STEVE PAUL

(c) 2024

While listening to Billie Holiday’s celebrated record “Lady in Satin,” from 1958, I was struck by repeated aural reverberations that wanted to connect with Bob Dylan. Here was, like Dylan, a singer with a distinctive, idiosyncratic voice making singular, artistic expressions with the lyrics of a dozen or so standards from jazz and popular music of the day. In Holiday’s case, the songs happened to be arranged with sophisticated orchestral accompaniment, including strings, which is mixed respectfully underneath her vocal sounds.

Holiday’s voice could indeed be divisive, as Dylan’s has always been. In 1958, some 25 years into her singing career and a year away from her death, Holiday was struggling with drink, drugs, and disturbingly violent marital conflict. Yet she made it through three late-night recording sessions, often haltingly, and produced these songs of heartache that become instantly mesmerizing. “I’m a Fool to Want You.” “Glad to Be Unhappy.” “You Don’t Know What Love Is.” “I’ll Be Around.” Awesome.

Count Basie, who employed Holiday in his band for nearly a year in the late 1930s, once noted that she “had a really strange way of delivering a song.” Yet, he added, “All so wonderful.”

Think of how many times we hear admiration for the ways Bob Dylan phrases, rephrases, and experiments with the phrasing of even his own classic songs. And think of the way that in recent years Dylan has turned back to American standards in recordings and concerts.

In the recent “Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour,” the setlist often included such songs as “Melancholy Mood” and “That Old Black Magic,” both of which he covered on the “Fallen Angels” record of 2016 and both of course indelibly identified with Frank Sinatra. Dylan’s three-package string of standards recordings, also including “Shadows in the Night” (2015) and “Triplicate” (2017) amounted to a collective tribute to Sinatra, whose crooning heights he seemed to want to emulate.

Dylan didn’t have much to say about Sinatra in his recent book, The Philosophy of Modern Song. This collection of essays and improvisations provided him with an outlet to mull over 66 records that presumably informed his ears, especially in the early decades of his musical life. For some reason Sinatra hated his melancholy pop hit “Strangers in the Night” (1966; I remember it all too well), then, without getting at why, Dylan goes on to explore the contentious provenance of the song. Dylan only mentions Billie Holiday in passing, while musing on Judy Garland’s version of “Come Rain or Come Shine.” (This is where the relentless researcher complains that Dylan’s book really should’ve included an index.)

Dylan, in his book, is short on the specifics of the craft that he admired or learned from in his musical education. He is long on feelings and emotional connections, on the imagery songs fire up in listeners’ brains. And he is eminently quotable. Art is not to be understood, only “appreciated or interpreted,” he writes. “Whether it’s Dogs Playing Poker or Mona Lisa’s smile, you gain nothing from understanding it” (298-9).

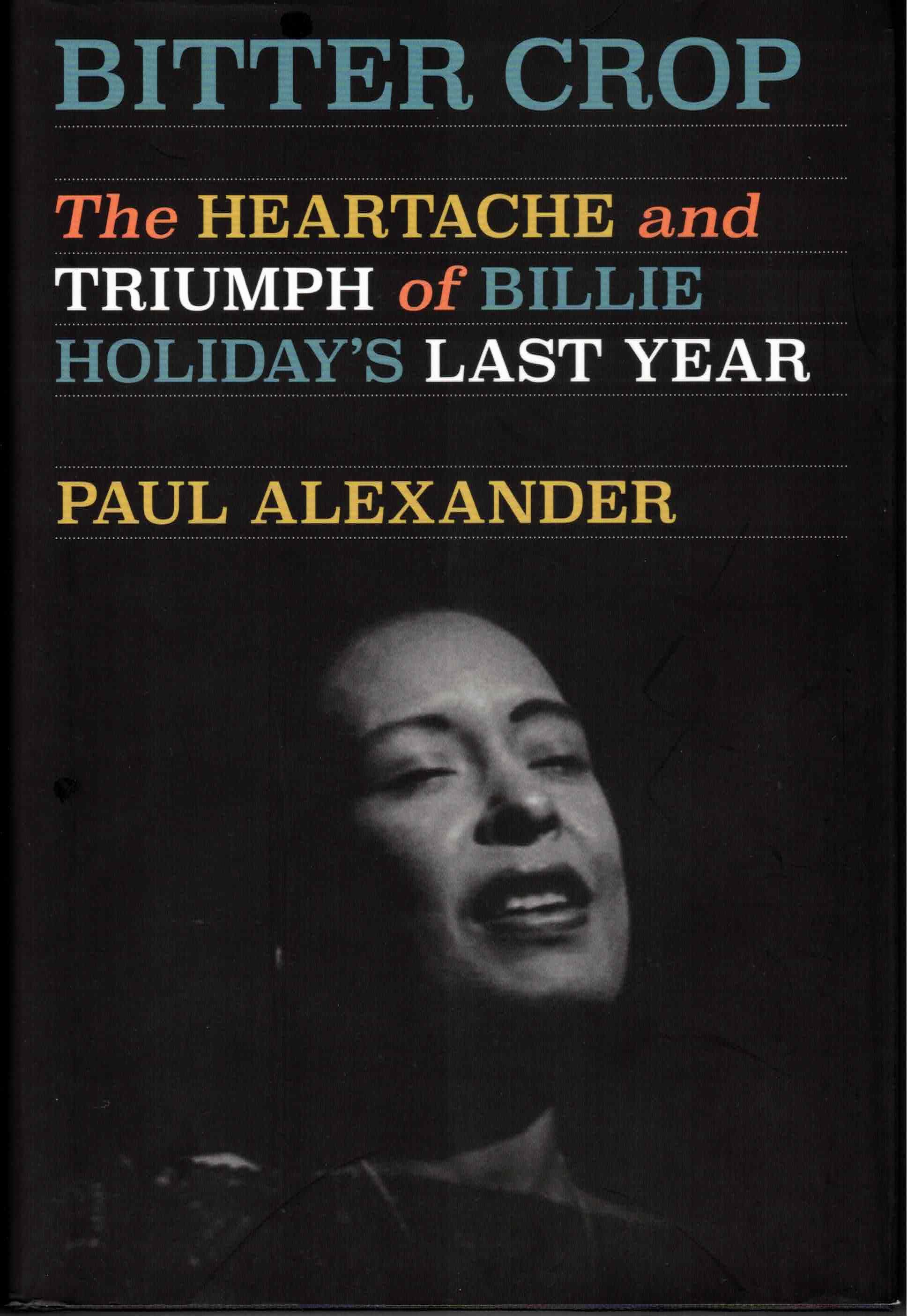

I was prompted to go back to “Lady in Satin” while reading a recent biography, Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday’s Last Year, by Paul Alexander.

As Alexander dutifully reports, based on Holiday’s often fanciful memoir, Lady Sings the Blues, and interviews of the day, Holiday contends she taught Sinatra how to “bend a note”—as Alexander puts it, “to enhance his phrasing, qhat became the hallmark in his singing style” (56). So far as I know, there’s no reason to doubt this. Indeed, if it’s true, then the line from American songbook to Dylan ought to extend right through his hero, Sinatra, to the previously unacknowledged Billie Holiday.

Consider this an introductory. I have more listening to do in order to go more deeply into this possibly wishful-thinking idea.