The Kansas City Star’s Judy Thomas wrote this week about the death of Leonard Zeskind, a Kansas Citian committed to researching and uncovering the many tendrils of white nationalism in the U.S. His landmark book on the project was one of hundreds recently purged from the library at the U.S. Naval Academy by the reckless administration, Judy reported. In 2009, I wrote about the book upon its release, and reading about it again, in this fraught moment of authoritarian and right-wing fervor, speaks to its utter timeliness and timelessness. In visits with Zeskind at his office at the time, a labyrinthine lair lined with file cabinets, he displayed both a sly sense of humor and utter seriousness about his work. In one moment, he beseeched me to aim a bottle of lubricant into his eyes. That was a first in my newspaper career. The story below first appeared on page 1 of The Kansas City Star on May 18, 2009.

books

The Year in Books: Recapping Some Reading from 2024

By STEVE PAUL

(c) 2024

Belatedly posting some notes about memorable books from year now past. Somewhere around Thanksgiving I returned to KCUR’s “Up-to-Date” with Steve Kraske to discuss some of my favorite reads of the year. I’m posting a few of my notes here, followed by lists of other books I spent quality time with.

Here are the highlights from the radio show:

Percival Everett: James (Doubleday). Winner of the National Book Award and other honors this year, Everett’s novel retells the story of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn through the consciousness of that classic’s Black character, known as Jim. Everett’s James is smart, literate, philosophical, courageous, cagey, and his story of escape, survival, adventure, danger, and the complicated bonds with Huck is unforgettable. I listened to the audio version of the novel and was riveted from beginning to end.

Donna Seaman: River of Books: A Life in Reading (Ode Books/Seminary Co-op). Not just because Donna Seaman is a friend, her memoir of a lifetime devotion to the essential act of reading is a delightful and winning procession of connected essays. A longtime staffer at the American Library Association’s advance-review journal, Booklist, she has recently ascended to editor-in-chief. Her story of a rebellious, smart childhood in rough-edged Poughkeepsie, New York, being the loving daughter of loving and reading parents, includes a year or so in Kansas City in the 1970s when she attended the Kansas City Art Institute. The book is infused with literary tributes, artistic and creative impulses, and despite episodes of personal loss, a spirit of generosity, love of the natural world, and human fellowship. Anyone who loves books and identifies as a chronic reader will recognize a kindred spirit and compare influences and reading lists with those that Seaman shares.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde (Farrar Straus Giroux). This deeply imagined and unconventionally constructed biography tells a compelling life story, tracing Audre Lorde’s journey from tough and emotionally challenging childhood to her status as beloved poet, lesbian activist, and spiritual thinker. Gumbs brings a poetic eye and empathetic sensibility, especially toward Lorde’s themes exploring science, nature and the physical and metaphorical universe.

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, edited by Denise Murrell (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press). In the category of art and “coffee-table” books, this is the huge and handsome catalogue of a major retrospective exhibit that I saw earlier this year at the Met in New York. The sheer variety of style, craft, imagery, and narrative content of these works proves how far from monolithic the creative movement we call the Harlem Renaissance really was. There’s intimate portraiture, vibrant street scenes, abstract collage, and stunning representations of the range of humanity that made up the African American experience in the 1930s and beyond. One particular revelation, for me, were the lovely portraits and lively, boozy social canvases by Archibald Motley. Another involved dwelling on a familiar mural by Aaron Douglas and realizing how it resonated with the kind of political engagement to be found in Picasso’s “Guernica.” This book is filled with insightful scholarly essays that provide broad context and detailed focus on many of the individual art works.

Wright Thompson: The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi (Penguin Press). Extraordinary and riveting narrative that recounts all the threads of American history that led to the torture and killing of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy, by white men in 1955. This essentially is the biography of a place, a small patch of the Mississippi Delta, which also happens to contain the family home of the author. Thompson, an award winning writer who once wrote sports stories at the Kansas City Star, performed an enormous amount of research as he interweaves his own story and his quest through deep history and the murky legacies of the civil rights-era tragedy that still resonates today.

Samantha Harvey: Orbital (Atlantic Monthly Press). Recent winner of the Booker Prize, this short novel becomes a meditation on human existence, prompted by the narrative’s setting inside the minds and lives of six International Space Station occupants as they speed around the planet. It’s a lyrical and evocative read, though one that some readers might find to be periodically precious. This was another book that I absorbed by listening, an audible experience that was uplifting, cosmic and often hypnotic.

Rachel Kushner: Creation Lake (Scribner). There’s an unusual setup as a mysterious central character, an American woman who may or may not be named Sadie Smith, wangles her way into a collective of French environmentalist rebels. A cult leader’s lectures on human history and the legacy of Neanderthal life in the workings of the modern world give the novel some intellectual heft. The main character’s relationships, sexual drive, and subterfuges provide loads of tension and propulsion as the novel unfolds.

Much of my reading these days involves biography, given my involvement in Biographers International Org. Early in 2024 I caught up with the five finalists for the 2024 Plutarch Award, honoring the best of the prevous year: Each of these five books took a different approach to biography, illustrating, for me, the great range that the craft of biography (as distinguished from autobiography and memoir) spans today.

Jonathan Eig, King: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Howard Fishman, To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse (Dutton)

Lisa M. Hamilton, The Hungry Season: A Journey of War, Love, and Survival (Little, Brown and Company)

Prudence Peiffer, The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever (Harper)

And the Plutarch winner: Yepoka Yeebo, Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington, and Swindled the World (Bloomsbury)

More recent reading and biography titles to come.

From the Archives: Reading and Interviewing Margaret Atwood, 1993-2022

By STEVE PAUL

With Margaret Atwood coming to Kansas City soon for a library talk (Sept. 24), I thought I’d dredge up a couple of related old pieces. I had the opportunity to meet and interview Atwood in 1993 at the annual American Booksellers Association confab (now Book Expo) in Miami. Her novel The Robber Bride was coming out that fall and her publisher had sent me an early copy of the book—so-called advance review copies were not yet ready, so they sent me a dupe of the typed manuscript. I’ll concede that my reading of Atwood was rather conventional if not underwhelming from today’s perspective. Then again, the interview with her remains enlightening.

In talking about the essential status of mythology in contemporary story-telling, one of the driving forces of her writing, she illustrated:

“One of the founding stories of U.S. culture is the biblical quotation ‘by their fruits they shall know them.’ It was originally intended spiritually—you know good people by how they behave. But it was interpreted by the Puritans to mean you can tell good people by how rich they are, which is with us today. It underlies so much literature in this culture—the idea of sin and redemption.”

Find reproductions of the two pieces, published Nov. 14, 1993 in the Kansas City Star, in three images below.

In more recent years, I had the pleasure of encountering Atwood at the Key West Literary Seminar. She spoke again about myth and fable. In my memory she talked about the movie “Aquaman” as a product of myth. The movie had just recently come out and she suggested that she watched it so we wouldn’t have to. (I still haven’t gotten around to it.) One morning in Key West, we ended up at a Duval Street CVS at the same time, where I met her husband, the writer Graeme Gibson. He would die just months later, as I recall.

Atwood happens to make a cameo appearance in my biography-in-progress of William Stafford. This goes back a ways to Atwood’s years as an emerging poet and fiction writer (her first novel was published in 1969). Shortly after being named Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress for 1970-71, what we now call the U.S. Poet Laureate, Stafford put Atwood’s name on a short list of writers he would like to host during his tenure. He wanted to make sure women were represented on what was very much a male-dominated field. Sure enough, one of the first reading programs Stafford hosted in the fall of 1970 brought together Atwood and Galway Kinnell.

In 2022 I wrote to Atwood to see what she might recall of the event and/or Stafford. She kindly replied, hand-writing her response on my original letter and sending it back to me:

“I was 30! A very minor figure! …I love Wm Stafford’s poetry in book form—but he was a big cheese and I was a very small cheeselet.”

And here’s a blog bonus: An audio recording of the reading can be found at the Library of Congress website. Find it here and enjoy:

Miró Foundation

Travels: Spain and Portugal

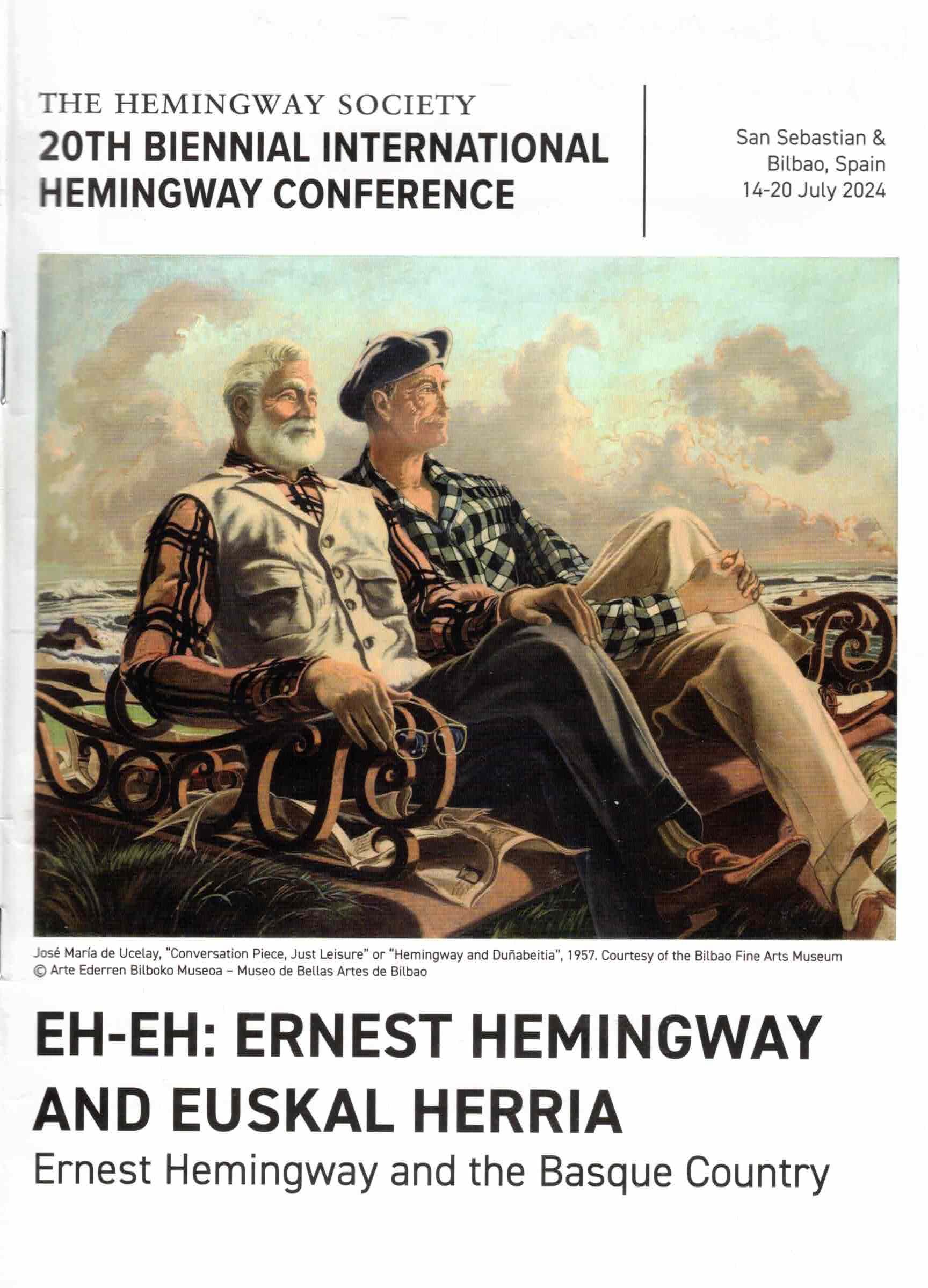

Gathering some of the notes and photos I posted on FB during our excursion. The main event was the 20th Biennial International Ernest Hemingway Society Conference in San Sebastián and Bilbao, Spain, or Basque Country, Euskal Herria as the locals would rather hear it. I’ll aim to expand and revise as I proceed, so this post may evolve over time, especially as I look deeper and more critically at photos.

Wednesday, July 10, Barcelona

Didn't take long to absorb a new appreciation for Joan Miró at his @fundaciomiro in Barcelona. What a gorgeous spread of the surreal spirit. First taste of Barcelona after a long travel day was a pretty fine Italian sandwich from a place near our hotel. Later, for early din, we had what might be the first of a long series of tapas on this journey, with a Vermut aperitif and a glass of Spanish red. First Gaudi sighting: the Guell Palace. No encounters with anti-tourist protestors, but the place and its narrow alleyways are certainly abuzz with people. You can hardly avoid La Rambla, the main pedestrian thoroughfare. Struck me something like Duval Street on steroids. IYKYK. Closed out the day in the hotel bar watching England shock the Dutch in the Euro.

Thursday, July 11, Barcelona

Gaudi: Casa Battló

It's rather impressive to see how much the experience of Barcelona involves the architecture of Antoni Gaudi. The city's ancient stone bones share the spotlight with Gaudi's pop-eyed, playful, curvy, and sensuous inventions. There's of course the Sagrada Familia, still under construction but nearing completion after all these years. We got immersed in Casa Battló, one of the most brilliant architectural redos you'll ever see. The tour experience (jammed with people) begins and ends with contemporary psychedelic dreamscapes. The latter is an AI creation by Refik Anadol, whose earlier deployment of collection data turned a huge wall at the Museum of Modern Art in NY into a plasmatic performance of bursting color.

Friday, July 12, Barcelona

Given we'll soon be immersed in Hemingway world, I was happy (not the right word) to trip upon an exhibit of art and the Spanish Civil War at the Museu Nacional D'Art de Catalunya in Barcelona (below)). Stunning and painful images of all kinds, including another Miró.

Sunday, July 14, San Sebastián

Before the opening of our Hemingway conference tonight in San Sebastian (Donostia, as Basque people call it), we went to a civic cultural center to see an exhibit of Hemingway's long experience with Basque culture, people and places. Saw some images and info I was unfamiliar with, so enlightenment happened.

Tuesday, July 16, San Sebastián

The 20th International Ernest Hemingway Society enters its third day later today in San Sebastián, Spain. On Monday I moderated one panel and gave a paper (on the short story "After the Storm"), so now my "work" is done. It's great to be among old and new friends, and to marvel at all the good research being done by scholars and writers in various fields (marine biology, geography, journalism, fiction, poetry, dance, art, food) and from all over: Spain, of course, U.K., Georgia (republic), Serbia, Japan, France, U.S. and Canada. And, in San Sebastian, a scenic, seemingly prosperous place, some of the world's best eating beckons day and night. Last night we elbowed our way into a pintxos bar that, on good authority, was a favorite of Anthony Bourdain's: a bacalao dish and lengua en salsa were delicioso. And the vermut (on the rocks, with an orange slice, which we've been sampling nightly since we started in Barcelona) had a distinctive essence of thyme in the nose. Will have to go back to view the bottle. More panels today and dinner honoring our young scholarship recipients at a cidery.

***

Elena Zolotariov (right) is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of London. We met in Wyoming a couple of years ago. She is the real deal and represents the future of Hemingway studies. She introduced me to two attendees from Georgia.

Wednesday, July 17

This morning we leave San Sebastián for Bilbao on a bus trip via a noted winery. Tuesday (I think it was) brought more deep dives at the Hemingway conference. We heard from the editorial team at the Hemingway Letters Project, which has just produced volume 6 of his collected letters, another big book covering less than two years, 1934-36. Other papers we heard examined aspects of dance, prompted largely by The Sun Also Rises (glad I reread it on the flight crossing the pond a week ago), Hemingway on film (especially as used by teachers), as well as the work of Martha Gellhorn, the writer and unhappy survivor of EH's marriage No. 3. In town we returned to the little Haizea Bar for breakfast and wound up the evening at a cidery for a dinner and drinkfest honoring the young recipients of Hemingway Society travel and research grants.

I was honored to be included on a panel with Japanese scholars Kaori Fairbanks and Hideo Yanagisawa, with whom I've been acquainted for many years.

***

Wine was the theme of our excursion toward Bilbao on Wednesday. A visit to the Marques de Riscal wine estate, where Frank Gehry built a hotel expansion in 2006 (inset; no time to look inside, so this was just a tease before our visit to the Guggenheim Bilbao on Friday.). A fabulous restaurant lunch, with generous pours of bianco (Verdejo from the Ribera de Rueda) and the Rioja region's predominant tinto (Tempranillo). A stroll through the walled village of Laguardia, including a guided tour of a wine producer's cave inside the town's medieval system of elaborate tunnels.

Thursday, July 18

A musical interlude for my friends in The Hemingway Society: Today at the proceedings of our international conference in Bilbao, Spain, one session served as a tribute to two recently deceased Hemingway scholars--Donald Junkins and H.R. "Stoney" Stoneback. Mike Roos sang his song "The Unfinished Church," which draws from scenes in The Sun Also Rises and was encouraged by Stoney. In addition, two former students of Stoney at New Paltz, Alex Pennisi and Joe Curra, played the late Jerry Jeff Walker's great early road song about our friend Stoney. I once interviewed Walker and got to discuss our mutual connection with Stoney. Always loved this tune, even before I knew Stoney. Both vids on my YT site.

https://youtu.be/CbqhADOOZ1M?si=MBc7SfzsiPC3715X

https://youtu.be/Gs-BXK7u6KE?si=fbw4UfW-w42c54zq

***

First glimpse last night of Gehry's Guggenheim in Bilbao. We'll spend time there later today. At Thursday's Hemingway conference sessions: Linda Patterson Miller (l), author of the landmark essay "Why I love Papa," talked about rattling the male scholars' cage back in the 1980s, helping to open Hemingway studies not only to female scholars but also to female and personal voices in writing (including Ann Putnam at right). This led to lively discussion of the longstanding tussle in academia over first-person prose and memoir. This is somewhat similar to what we talk about in my overlapping world of biography, the hybridizing of the craft with memoir. Big topic, long story for later. With the public domaining of The Sun Also Rises, we heard from four editors who have produced four(!) distinct new editions of EH's first novel, one for public consumption, three aimed at classroom use. The projected final volume of the Hemingway Letters, expected to be pubbed in the 1940s, is being worked on now because we still have Valerie Hemingway in our midst, and she was right there as EH's secretary, taking his dictation for most letters in 1959 till the end, in '61. Jerry Kennedy had a brilliant take on those last years, including the travails of The Dangerous Summer, and Michael von Cannon described the editing process and other discoveries for Vol. 17. Later: a pelota (jai alai) demonstration, pintxos and drinks with friends and nightcap with a good crowd at the hotel lounge, conveniently located down the hall from our room.

Friday, July 19

Every day in and around our international Hemingway conference has brought moments of enlightenment, delight and discovery. Friday began with a debate over whether and how the Soviet Union tried to lure Hemingway into its world as a propaganda tool. He would've preferred to be paid royalties for several Russian translations, but significantly rebuffed a royalty offer (this was Cold War era) by saying (in the letter posted below) he wouldn't accept unless Soviets paid all American authors what they were owed. Also in panels: Carl Eby's great exploration of the Basque landscape and mood that was mostly shorn out of the shrunken published edition of The Garden of Eden. Argentinian Hemingway scholar Ricardo Koon also detailed EH's Basque connections in Spain and Cuba. His photos included one shot of EH and Lauren Bacall outside the Carlton Hotel, where we've been staying and conferencing this week. We took an afternoon excursion to the Guggenheim Bilbao, which I'll post separately. The evening was capped by a wonderful spread of food along with music by a Dutch singer-songwriter who recorded a song cycle inspired by EH's first story collection, In Our Time. The Hemingway Society.

***

Bilbao afternoon. Calatrava, et al. River walk. Great Gehry. RIP Richard Serra. Oldenburg surprise. The damn Puppy love.

Richard Serra at the Guggenheim Bilbao

Sunday, July 21

Valerie Hemingway, then and now (with Jerry Kennedy)

Salud and feliz cumpleaños for Ernest Hemingway's 125th birthday (July 21). Our Hemingway Society conference concluded last night with a banquet, vino and long goodbys to friends. During the day we heard a stimulating and important panel on race, racism and related problems in teaching Hemingway in the current environment. There was a panel on modernism and the avant-garde. Our friend Rachel Neikirk guided us to country and Americana music inspired by EH (check out Turnpike Troubadours' latest record: A Cat in the Rain). And Valerie Hemingway recounted traveling Spain with EH in 1959, including an epic 60th birthday party. Now we'll take a quick trip to Gernika today, spend a bit more time with friends tonight in Bilbao, then off to Portugal.

Monday, July 22

Full-scale ceramic tile replica of Picasso’s epic painting, in Guernica/Gernika.

At the risk of over-sharing: Our last day in Bilbao included a day-trip to Gernika, site of the horrific Nazi bombing of innocents during the Spanish Civil War, 1937, and subject of the epic Picasso canvas. The town mounted a mosaic tile replica of the painting and a display of photos in the civic plaza outside a Peace Museum. Our guided excursion included a stop in Mundaka, a onetime whaling village now overrun by surfers and summer tourists. There's local opposition to the Guggenheim Foundation, which wants to open yet another art museum adjacent to a nature preserve a mere 35 kilometers or so from the big one in Bilbao. We also witnessed a protest moment having to do with improving the local bus service. Our tour also included a great recap of Basque history and a grueling hike to a church high atop an island mountain, San Juan de Gaztelugatxe (below). The many pilgrims here might have had an interest in St. John, but little did I know of the scenic connection to "Game of Thrones." Gorgeous coastal scenery. And off in the distance, the remains of a never deployed nuclear power plant, halted after an eruption of murderous Basque terrorism in the early 1980s.

Thurday, July 25

Porto is a gritty, dense, and scenic historic city with winding, narrow, and steep streets that might put you in mind of parts of San Francisco. We've had good and great food, and a long, rewarding excursion to the Douro wine valley, including a breezy jaunt on the river (will post those photos later). But the absolute discovery for us was the Serralves Foundation's Contemporary Art Museum. Yasoi Kusama is everywhere, but here we saw a career-spanning survey, including many early works we'd never seen. Other exhibits ranged from local radical history to up-to-the-minute abstraction and politically charged art. A sculpture park with major names (Eliasson, Kapoor, Oldenburg, Serra) and a satellite building in an art deco mansion featured gay-themed work of an art duo, including an installation that evoked Kansas. The main building's architect was unknown to me, but Álvaro Siza turns out to be a giant. The museum (originally opened in 2005) unveiled a new wing also by him late last year. The sleek addition includes a huge exhibit, sprawling through five rooms, of Siza’s archives and models. Outstanding. And now reading a book of Siza's essays. The journey continues.

Saturday, July 27

Winding down our three days in Lisbon. The fish was fine. As was the fado. Our new-found interest in the Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza got a serendipitous boost in an exhibit at the Gulbenkian Museum. And how did we not know that there was a Banksy Museum here, a commercial venture celebrating the subversive street artist. I went to the Contemporary Art Museum/CCB while my traveling companions went shopping. Very good collection of 20th-century isms, a show featuring the nature-grounded work of a female Bangladeshi architect, Marina Tabassum, and the main attraction (for me): "Evidence," a cosmic, earth and sun reverent soundscape and multi-media exhibit co-created by Patti Smith. Tough to explain, but it was suitably dreamy and mesmerizing.

At Fado au Carmo—Cláudia Picado with Luís Guerreiro (guitarra) and Alexandre Silva; my video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFk6HVnVbBs

From the Archives: Stanley Crawford's 'Mayordomo'

I was saddened to learn of the recent deaths of two important New Mexico writers, N. Scott Momaday and Stanley Crawford. I never had the chance to meet Momaday though I certainly knew of his legacy as a voice of Native American culture. I did intersect with Crawford years ago and wrote about one of his New Mexico books. I’d only recently begun traveling to the Southwest and getting a handle on the interwoven cultures of the “Land of Enchantment.” Crawford’s Mayordomo was an enlightening guide to the complications of village life. This first appeared in the Kansas City Star in 1988.

From the Archives: Calvin Trillin Three Ways

One of Kansas City’s favorite literary native sons is coming back to town on a book tour soon. He’s touting a new collection of some of his classic magazine journalism, including landmark reporting on the Civil Rights movement of the early 1960s. It was some years later when Trillin’s “American Journal” reports began catching my eye in The New Yorker, and then a decade or so more when I began writing about Trillin during my days as Book Review Editor of The Kansas City Star.

I’ve dug deep into the files to unearth one of those book related stories, which included an interview in Trillin’s Greenwich Village pad.

Twice in the 2000s I managed to accompany Trillin on food tours of his beloved lower Manhattan, which turned me on to some of the more interesting corners of the village and Chinatown.

For now, I’m posting jpeg clippings. Hope that works for all.

Now, a food tour, 2005. My syndicated piece published in the Honolulu newspaper.

Seven years later, 2012, mostly new places, but some old favorites.

TABULA RASA, Volume 1, by John McPhee (Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Me and Johnny McPhee: A Book Review, etc.

By STEVE PAUL

(c) 2023

Something like almost 50 years ago, I was in Boston (actually, Newton) and staying in the third-floor guest room in a friend’s family’s Victorian house. I had some time to myself, and found on a table next to an easy chair a book I knew nothing about. It was called Oranges. The author was John McPhee, whom I had not yet had the pleasure of reading. I opened it. It was about oranges! And, strangely, seductively, on the very first page, McPhee performs a sequence of citric facts in a narrative dance that became instantly mesmerizing. I read the whole damn thing that weekend and became something of a McPhee disciple.

Years later, in the occasional class or workshop I led on non-fiction writing, I used the first chapter of Oranges as an example of the literature of fact. Some younger students didn’t get it, but maybe the problem was they didn’t get me or my class either.

A few years after reading Oranges, while early in my career as a daily journalist, I thought I ought to polish my resumé and, rather foolishly, enrolled in graduate school. In economics. The university department emphasized a discipline of social thought rather than mere numbers, and I’d enjoyed those studies as an undergrad. Bad move. When I pitched a paper proposal on an environmental issue relating to Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, the professor wanted to know what my sources were going to be. Well, there’s this great book about Alaska and the environment, Coming into the Country, by John McPhee (1976). Well, no, I was told; that’s just journalism and not good enough for graduate school. I made a feeble effort to gather some proper economic data. Then, essentially, I gave up and never finished the paper. Or graduate school.

As a journalist, my admiration for McPhee extended to a magazine project I organized—as an editor, not a writer—which borrowed from McPhee’s Encounters with the Archdruid (1971). One part of his story involved a rafting trip down the Colorado River alongside a federal land agency official and an outspoken environmentalist. The framing of McPhee’s three-part book made it a quasi-biography of David Brower, who would go on to prominently [found?] lead the Sierra Club. In our version of the story, we sent a reporter and photographer down the Missouri River for three days along with an environmentalist and an official of the Army Corps of Engineers. The two sides often clashed over river and channel management and the preservation of wild lands and natural eco-systems, and we hoped to capture conversations about some of those issues while boating down the Big Muddy. One of my principal roles on this journey was to transport the river travelers by van in between stretches on the river. All of us camped on a mid-river sandbar one night, and I recall waking early and watching the enveloping morning fog slowly dissipate.

In recent decades, while still working in daily journalism, I’ve referred to my extra-curricular activities in Hemingway studies as my own private graduate school. My self-directed program suits me just fine. If I suffer the consequences of not having the proper credentials or training in the research and writing I do, then so be it. I’ve raised the private grad school bar even higher following my newspaper career by completing two literary biographies and recklessly rolling into a third. And, as a longtime book critic and a lifelong reader, I continue to spend each and every day among books and at a keyboard.

I know that’s a long ramble toward mentioning my delight as I was reading John McPhee’s new book, Tabula Rasa. It’s a memoir of sorts and a book about writing and not writing. It offers a collection of brief, miscellaneous pieces reflecting dives into McPhee’s old files to recount how and why a particular story idea didn’t pan out. Or did. Deep into the short book, he writes about the origins of Oranges. He’d noticed an orange-squeezing machine at Penn Station, and one question led to another. Then he dropped into the office of William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, where McPhee at the time was still pitching ideas on contract while teaching and hoping to become a staff writer. One idea or another failed to spark Shawn’s interest. Sometimes, McPhee realized, Shawn might have been protecting the turf of another New Yorker scribe. Then McPhee offered one word. “Oranges.” And he got Shawn’s classic green light: “Yes. Oh, my, yes.”

McPhee’s Tabula Rasa is engaging, charming at times, surprising, humorous, typically masterful and typically dense with detail—the annals of Princeton, New Jersey, for example—that might not appeal to every reader. Still, he manages to turn some of the raw driftwood into intriguing sculpture. He recalls, for instance, how he once thought about exploring one or more of the dozens of towns named Princeton across the nation. Ultimately he dropped the idea as the equivalent of the uninspired journalism practice of anniversary stories, or “of wilderness camping by Jeep Cherokee, of psychoanalyzing the Mummers Parade.”

We learn about the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the monkish pharmalinguists at drug companies who invent unintelligible names for generics, a Hemingway aficionado who happened to be a mediocre journalist he once spied around the bull run at Pamplona, and how certain travels and failed projects may have influenced McPhee’s two younger daughters, both of whom became writers.

The book made me want to go back to some early McPhee pieces—especially one about Kentucky bourbon—that eluded my attention or a place on my book shelves. And it reminded me to marvel again at the depth of McPhee’s reportorial memory and achievements in science and history; at the curiosity that takes readers into the lives of interesting people we might not otherwise meet; and at his ebullient mastery of language and the craft of story.

Recent Readings: Fiction, Biography and Bob

I had the pleasure of appearing again on Steve Kraske’s “Up-to-Date” radio show on KCUR-FM to add my recommendations for fall reading and holiday book buying. The time was tight, so I only got a chance to talk about three books—A.M. Homes’ new novel and biographies by Stacy Schiff and David Maraniss; a blurb about the fourth recommendation, Bob Dylan’s Philosophy of Modern Song, appears on the show’s website:

Here’s the text, published on the KCUR site:

The Unfolding, by A.M. Homes (Viking). Fiction: This serio-comic novel rather sleekly and smartly encapsulates our recent years of political anxiety and divisions. The setting extends from election day 2008 to the presidential inauguration of Barack Obama two and a half months later. Its principal characters include 18-year-old Meghan Hitchens, her politically connected and archly conservative father, known as the Big Guy, and her mother Charlotte. Even as the family confronts its own secrets and disintegration, the weight of history and conflicting notions of the “American dream” propel the reader through a closely observed scenario blending a young woman’s personal awakenings and the makings of political truths and power. A.M. Homes has a sharp eye, a wicked wit, and a highly tuned ear, resulting in a fast-paced novel rich with cultural, emotional, and political insights.

The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams, by Stacy Schiff (Little, Brown). Biography. One of our finest biographers takes us to the American Revolution through the complicated life of a Boston rabble-rouser. Political activist, opinion leader, instigator of the colonial Congress, and sly architect of the march toward independence from the British “mother country,” Adams was fearless, driven, and ultimately controversial. Schiff brings a savvy and scintillating sense of story to the proceedings, making for a crisp read. Her book illustrates how the founding turmoil and lessons of distant American history resonate even today.

Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe, by David Maraniss (Simon & Schuster). Biography. He was the world’s greatest athlete. Football player. Track star. Olympic gold medalist (with an asterisk). Even a pro baseball player, though of uneven skills. But all of that was complicated—disturbingly and tragically—by Jim Thorpe’s identity as an “Indian,” a Native American with roots in the Sac and Fox tribe of Oklahoma. The story of Jim Thorpe, as Maraniss’s clear-eyed and supremely detailed biography reveals, is a story of persistence, survival, love, loss, and the juggernaut of sports, but also a story of how myths are made and how white America manipulated people and denied dignity and honor to “first Americans.”

The Philosophy of Modern Song, by Bob Dylan (Simon & Schuster). Non-fiction/essays. Bob Dylan, the Nobel Prize laureate, is still recording new music and touring in his 80s. Now he has gathered a series of essays on music and culture into an odd yet revealing, occasionally controversial, and ultimately entertaining book. Reflecting the kind of eager and engaging riffing he brought to his “Theme Time Radio Hour” series, Dylan writes about 66 distinct songs representing American pop culture from his youth and middle years. From stars like Little Richard, Ricky Nelson and Frank Sinatra to relative unknowns such as John Trudell, a Native American songwriter and activist. As it becomes clear, these are not necessarily a playlist of his favorite songs, but entry points into the stream of history. Dylan meditates on justice, fame, race, and other topics and presents the kind of intellectual pinballing we’ve come to expect from this pop-culture survivor wholly deserving of his status as sage, poet, and court jester.

From the Archives: A Mamet Discovery Prompts Unearthing This Piece About Hemingway and TV Writing

While researching another project recently at the Harry Ransom Center, on the campus of the University of Texas in Austin, I followed a digression into Hemingway territory and learned something I’d never encountered before. The playwright David Mamet (right) had once set out to write a screenplay based on Across the River and Into the Trees, one of Hemingway’s most problematic novels. Problematic because most critics hold it up as one of Hemingway’s worst. That may or may not be true, but despite its flaws, the book, like several of Hemingway’s lesser works, does serve up some elegant writing here and there. So, Across the River, published in 1950, is at least approachable on a prose, or sentence-by-sentence, level.

Mamet recognized the novel’s reputation but once noted in an interview that great plays often lead to lousy movies and perhaps the reverse may have been true for a bad book. I’m not sure his logic on paper was quite that clear, but I think that was what he was trying to say.

Mamet has often been creatively compared to Hemingway, which, in that same interview (with Playboy, in 1995) he deflected: It would be a “heavy, impossible burden. You know, you can’t play Stanley Kowalski without being compared to Marlon Brando – even by people who never saw Marlon Brando in the movie, let alone on stage. He revolutionized that role and the American notion of what it meant to act. The same is true of Hemingway and writing.”

That said, the discovery of these Mamet notes sent me back to a newspaper piece I wrote – yikes, sixteen years ago -- that connected some dots between Mamet and Hemingway through the craft of television writing. That piece also made a nod to the likes of Aaron Sorkin and Amy Sherman-Palladino, the creator of a TV series of the day called “Gilmore Girls” and now the creative spirit behind one of the most popular and lauded new streaming series, “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” (on Amazon Prime). Again, Hemingway. I watched a few more episodes of “Mrs. Maisel” the other day, which gave me further impetus to repost this piece.

The following article first appeared in The Kansas City Star in November 2002.

Motor mouths: Smart and savvy TV writers figure it out: Papa knew best

“Wall Street Journal says people are talking really fast on

television.”

“You don't say.”

“No, really. Especially on `West Wing.' “

“Smart show.”

“That's right. Mostly written by a guy named Aaron Sorkin.”

“All that politics _”

“Ripped from the headlines!”

“And real-life drama.”

“It's nice that Bartlet and his wife are getting closer.”

“Illness will do that.”

“I suppose. But it's about -- “

“Power and powerlessness.”

”Good way to put it, but I've been thinking about this TV thing for a

long time. And one thing the Journal didn't mention -- “

“Only one?”

“Well, a few things, but one important one was the real source of that

dialogue.”

“Yeah?”

“Straight out of Hemingway.”

“Howzat?”

“Sun.”

“Sun?

“The Sun Also Rises. All that Paris banter. All those young hipsters.”

“All that drinking -- “

“That, too, but I first noticed this a few years ago on another show

Sorkin did -- `Sports Night.' “

“That ESPN thing.”

“Something like that. But it was great. Behind the scenes at a sports

talk show that had virtually nothing to do with --”

“Sports.”

“Yeah. It was all about the people. And they talked fast, and they

talked on top of each other and they completed one another's --”

“Sentences.”

“You've got it. And for some reason that's why I put two and two

together.”

“And came up with Hemingway.”

“Listen to this. It's when Jake Barnes invites a passing woman to sit

down and have a drink. He's the narrator:

“What's the matter?” she asked. “Going on a party?”

“Sure. Aren't you?”

“I don't know. You never know in this town.”

“Don't you like Paris?”

“No.”

“Why don't you go somewhere else?”

“Isn't anywhere else.”

“You're happy, all right.”

“Happy, hell!”

“I see what you're talking about.”

“Things happen fast on TV comedies, and even some dramas, and this

article I read said it had to do with cramming lots of scenes in a show to

keep people laughing. Wears some people out. ‘Lucy’ was funny. But

‘Seinfeld’ was faster. Just like those old screwball comedies from way back

when.”

“Yeh, yeh, yeh.”

“I might add that ‘Frasier’ is just as clever, more urbane, but

slower.”

“It takes time to make a latte.”

“And you know `Seinfeld,' that show about nothing.”

“Yada yada yada.”

“Exactly. Know where that comes from?”

“I'm getting a feeling --”

“Yep. ‘A Clean Well-Lighted Place.’ Seinfeld did yada yada. Hemingway

did nada nada. Read it and weep.”

“Will do.”

“These really good TV guys -- Sorkin, David Chase --”

“ ‘Sopranos.’ “

“Yup. And Matt Groening _”

“ ‘Simpsons.’ “

“Roger.”

“Homer?"

“No. Roger. As in `Roger that.' You're right. ‘Simpsons.’ But what I was

trying to say -- “

“Before I interrupted --"

“Was that the best of this stuff seems to be so aware of things. Aware

of the world. Aware of pop culture.”

”Uh huh.”

“I mean, some of these guys even love books.”

“I'll never forget that Jack London episode of ‘Northern Exposure.’ “

“Brilliant. That's what I mean. Or Amy Sherman-Palladino.”

“Who?”

“She writes `Gilmore Girls.' There's some media-savvy dialogue, for you,

even though it feels a little forced.”

“She's no Hemingway, you mean.”

”Well, I don't think I'm too far out on a literary limb with that

theory. Surely Sorkin read `Hills Like White Elephants.' “

“Who hasn't?”

“One thing you hear a lot is wordplay. Repetition. You accent something

by repeating it two or three or more times.”

“Repetition.”

“It's like ping-pong words. Not sing-song to put you to sleep. Ping-pong to

keep you alert.”

“Back and forth you mean?”

“Words ping-ponging, or pinballing. Like one time on `Gilmore Girls'

Rory and a friend were riffing on the word ‘wing-it.’ They didn't know they

were riffing, they were just saying what the writers wrote. But ‘wing-it’ as

a compound verb and an adjective, meaning just the opposite of ‘Zagat,’

meaning you'd look it up in the restaurant guide rather than wing-it. The

friend was having a date and she was worried about not looking

at Zagat and they'd be forced to wing-it. Zagat. Wing-it.”

“Wow.”

“It's like action poetry.”

“Poetry? On television?”

“TV is literature, you know. I mean look at ‘Sports Night.’ “

“It's a shame they killed it.”

“Yeah, that really torqued my chili.”

“Peter Krause was great.

“Just like he is on `Six Feet Under.' And now one of those `Sports

Night' guys is on ‘West Wing.’ “

“The guy with glasses.”

“But Felicity What's-Her-Name -- she played the lead character, the

talk-show producer -- was married to William H. Macy and they were great,

too.”

“Great character -- Macy. The ratings consultant.”

“Huffman. Felicity Huffman. And they're theater people.”

“Really?”

“They do Mamet. I mean they're friends with Mamet.”

“Mamet?”

“The F-word guy. Plays. Movies.”

“Yeah, I know, I know. But did you just say, ‘It really torqued my

chili’?”

“Did.”

“Where'd that come from?”

”People talk that way.”

“C'mon --”

“No, they do. The beauty of language. I love it. ‘Torqued my chili.’

Some guy from Oklahoma says it. I heard it at a diner.”

“A diner?”

“You know, like in `The Killers.' “

“Ernie again?”

“Short story.”

“Kind of like television.”

“Except without the ads.”

“Another reason they talk fast, right?”

“Yeah. To squeeze in more -- “

“Commercials."

On the PEN/Hemingway beat: An Interview With Weike Wang

I wrote this account of the 2018 PEN/Hemingway Award event for the newsletter of the International Hemingway Society. Here it is, including a brief interview with Weike Wing, author of the award-winning novel, Chemistry.

By STEVE PAUL

This was a transitional year for the annual PEN/Hemingway literary awards, which the Ernest Hemingway Foundation has co-sponsored for more than four decades. Not long before the April 8 awards event in Boston, our longtime co-sponsor, the New England PEN organization, ceded administration of the program to its parent organization, PEN America. The New York-based advocacy group oversees a long lineup of annual literary awards.

Without the presence of New England PEN and its own regional literary awards, this year’s event at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum was somewhat smaller than usual but wholly focused on the Hemingway award, which honors a first book of fiction. Seán Hemingway (pictured above with Weike Wang), standing in for his uncle Patrick, oversaw the proceedings, in which the 43rd annual PEN/Hemingway award went to Weike Wang, author of the novel Chemistry. (More on Wang and her book below.)

The audience heard from awards judge Geraldine Brooks and Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America, which is operating in overdrive, she said, during a “crisis for expression in our own country.” Ricardo Cortez Cruz, author of the novel Straight Outta Compton and professor of English and creative writing at Illinois State University, gave a stirring keynote about Hemingway and “the joy and optimism that comes with knowing that writing can change the world.”

Dr. Hilary K. Justice (pictured at the lectern), specialist at the JFK’s Hemingway Collection, opened the proceedings with a smart and lyrical essay based in part on her call for the Hemingway community to identify their favorite Papa sentences.

The PEN/Hemingway program also highlighted two finalists: Lisa Ko, for The Leavers, and Adelia Saunders, author of Indelible. Honorable mentions went to Ian Bassingthwaite for Live from Cairo, and Curtis Dawkins, author of the prison novel The Graybar Hotel.

Wang receives $25,000 and residencies at the University of Idaho and the Ucross Foundation in Wyoming. The runners-up receive smaller amounts. Along with our Ernest Hemingway Foundation and PEN America, sponsors of the program include the Hemingway family, the JFK Presidential Library and Museum and its associated support organizations.

Weike Wang’s Chemistry is a briskly moving short novel about a young woman, daughter of Chinese immigrants, who is struggling with her American identity, her family and boyfriend relationships, and with the doctoral chemistry lab that threatens to define her future. A few days after the ceremony in Boston, I got in touch to command her attention for a brief email interview. It appears here with only slight revisions for clarity.

Q. First, can you give me a recap of your path towards writing? You apparently were in another field (chemistry? public health?), so when, how, and why did you veer into fiction?

A. I was undergrad chem and English. I was also premed. Then the latter didn't quite work out and I moved into grad school for cancer epidemiology. I have always been writing fiction, but I don't think it is necessarily a profession you go into as it is one you fall into. When I finished the MFA and wrote this novel, I had no idea any of this would happen. I had hoped, but never actually thought it would. I can sometimes be self destructively practical. Had the novel not worked out, my plan was then to find a job in epi and move on from writing.

Q. There are no right answers here, but in your workshopping and MFA did you develop any ideas or relationship, pro or con, with Hemingway? It's always interesting, because very few PEN/Hemingway winners -- the books, I mean -- feel as if they've been influenced by his work.

A. That is true, but I did read the story “Hills Like White Elephants” during my MFA. I came to Hemingway's work fairly late, in college and later I would say. But I have a good relationship with Hemingway's work. I learned a great deal from him in terms of dialogue (especially from the above story) and shaping a piece of fiction to mimic something in real life yet to still be inherently fiction. What I love about that first story I read of his is the explosiveness both explicit and subversive.

Q. Your reading on Sunday really heightened the humor that seasons your novel. I've been thinking about that and wonder whether humor is a concerted strategy or comes out of your natural authorial voice or emerges from your vision of the narrator's character?

A. Voice, I believe. I don't think I could write anything without some ounce of humor. You cannot have dark without light. Humor has been my natural way of coping with growing up. But I do think it works well in writing and I take a leaf of that ability from teachers like Amy Hempel and Sigrid Nunez.

Q. Sorry for the obvious question, but does your narrator's experience reflect elements of your own life or is she wholly invented? This, of course, is a Hemingway issue, given that readers always seem to expect that he was writing about his own life.

A. Ah. When I met Seán at the lunch, he told me he had read some earlier drafts of “Hills Like White Elephants” and the very first draft read more like a recorded conversation and was probably a recorded conversation between Hemingway and Hadley. Then the shaping of the work happened and now we have this brilliant story that has no bearing with the original conversation but used it as a springboard. That is how I feel about this book. I took a lot of elements from my life. The science and PhD world is as part of me as football and baseball lingo is to my husband. The longer I write the more I see that transforming the prose is a large part of being the writer. Much of that transformation happens in revision, hence why revision is so paramount.

Q. The structure of "Chemistry" seems something like an orchestration of atomic particles and really benefits from its non-linear but ultimately forward motion. How did you determine to write the novel that way?

A. I think the non-linear narration came from my inability to write a straight story from event to event. I favor the collage structure. I think it gives the reader and writer a more immersive experience. I also found something clunky about going from chapter to chapter, putting in a “cliff hanger,” finding the “hook.” Much of the book is also about language and the flow of language, so I wanted it to move fairly seamlessly.

A. What's next for you? Also, are you still teaching?

Q. More books! Hopefully. I am working on a second novel and stories. I'm not teaching this semester but I will be next semester at Barnard and UPenn. Teaching is pretty fun. Students are funny, in a good way. But also I guess in a funny way.

Hemingway Society member Steve Paul is author of Hemingway at Eighteen: The Pivotal Year That Launched an American Legend (Chicago Review Press, 2017).