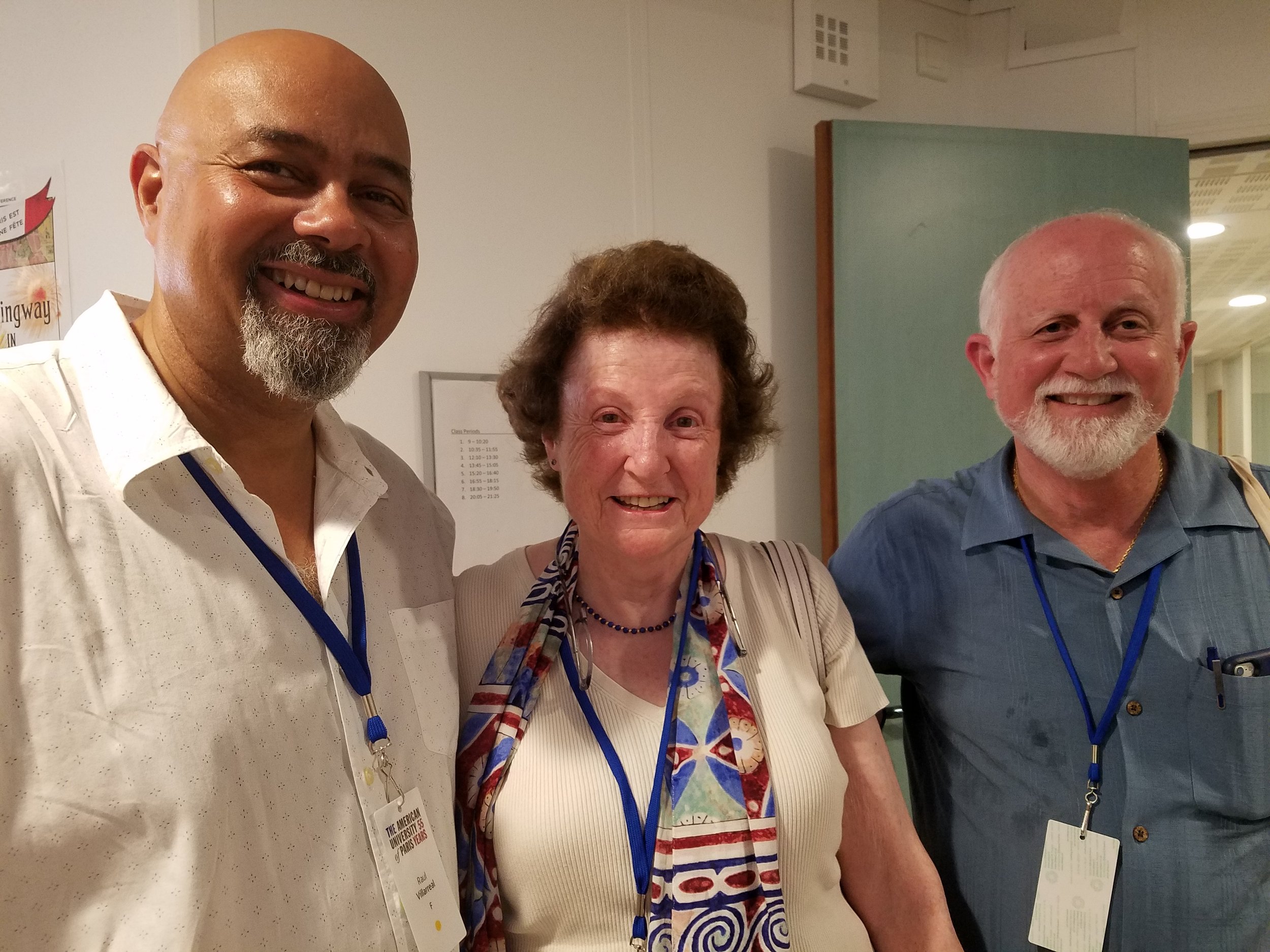

I just got the horrible news that our friend Raul Villarreal (left above), painter, traveler, and bon vivant, has died after a heart attack last night. We've gotten to know Raul in recent years in #Hemingway circles. Spent time with him last year in Paris, where the photo was taken, and then a week in Havana with him and Mike Curry (right) in December. Raul and Mike, colleagues at Santa Fe College in Gainesville, Fla., have been showing a documentary they produced about Hemingway, Cuba and Key West, which features interviews with Valerie Hemingway (center) and others. Raul came to the U.S. from Cuba as a boy. His father had been Hemingway's major domo, the man who ran the Finca Vigia household outside Havana, for several years and then, after the Cuban takeover, managed the house as the Hemingway Museum. Raul published a book about his father, "Hemingway's Cuban Son," a decade ago. It was an honor to meet Rene, Raul's father, back then, and of course to have known Raul's large spirit ever since. Carol Zastoupil showed her Cuba paintings at an exhibit Raul curated a couple of years ago at Santa Fe College. And I hooked Raul up a few years back with Robert Stewart at New Letters, who published some of his paintings in an issue with a section on Cuba. This is just so depressing. RIP, hermano. Abrazos to Rita and all who knew him.

cuba

Remembering Fico: The Hemingway Trail in Cuba Loses Another Direct Connection

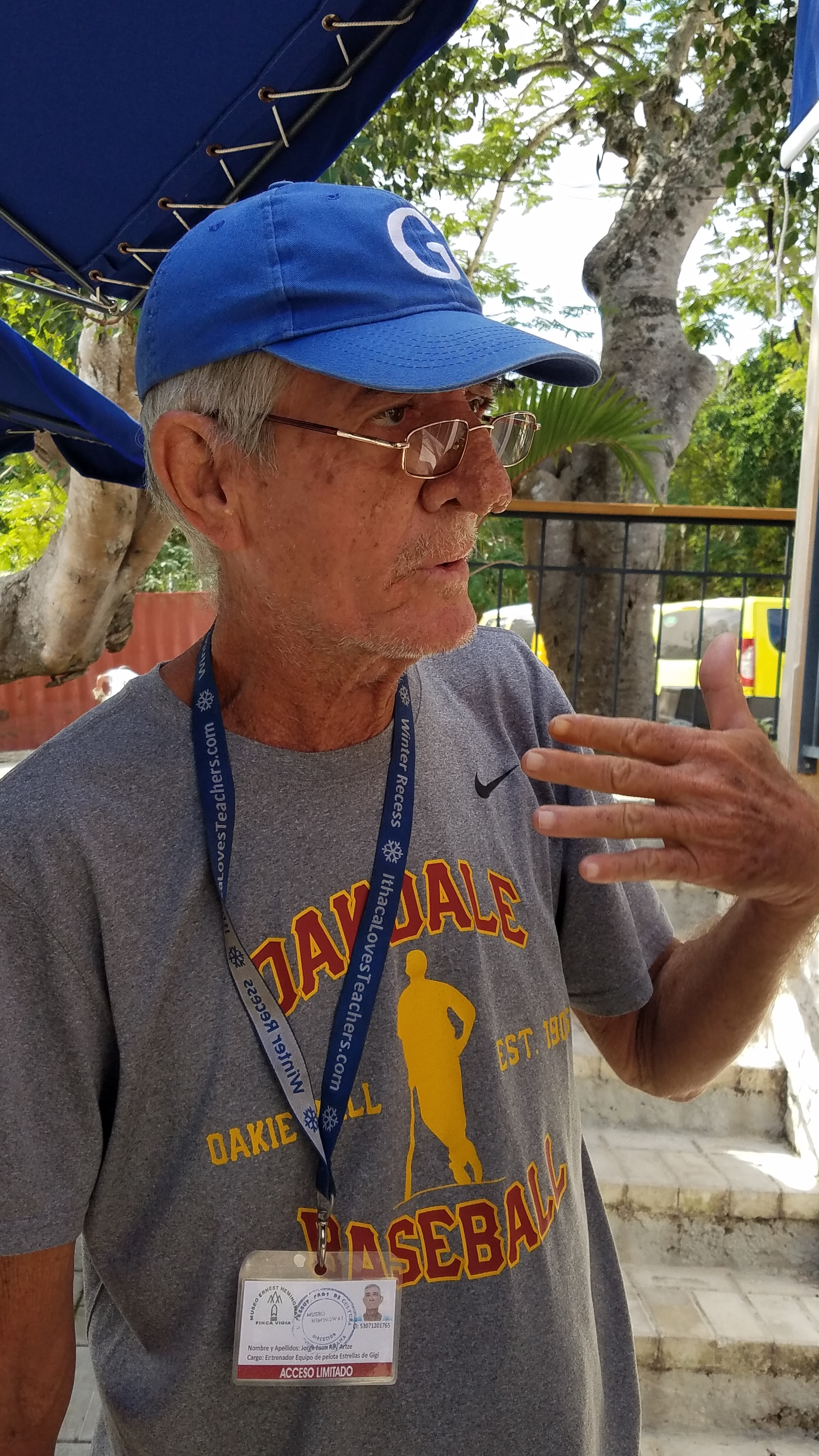

While we were in Cuba last month, we learned of the recent death of Alberto "Fico" Ramos. Fico is well-known in Hemingway circles, because he was one of the original members of the baseball team that the writer created for his son Gregory after taking up residence outside Havana in the early 1940s. The team was called the Gigi Stars, Gigi being the 10-year-old (or so) Gregory’s nickname. Fico later became chef at the Hemingway house, known as the Finca Vigia, or Lookout Farm. The house stands high on a hilltop above San Francisco de Paula, a village about a dozen miles southeast of Havana. The Cuban government has owned the house since the Hemingways left in 1960 and now operates it as the Museo Ernest Hemingway.

We met Fico on our first trip to Cuba, in 2003, and I sat in on an interview session on the grounds of the Finca, sitting by the drained pool, where I took this photo. I remember Fico as extremely personable and eager to share stories of life around the Hemingways. Our friend Raul Villareal, with whom we spent a week in Havana in December, confirmed Fico’s death the first week of December. “He was able to see his daughter who came in from Miami and I was told that he left us peacefully in her company,” Raul told us in an email. Fico in fact worked with Raul’s father, René Villareal, who ran the Hemingway household in the 1950s and oversaw its preservation after Hemingway’s suicide in 1961. “I was very sad to hear the news,” Raul added. “(W)e lost one of the few remaining Cubans who knew and worked for Hemingway.”

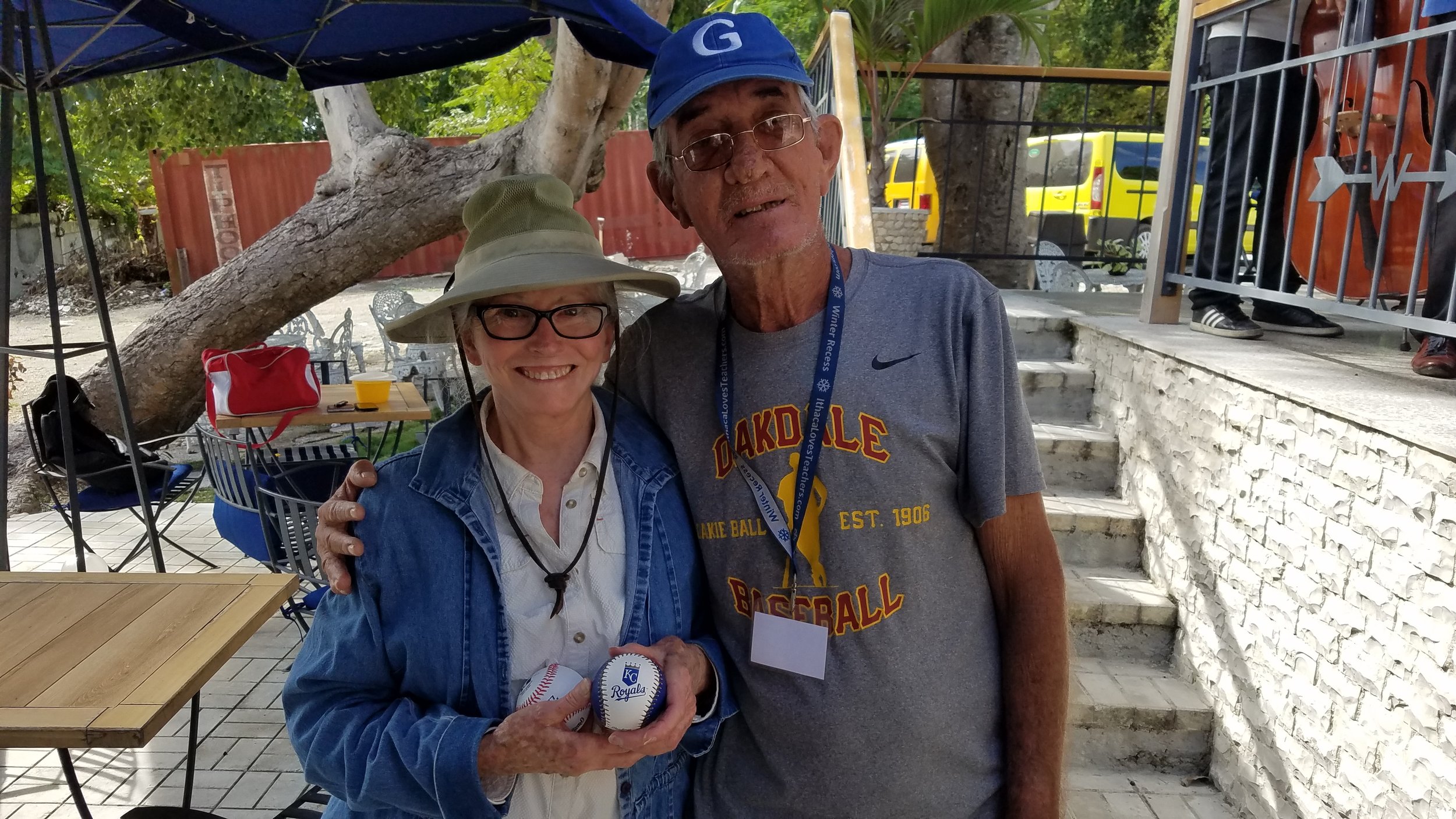

To bring the story full baseball circle: On our return visit to the Finca Vigia in December, we happened to meet Jorge Juan Rey Artze, who for 10 years has coached a youth baseball team in the surrounding village of San Francisco de Paula. Carol Zastoupil thus was able to continue her mission to deliver baseballs to young Cubans. We’ve often seen kids swinging crude bats against rocks in the street, so she has taken the lead in loading her bag with baseballs. (I pack a few sets of guitar strings to hand out.) A couple of years ago, we stopped to watch a youth team practice in Guantanamo City and shared a bunch of balls with them, leading to a team picture and much good cheer.

A sad postscript: Our friend Raul Villareal died unexpectedly of a heart attack not long after I wrote this item about Ficto and just a few months after our trip to Cuba in December 2018. You’ll find a tribute to Raul elsewhere on this blog.

In Key West, Exploring the Many Alluring Worlds of Caribbean Writers

An uncanny bit of synchronicity lit a fuse underneath the recent Key West Literary Seminar. The seminar, devoted this year to “Writers of the Caribbean,” kicked off in early January on the very day that Washington D.C. fell victim to reports that the alleged leader of the free world had disparaged various brown-skinned homelands as “shithole countries.” Edwidge Danticat, a New Yorker who writes frankly and plaintively of her native Haiti, addressed the matter head on from the seminar stage. The first words out of her mouth on a panel on “unpacking paradise” the next day: “I’m apparently from a shithole country … so we never had that paradise.” Others throughout the weekend echoed her disgust -- sometimes subtly or ironically, sometimes quite openly. But the subtext certainly heightened the seminar’s great opportunity, which for me was to discover a vibrant geography of literature with which I’d had far too little experience.

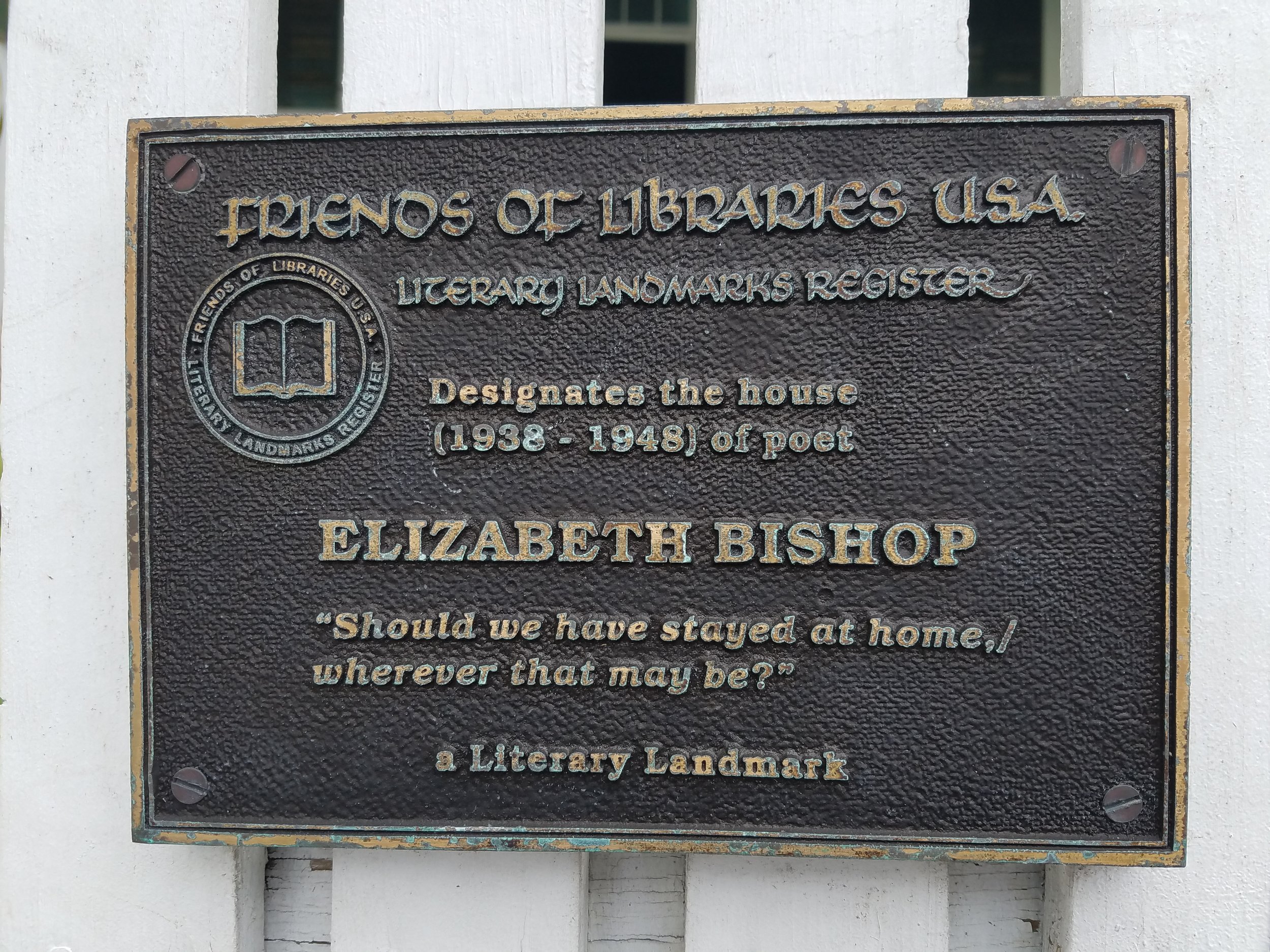

The spirit of Derek Walcott, the great poet from the island of St. Lucia who died last March, infused the seminar. Elizabeth Bishop, who lived in Key West in the 1930s and ‘40s, was cited frequently as well. I’d been reading some of Walcott’s long-line poems recently, and I flashed on my only personal encounter with him. It was 1999 in Boston – he was teaching at Boston University at the time – and he was one of the many global writers invited to speak and sometimes argue during an event commemorating Ernest Hemingway’s 100th birthday. Walcott was somewhat dismissive of the worst of Hemingway’s tendencies but gave him credit for infusing some of his prose with the sound of fine poetry. The examples he read, as I recall, were convincing.

Hemingway’s name barely came up during this Key West seminar; I’m sure if it had, the writers who identify as Caribbean would not have been overly kind to the privileged American who made Cuba his home for two decades. Then again, the great Cuban writer Leonardo Padura, another big-name seminar participant, has acknowledged his debt to Hemingway. (In Cuba, he said, everyone wants to plagiarize Hemingway.) The outsized appetites of Padura’s recurring character, the police detective Mario Conde, certainly parallel Hemingway’s at times, though Padura’s prose, in its English translations, tends more towards lush expressionism, as if he were a painter with an overloaded brush, rather than Papa-style restraint. Padura still lives in Havana, where he manages to walk the fine artistic line that criticizes by slant and irony and thus allows him a certain protected status as well as the ability to publish outside Cuba. Nevertheless his account of the brutally unfair publishing system in Cuba was enlightening. A writer spends three years working on a novel and gets about $250 from a Cuban publisher, he said: “Being a writer in Cuba is practically an act of faith.” (The seminar happened to align with an art exhibit by the youngish Abel Barroso, a highly ironic and talented Cuban who also has earned the chance to show and sell overseas. We had met Barroso in his home during an art tour five years ago, and it was rewarding to see and hear him, during an opening event, surrounded by large and memorable pieces of his work.)

Caryl Phillips delivered one of the major highlights of the seminar when he read from a forthcoming novel, A View of the Empire at Sunset. In it, he imagines an episode from the life of the complicated writer Jean Rhys (Wide Sargasso Sea) as she returns to the island of Dominica, where she’d grown up before setting off for her Bohemian existence in London, Paris and elsewhere. Little is known about her six weeks on the ground there, which gave Phillips his opening for invention, he conceded. His excerpt was stunning, and I’m sure I was not the only listener planning to snatch the novel up when it comes out in May. Phillips, another displaced islander, also impressed with a keynote essay at one evening’s tribute to Walcott. Phillips spoke about Walcott’s early experience in New York, amidst the theater world in 1958-59. It was a period of mostly unhappiness. Walcott was largely alone, ignored by the literary elite and too disciplined for the Beat crowd, Phillips noted. He cut his fellowship short. “In New York,” Phillips said of Walcott, “by learning what he wasn’t, he learned what he was – a West Indian.” Phillips’s rather downbeat portrait prompted the publisher Jonathan Galassi to lament the next day that Phillips had left out Walcott’s later successes. Well, sure, but it bears reminding that true achievement often follows failure, and the status of a Caribbean outsider in New York’s high-brow white culture was a point not lost on the rest of us.

Jamaica Kincaid shared a typically circuitous essay on the subject of cultural appropriation. She began with an image of Dana Schutz's controversial painting of the embalmed mangled face of Emmett Till, and came down on the side of chilling-out about it. "All that we make belongs to all of us," Kincaid said. "The only thing we can't take from us is freedom."

Along with the superstar presenters such as Phillips, Danticat, Padura, and Kincaid, the seminar gave voice to a slew of younger writers. I’d read Teju Cole (Open City and some of his writing on photography) and Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, but had not yet encountered the likes of Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Kei Miller, Ishion Hutchinson (National Book Critics Circle winner in poetry for 2016), Nicole Dennis-Benn, Andre Alexis, or Tiphanie Yanique. Each had a unique perspective on where he or she had come from (Antigua, Jamaica, Trinidad, U.S. Virgin Islands) and what informs the poetry and prose. I read one of Hutchinson’s book’s on the airplane heading home. Rowan Ricardo Phillips began his wide-ranging, beautifully rendered keynote talk ("I Who Have No Weapon But Poetry") with a reading from Emily Wilson's new translation of The Odyssey (note to self: must read). He read the chapter where Odysseus confronts the Cyclops and tricks the sleeping giant with the "No Man maneuver," suggesting perhaps the potential power of a Caribbean identity as No Man. (Read Polyphemus as the U.S., or the current POTUS?) And it was a subtle prelude to Phillips's later acknowledgment of Walcott, whose masterwork is the epic Omeros. (Time to revisit that, too, and to read Rowan Phillips's books as well.)

Marlon James’s novel is steeped in Jamaican patois. He had trouble writing it early on, almost defeated by the task of juggling its multiple voices, he said, until someone suggested he read William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. I also appreciated his shout-out to Jessica Hagedorn’s novel Dogeaters (1990), which I’d admired years ago, as the “greatest novel about Jamaica” even though it’s set in the Philippines. I never got a chance to suggest to James that A Brief History of Seven Killings, winner of a Man Booker prize, reminded me a bit of Richard Price’s streetwise novel of young drug dealers, Clockers, but it did. I’ll look forward to a forthcoming TV series based on James’s big novel. James is an executive producer and one of five writers working on scripts for the 10 episodes (for Amazon). More power to him.

All of this literary immersion, of course, takes place deep in the heart of Duval Street, the spine of Key West’s daily carnival of unleashed hedonism. Key West is slowly recovering from the hurricane that ravaged the middle Keys; though it suffered relatively little damage, Key West is still affected by misperceptions, and the tourist business did not yet seem fully up to speed. Some street performers certainly were having a tough time of it. “These literary fuckers aren’t giving anything up,” said one noodling flutist. He was crouched on a sidewalk down the block from the San Carlos Institute, a historic Cuban building that houses the annual seminar.

I felt rather lucky landing a place in the seminar, which has been going on for 36 years. The seminar sells out quickly and seems to have become a literary playground for Key West’s high society. (Next year: Margaret Atwood!) Oh well; I can think of worse places to take a winter vacation. And the chance to expand my literary boundaries and add to my must-read piles seems kind of worth it.