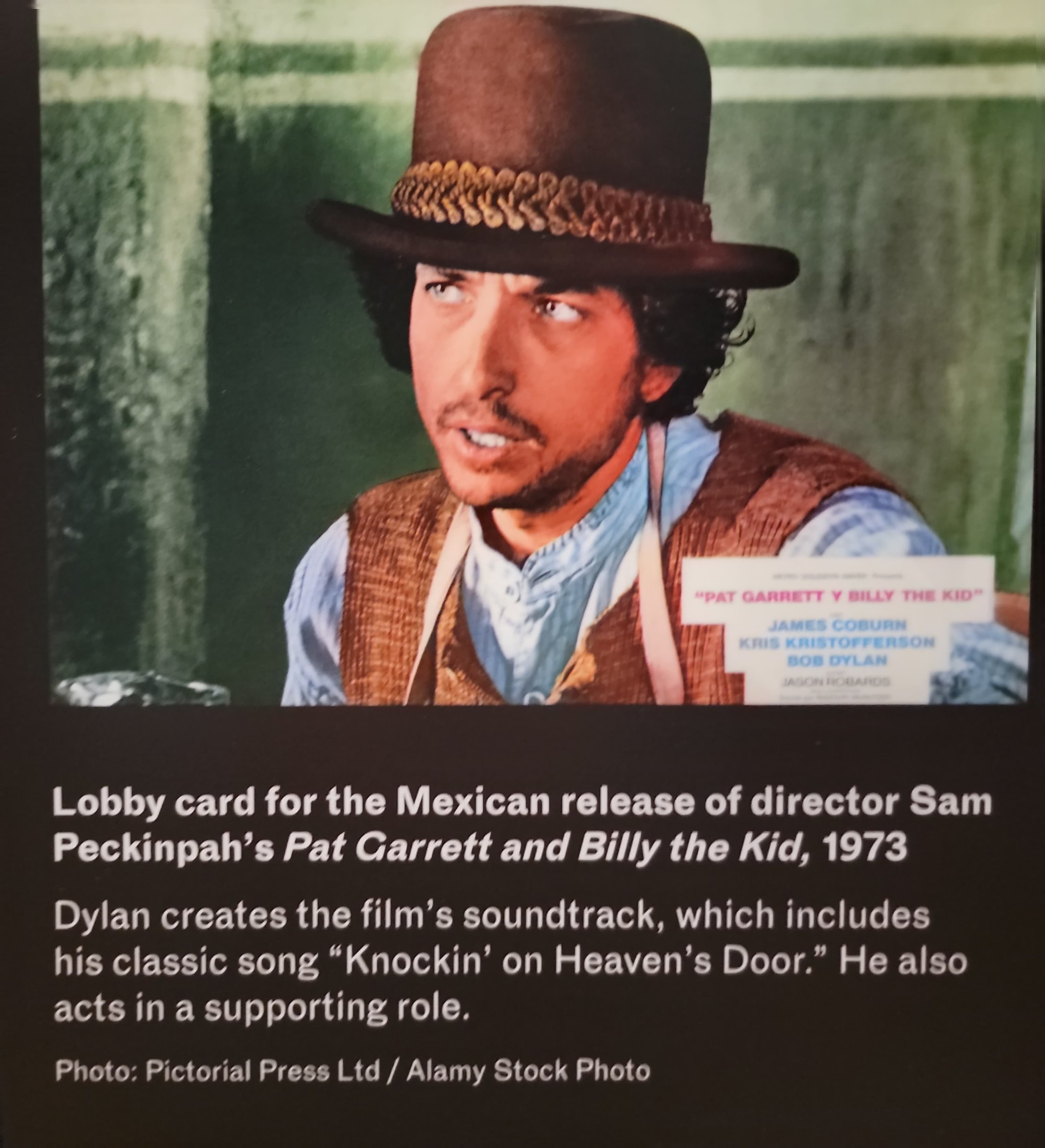

Before he could make his own movies, however, he had to stick around for the completion of this one.

Production logs indicate there were other days when Dylan was missing in action or didn’t arrive at a rehearsal. On Feb. 5 he was reported lost while trying to find the shooting location. Dylan conceded that by that point he was just going through the motions. “Why did I do it, I guess I had a fondness for Billy the Kid. In no way can I say I did it for the money. Anyway, I was too beat to take it personal. I mean, it didn’t hurt but I was sleep walking most of the time and had no real reason to be there.”

The shooting wrapped a few days later, and the proceedings moved to Los Angeles. Dylan and family took up residence in a rented house in Malibu.

Two recording sessions took place that month at Burbank Studios. Dylan recorded instrumental and vocal versions of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” He apparently got word that Peckinpah preferred the song without the singing. “All right, let’s do it without a vocal…[but] this is the last time I work for anyone in a movie on the music. I’ll stick to acting.”

At the second Burbank session Dylan was joined by Roger McGuinn, drummer Jim Keltner, and Bruce Langhorne, the guitarist who had made that shimmering instrumental soundtrack for Peter Fonda’s “The Hired Hand.” The musicians played as rushes from pertinent scenes were projected above them. Watching the death of Sheriff Baker while playing “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” made a visceral connection. Said Keltner, “I cried through that whole take.”

Under pressure from the overlords at MGM Studios, Peckinpah had less than three months to turn his daily rushes into a feature film. They wanted it released around Memorial Day, 1973. Well into the editing process, Peckinpah notoriously balked and walked out. No one was really happy with the final cut—there were two preliminary “preview” versions, and one of them was released anyway.

Dylan eventually expressed his frustration over the finished film’s soundtrack to Cameron Crowe. “The music,” he said, “seemed to be scattered and used in every other place but the scenes in which we did it for. Except for ‘Heaven’s Door,’ I can’t say as though I recognized anything I’d done for being in the place that I’d done it for.”

Despite the somewhat shoddy release, which omitted a handful of key scenes, and despite Dylan’s unhappiness with how his music was treated, or mistreated, he recognized Peckinpah’s achievement. In an unpublished notepad jotting, Dylan complained about critics who panned it, but, as found in an unpublished fragment in his archive, he called the final product “THEE Billy the Kid movie.”

A year after the film’s opening, a newly installed MGM official tried to lure Peckinpah back to consider re-editing the movie. Peckinpah declined, but among his observations were that something had to be done about the score. Dylan’s music seemed thin, he told Daniel Melnick.

The film underwent a long and colorful history. Turner Movies released a purported “director’s cut” in 1988, which, as it happened, replaced the vocal version of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” with an instrumental take. Eventually, Paul Seydor was commissioned to re-edit the movie and in 2005 finally transformed it into a “special edition,” something that, he argued, more closely matched Peckinpah’s intentions. It’s terrific.

“It is a cliché of Western fiction and film,” Seydor writes in his 2015 book, “that the way of life of the Western hero, be he cowhand, sheriff, or outlaw, is being pushed aside by forces of progress that are increasingly fencing in or crowding the last open spaces.” Often underlying that theme is a darker one—“how the Western way of life itself, transitory by its very nature, contained the seeds of its own destruction, its people, hero and villain, complicit in its (and their own) destruction. I’ve rarely seen this complex of themes better realized than in Wurlitzer’s screenplay and the deeper, rich film Peckinpah eventually made from it.”

Peckinpah was long gone when the 2005 DVD re-release occurred. He had died in 1984. By then Dylan made a stab at condensing his Peckinpah movie experience into the Mexican-inflected “Romance in Durango” and punctuated every Rolling Thunder concert with “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” tacking on at least one new verse that carried an anti-war sentiment. And he had gotten past his Hollywood resistance by making a movie reflecting his own vision and his own rules—the Rolling Thunder offshoot “Renaldo and Clara.”

One could consider those projects as part of the ongoing laboratory of Dylan’s experimental personas. Witness Dylan as Jack Fate in “Masked and Anonymous” (2003), directed by Larry Charles. And then, in 2007, came “I’m Not There,” Todd Haynes’s movie exploring the many distinct innards of Dylan. It’s all of a piece—the never-ending dissection of a mysterious, incomplete, and ever self-inventing man called Alias.

Works Cited/Consulted

Aghed, Jan. “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” Sight and Sound 42 (Spring 1973), reprinted in Hayes, Sam Peckinpah Interviews, 121-136.

Burns, Sean. “‘Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid’: Peckinpah's Unfinished Masterpiece.” WBUR, Aug. 10, 2015. https://www.wbur.org/news/2015/08/10/pat-garrett-billy-the-kid

Crowe, Cameron. Biograph liner notes booklet, Columbia Records, 1985.

Dettmar, Kevin J.H., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009.

Dixon, Jonathan. “Writer Rudy Wurlitzer’s Underappreciated Masterpieces,” Vice, Feb. 25, 2015. https://www.vice.com/en/article/wd43ab/the-inteior-frontier-0000581-v22n2

Dylan, Bob. The Philosophy of Modern Song. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Bob Dylan Papers, the Bob Dylan Archive, Tulsa.

Epstein, Daniel Mark. The Ballad of Bob Dylan: A Portrait. New York: Harper, 2011.

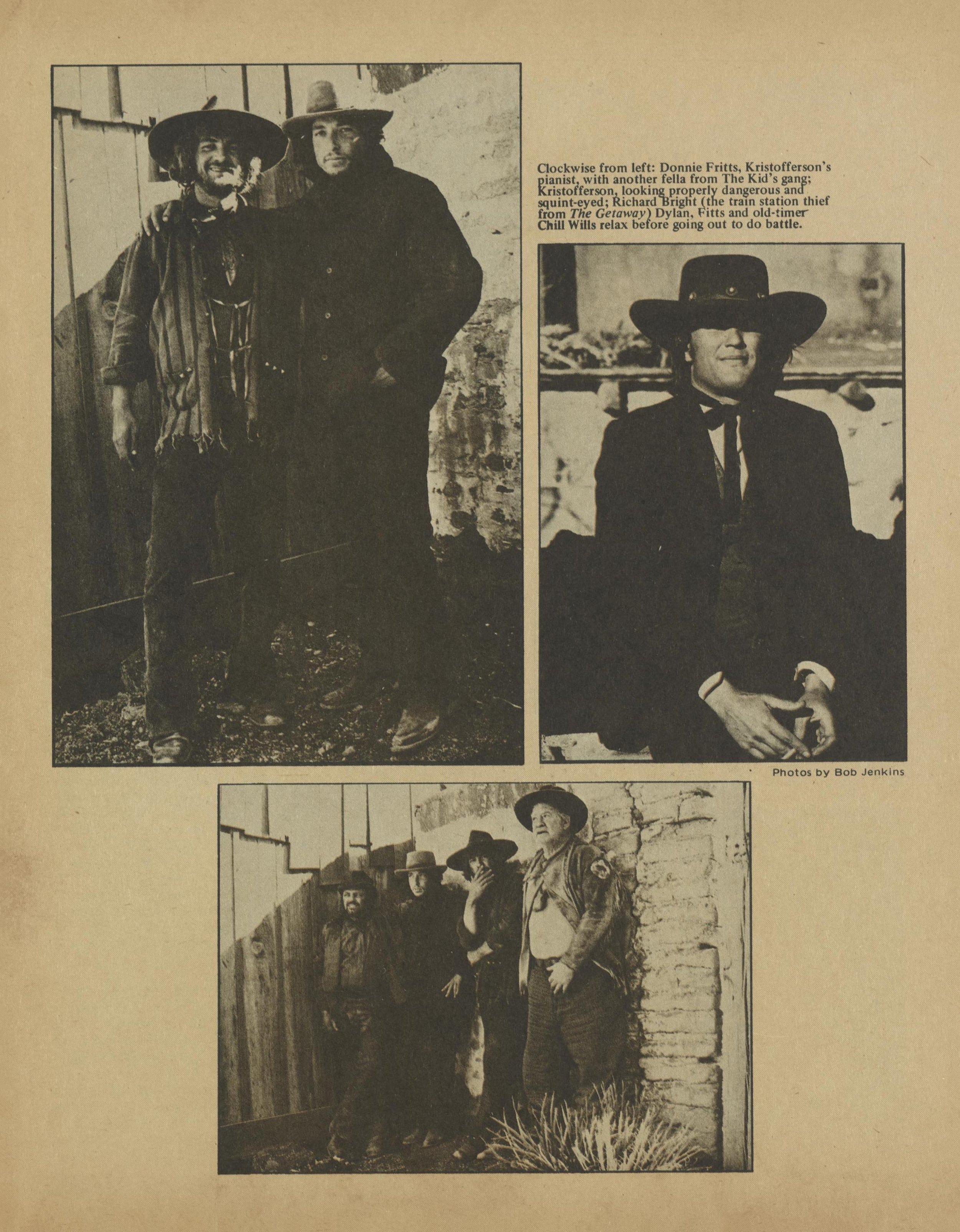

Flippo, Chet. “Dylan Meets the Durango Kid: Kristofferson and Dylan in Mexico,” Rolling Stone, March 15, 1973. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/dylan-meets-the-durango-kid-kristofferson-and-dylan-in-mexico-242768/

Hayes, Kevin J., ed. Sam Peckinpah Interviews. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2008.

Herren, Graley. “Dylan’s Holy Outlaws,” https://shadowchasing.substack.com/p/dylans-holy-outlaws

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. New York: William Morrow, 2001

----------. Bob Dylan: A Life in Stolen Moments, Day by Day: 1941-1995. New York: Schirmer Books, 1996.

----------. Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions, 1960-1994, New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1996.

----------. Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Vol. 1: 1957-73. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2009.

“The Hired Hand.” Peter Fonda, director.

Hoberman, J. The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. New York: The New Press, 2003.

Jacobs, Rodger. “Rudy Wurlitzer, Bob Dylan, Bloody Sam, and the Jornado del Muerto,” Popmatters, July 30, 2009. https://www.popmatters.com/109095-the-last-of-the-real-outlaws-2496063564.html

Licht, Alan. “An Interview with Rudy Wurlitzer.” The Believer 98, May 1, 2013. https://www.thebeliever.net/an-interview-with-rudy-wurlitzer/ Also found on openculture.org.

Margotin, Phillippe and Jean-Michel Guesdon. Bob Dylan: All the Songs, The Story Behind Every Track. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2021.

Marsh, Dave. “Duel to the Death: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” Creem, July 1, 1973. https://archive.creem.com/article/1973/7/1/duel-to-the-death-pat-garrett-and-billy-the-kid

“McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” directed by Robert Altman, 1971.

McClure, Michael. The Beard. New York: Grove Press, 1965.

----------. “Bob Dylan: The Poet’s Poet,” Rolling Stone 156, March 14, 1974; reprinted in McClure: Lighting the Corners: On Art, Nature, and the Visionary, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico College of Arts and Sciences, 1993.

Padgett, Ray. Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, Burlington, Vermont: EWP Press, 2023.

Sam Peckinpah Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, “Pat Garrett and Billy” production log, folder 786, and music notes, folder 788. Other documents from the Turner MGM collection, P277.

Peckinpah, Sam, as director: “Ride the High Country,” “The Wild Bunch.”

Prince, Stephen. Savage Cinema: Sam Peckinpah and the Rise of Ultraviolent Movies. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998.

Rogovoy, Seth. Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet. New York: Scribner, 2009.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. “The Countercultural Histories of Rudy Wurlitzer.” Written By 3, no. 11, November 1998. Online: The Countercultural Histories of Rudy Wurlitzer | Jonathan Rosenbaum

Scaduto, Anthony. Bob Dylan: An Intimate Biography. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1971.

Seydor, Paul. The Authentic Death and Contentious Afterlife of “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid”: The Untold Story of Peckinpah's Last Western Film. Evanston: Northwestern UP, 2015.

-----------. “The Music of Sam Peckinpah’s Films,” The Absolute Sound, March 10, 2015.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. New York: Morrow/Beech Tree, 1986.

Shepard, Sam. Rolling Thunder Logbook. New York: Viking Press, 1977; reprinted by Limelight Editions, 1987.

Taylor, Jack, dir. “The Return of ‘The Hired Hand,’” documentary film, 2003.

“Two-Lane Blacktop,” directed by Monte Hellman, 1971.