much the experience of Barcelona involves the architecture of Antoni Gaudi. The city's ancient stone bones share the spotlight with Gaudi's pop-eyed, playful, curvy, and sensuous inventions. There's of course the Sagrada Familia, still under construction but nearing completion after all these years. We got immersed in Casa Battló, one of the most brilliant architectural redos you'll ever see. The tour experience (jammed with people) begins and ends with contemporary psychedelic dreamscapes. The latter is an AI creation by Refik Anadol, whose earlier deployment of collection data turned a huge wall at the Museum of Modern Art in NY into a plasmatic performance of bursting color.

Friday, July 12, Barcelona

Given we'll soon be immersed in Hemingway world, I was happy (not the right word) to trip upon an exhibit of art and the Spanish Civil War at the Museu Nacional D'Art de Catalunya in Barcelona (below)). Stunning and painful images of all kinds, including another Miró.

Sunday, July 14, San Sebastián

Before the opening of our Hemingway conference tonight in San Sebastian (Donostia, as Basque people call it), we went to a civic cultural center to see an exhibit of Hemingway's long experience with Basque culture, people and places. Saw some images and info I was unfamiliar with, so enlightenment happened.

Tuesday, July 16, San Sebastián

The 20th International Ernest Hemingway Society enters its third day later today in San Sebastián, Spain. On Monday I moderated one panel and gave a paper (on the short story "After the Storm"), so now my "work" is done. It's great to be among old and new friends, and to marvel at all the good research being done by scholars and writers in various fields (marine biology, geography, journalism, fiction, poetry, dance, art, food) and from all over: Spain, of course, U.K., Georgia (republic), Serbia, Japan, France, U.S. and Canada. And, in San Sebastian, a scenic, seemingly prosperous place, some of the world's best eating beckons day and night. Last night we elbowed our way into a pintxos bar that, on good authority, was a favorite of Anthony Bourdain's: a bacalao dish and lengua en salsa were delicioso. And the vermut (on the rocks, with an orange slice, which we've been sampling nightly since we started in Barcelona) had a distinctive essence of thyme in the nose. Will have to go back to view the bottle. More panels today and dinner honoring our young scholarship recipients at a cidery.

***

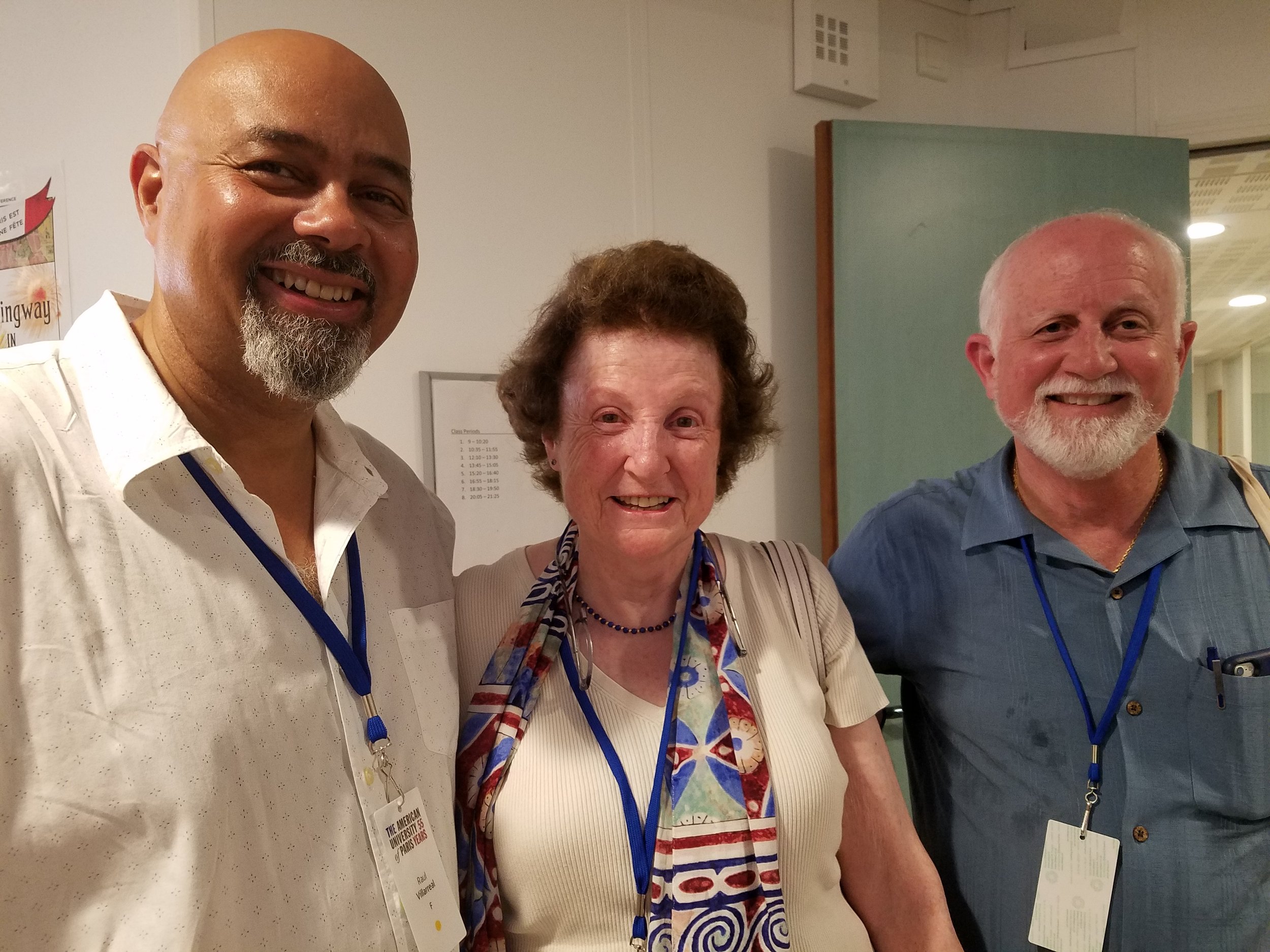

Elena Zolotariov (right) is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of London. We met in Wyoming a couple of years ago. She is the real deal and represents the future of Hemingway studies. She introduced me to two attendees from Georgia.

Wednesday, July 17

This morning we leave San Sebastián for Bilbao on a bus trip via a noted winery. Tuesday (I think it was) brought more deep dives at the Hemingway conference. We heard from the editorial team at the Hemingway Letters Project, which has just produced volume 6 of his collected letters, another big book covering less than two years, 1934-36. Other papers we heard examined aspects of dance, prompted largely by The Sun Also Rises (glad I reread it on the flight crossing the pond a week ago), Hemingway on film (especially as used by teachers), as well as the work of Martha Gellhorn, the writer and unhappy survivor of EH's marriage No. 3. In town we returned to the little Haizea Bar for breakfast and wound up the evening at a cidery for a dinner and drinkfest honoring the young recipients of Hemingway Society travel and research grants.

I was honored to be included on a panel with Japanese scholars Kaori Fairbanks and Hideo Yanagisawa, with whom I've been acquainted for many years.

***

Wine was the theme of our excursion toward Bilbao on Wednesday. A visit to the Marques de Riscal wine estate, where Frank Gehry built a hotel expansion in 2006 (inset; no time to look inside, so this was just a tease before our visit to the Guggenheim Bilbao on Friday.). A fabulous restaurant lunch, with generous pours of bianco (Verdejo from the Ribera de Rueda) and the Rioja region's predominant tinto (Tempranillo). A stroll through the walled village of Laguardia, including a guided tour of a wine producer's cave inside the town's medieval system of elaborate tunnels.

Thursday, July 18

A musical interlude for my friends in The Hemingway Society: Today at the proceedings of our international conference in Bilbao, Spain, one session served as a tribute to two recently deceased Hemingway scholars--Donald Junkins and H.R. "Stoney" Stoneback. Mike Roos sang his song "The Unfinished Church," which draws from scenes in The Sun Also Rises and was encouraged by Stoney. In addition, two former students of Stoney at New Paltz, Alex Pennisi and Joe Curra, played the late Jerry Jeff Walker's great early road song about our friend Stoney. I once interviewed Walker and got to discuss our mutual connection with Stoney. Always loved this tune, even before I knew Stoney. Both vids on my YT site.

https://youtu.be/CbqhADOOZ1M?si=MBc7SfzsiPC3715X

https://youtu.be/Gs-BXK7u6KE?si=fbw4UfW-w42c54zq

***

First glimpse last night of Gehry's Guggenheim in Bilbao. We'll spend time there later today. At Thursday's Hemingway conference sessions: Linda Patterson Miller (l), author of the landmark essay "Why I love Papa," talked about rattling the male scholars' cage back in the 1980s, helping to open Hemingway studies not only to female scholars but also to female and personal voices in writing (including Ann Putnam at right). This led to lively discussion of the longstanding tussle in academia over first-person prose and memoir. This is somewhat similar to what we talk about in my overlapping world of biography, the hybridizing of the craft with memoir. Big topic, long story for later. With the public domaining of The Sun Also Rises, we heard from four editors who have produced four(!) distinct new editions of EH's first novel, one for public consumption, three aimed at classroom use. The projected final volume of the Hemingway Letters, expected to be pubbed in the 1940s, is being worked on now because we still have Valerie Hemingway in our midst, and she was right there as EH's secretary, taking his dictation for most letters in 1959 till the end, in '61. Jerry Kennedy had a brilliant take on those last years, including the travails of The Dangerous Summer, and Michael von Cannon described the editing process and other discoveries for Vol. 17. Later: a pelota (jai alai) demonstration, pintxos and drinks with friends and nightcap with a good crowd at the hotel lounge, conveniently located down the hall from our room.

Friday, July 19

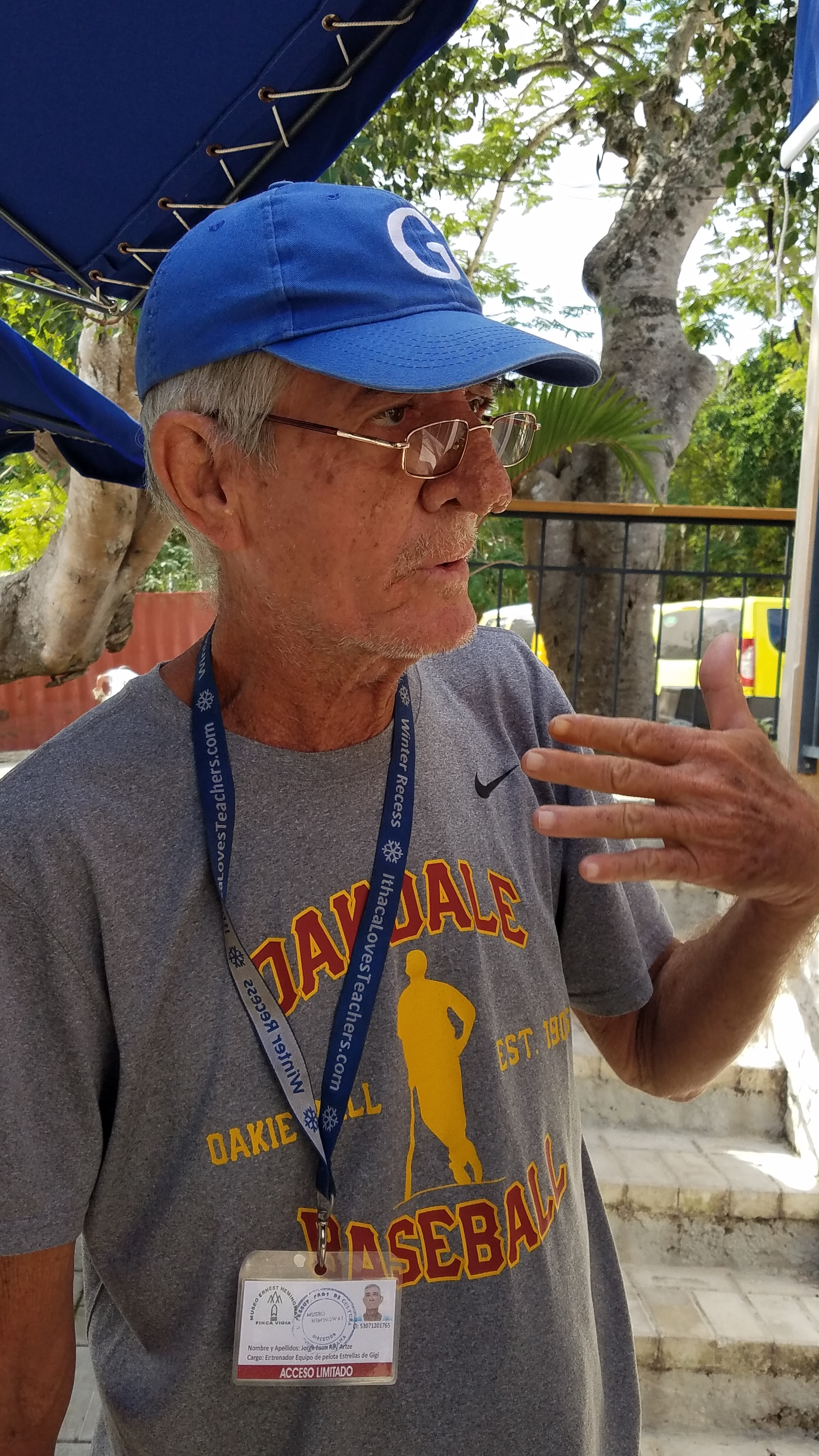

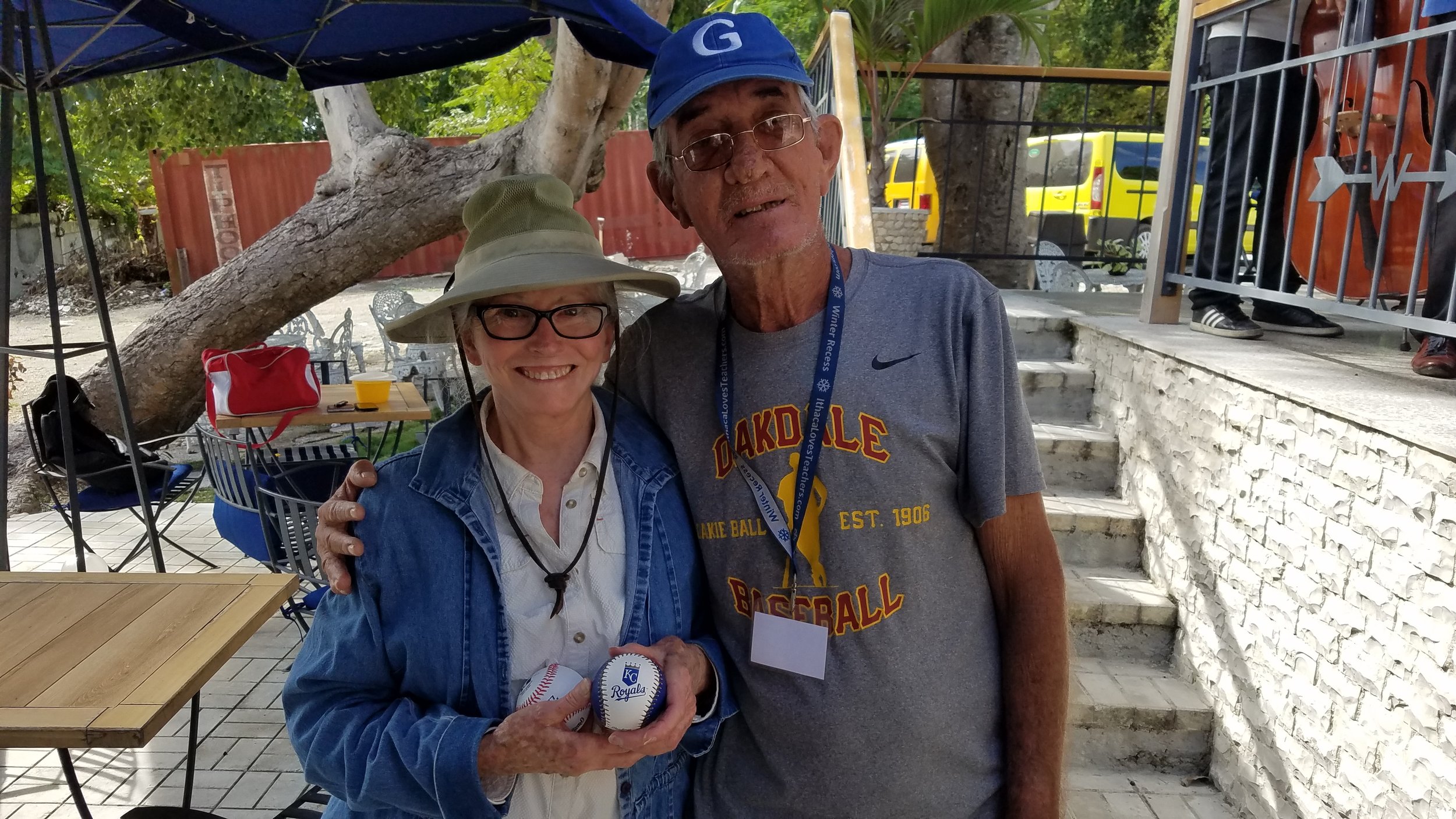

Every day in and around our international Hemingway conference has brought moments of enlightenment, delight and discovery. Friday began with a debate over whether and how the Soviet Union tried to lure Hemingway into its world as a propaganda tool. He would've preferred to be paid royalties for several Russian translations, but significantly rebuffed a royalty offer (this was Cold War era) by saying (in the letter posted below) he wouldn't accept unless Soviets paid all American authors what they were owed. Also in panels: Carl Eby's great exploration of the Basque landscape and mood that was mostly shorn out of the shrunken published edition of The Garden of Eden. Argentinian Hemingway scholar Ricardo Koon also detailed EH's Basque connections in Spain and Cuba. His photos included one shot of EH and Lauren Bacall outside the Carlton Hotel, where we've been staying and conferencing this week. We took an afternoon excursion to the Guggenheim Bilbao, which I'll post separately. The evening was capped by a wonderful spread of food along with music by a Dutch singer-songwriter who recorded a song cycle inspired by EH's first story collection, In Our Time. The Hemingway Society.

***

Bilbao afternoon. Calatrava, et al. River walk. Great Gehry. RIP Richard Serra. Oldenburg surprise. The damn Puppy love.

Richard Serra at the Guggenheim Bilbao

Sunday, July 21

Valerie Hemingway, then and now (with Jerry Kennedy)

Salud and feliz cumpleaños for Ernest Hemingway's 125th birthday (July 21). Our Hemingway Society conference concluded last night with a banquet, vino and long goodbys to friends. During the day we heard a stimulating and important panel on race, racism and related problems in teaching Hemingway in the current environment. There was a panel on modernism and the avant-garde. Our friend Rachel Neikirk guided us to country and Americana music inspired by EH (check out Turnpike Troubadours' latest record: A Cat in the Rain). And Valerie Hemingway recounted traveling Spain with EH in 1959, including an epic 60th birthday party. Now we'll take a quick trip to Gernika today, spend a bit more time with friends tonight in Bilbao, then off to Portugal.

Monday, July 22

Full-scale ceramic tile replica of Picasso’s epic painting, in Guernica/Gernika.

At the risk of over-sharing: Our last day in Bilbao included a day-trip to Gernika, site of the horrific Nazi bombing of innocents during the Spanish Civil War, 1937, and subject of the epic Picasso canvas. The town mounted a mosaic tile replica of the painting and a display of photos in the civic plaza outside a Peace Museum. Our guided excursion included a stop in Mundaka, a onetime whaling village now overrun by surfers and summer tourists. There's local opposition to the Guggenheim Foundation, which wants to open yet another art museum adjacent to a nature preserve a mere 35 kilometers or so from the big one in Bilbao. We also witnessed a protest moment having to do with improving the local bus service. Our tour also included a great recap of Basque history and a grueling hike to a church high atop an island mountain, San Juan de Gaztelugatxe (below). The many pilgrims here might have had an interest in St. John, but little did I know of the scenic connection to "Game of Thrones." Gorgeous coastal scenery. And off in the distance, the remains of a never deployed nuclear power plant, halted after an eruption of murderous Basque terrorism in the early 1980s.

Thurday, July 25

Porto is a gritty, dense, and scenic historic city with winding, narrow, and steep streets that might put you in mind of parts of San Francisco. We've had good and great food, and a long, rewarding excursion to the Douro wine valley, including a breezy jaunt on the river (will post those photos later). But the absolute discovery for us was the Serralves Foundation's Contemporary Art Museum. Yasoi Kusama is everywhere, but here we saw a career-spanning survey, including many early works we'd never seen. Other exhibits ranged from local radical history to up-to-the-minute abstraction and politically charged art. A sculpture park with major names (Eliasson, Kapoor, Oldenburg, Serra) and a satellite building in an art deco mansion featured gay-themed work of an art duo, including an installation that evoked Kansas. The main building's architect was unknown to me, but Álvaro Siza turns out to be a giant. The museum (originally opened in 2005) unveiled a new wing also by him late last year. The sleek addition includes a huge exhibit, sprawling through five rooms, of Siza’s archives and models. Outstanding. And now reading a book of Siza's essays. The journey continues.

Saturday, July 27

Winding down our three days in Lisbon. The fish was fine. As was the fado. Our new-found interest in the Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza got a serendipitous boost in an exhibit at the Gulbenkian Museum. And how did we not know that there was a Banksy Museum here, a commercial venture celebrating the subversive street artist. I went to the Contemporary Art Museum/CCB while my traveling companions went shopping. Very good collection of 20th-century isms, a show featuring the nature-grounded work of a female Bangladeshi architect, Marina Tabassum, and the main attraction (for me): "Evidence," a cosmic, earth and sun reverent soundscape and multi-media exhibit co-created by Patti Smith. Tough to explain, but it was suitably dreamy and mesmerizing.

At Fado au Carmo—Cláudia Picado with Luís Guerreiro (guitarra) and Alexandre Silva; my video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFk6HVnVbBs