Christopher Nolan’s new movie, “Oppenheimer,” has sparked a boatload of newsy and literary chatter. As I was reading one of biographer Kai Bird’s recent essays on his role in the Oppenheimer project, it occurred to me I had a small slice of life connecting Oppenheimer with William Stafford, the subject of my own project, now in its third year of research and writing.

By STEVE PAUL

(c) 2023

When the little-known Oregon writer and teacher William Stafford won the National Book Award in Poetry in 1963, he strangely crossed paths with the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Strange because the so-called “father of the atomic bomb” gave the keynote speech at the award ceremony in New York and Stafford was a committed pacifist, some of whose recent poems reflected his and the nation’s nuclear anxieties of the day.

Given that Oppenheimer’s new cultural moment in the U.S. coincides with my current work in progress, a biography of the Kansas-born Stafford, a few words about their mutual brush with fame seem timely.

In developing his new film, “Oppenheimer,” the director Christopher Nolan turned to a majestic biography of the scientist published in 2005. The book, American Prometheus, was the product of an enormous amount of research conducted by the historian Martin Sherwin. Some 20 years into it, Sherwin was paired with the writer Kai Bird, who spurred the project toward completion. (Sadly, Sherwin didn’t live to see the film’s completion. He died in October 2021.)

The New York Times recently told the story of the long-in-the-making project, and Bird himself wrote an essay for The New Yorker, which recounted a drawn-out and only recently successful campaign to restore Oppenheimer’s reputation. Nearly 70 years ago, in the midst of the Communist-hunting hysterics stirred by Sen. Joseph McCarthy, a tribunal of the Atomic Energy Commission accused Oppenheimer of spying for Russia and stripped him of his security clearance. As Bird writes, Oppenheimer “had to be silenced because he was opposing the development of the hydrogen ‘super’ bomb. Ever since, historians have regarded him as the chief celebrity victim of the national trauma known as McCarthyism.”

Yet it took the passage of nearly a dozen presidential administrations before Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, in December 2022, responding to a persistent consortium of historians and scientists, including Bird, nullified the humiliation of 1954.

Oppenheimer is said to have been publicly diminished by the episode. He “lived out his life a broken man,” the New York Times wrote while reporting on Granholm’s decision and seeming to skim over the fact that that in subsequent years Oppenheimer continued to serve as director of the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton University. He died in 1967.

And yet, there he was, on March 12, 1963, in front of a thousand book people at the National Book Award ceremonies in the swank ballroom grandeur of the Americana Hotel. Sherwin and Bird make no mention of this event in American Prometheus. When I reached out to Bird in October 2021 wondering if the authors’ files might have details, he told me that he had learned just that morning that his co-author had died. I rather awkwardly backed away and let it drop.

Nevertheless, archival documents and media coverage helped fill in some blanks.

Stafford’s Traveling Through the Dark, published by Harper & Row in August 1962, prompted the award judges to conclude, “William Stafford’s poems are clean, direct, and whole. They are both tough and gentle; their music knows also the value of silence.”

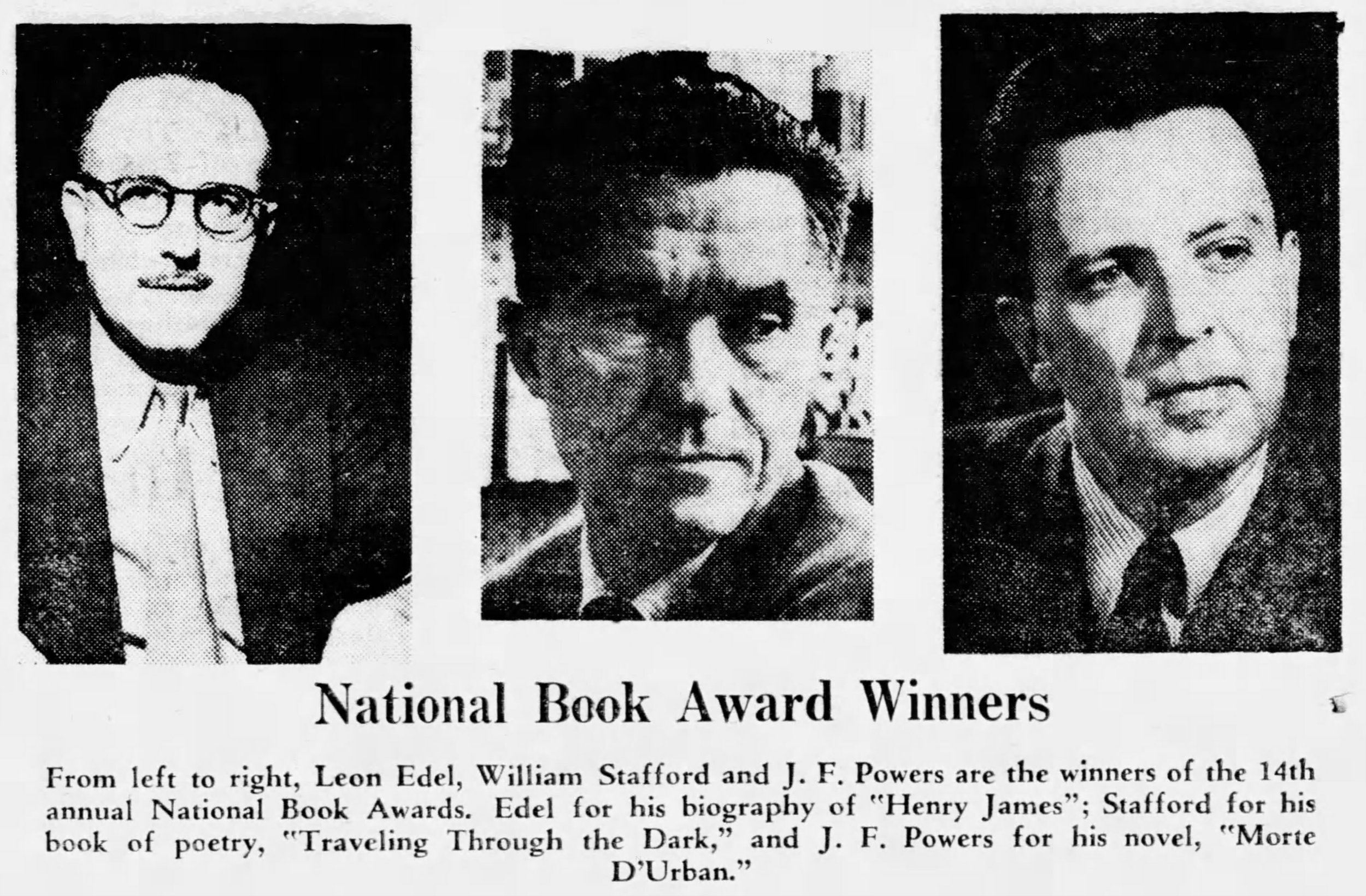

Stafford and the other honorees—the novelist J.F. Powers (Morte D’Urban) and Leon Edel, cited for the first two volumes of his biography of Henry James—received their one thousand dollar checks and made their remarks.

At a news conference that day in New York, Stafford, who was a soft-spoken professor of English at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, recalled his book-hungry family and their frequent treks to the library as he was growing up in the 1920s in Hutchinson, Kansas. And he hinted at a key source of his pacifism: “Though my mother thought the Boy Scouts too militaristic, my brother—the reckless one of the family—joined; and we could all use his official canteen when we picnicked.” When World War II arrived, Stafford’s brother, Bob, joined the Army air corps. Stafford registered as a conscientious objector and spent the war years in a series of Civilian Public Service camps, building roads, fighting forest fires and writing his way into his future life as a poet. And Oppenheimer, of course, led the secret mission at a laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to develop an atomic weapon that could bring a swift end to the war.

As the NBA’s featured speaker, Oppenheimer seemed to blend science and faith under a theme of human responsibility. In speaking about technological progress and mysteries that lay ahead, he also invoked Saint Matthew: “And which of you taking thought can add to his stature by one cubit?”

Oppenheimer concluded with this anecdote, according to a reporter, William D. Snider: “Three weeks ago a high officer of the National Book Committee asked for a title for this talk. I did not have one, but promised to call back shortly, and gave the title that is before you (‘The Added Cubit’). The officer protested that my title was indeed puzzling and uninformative. I said that it had a history and when the officer asked, I quoted St. Matthew. And then the officer asked, ‘From what book is that?’ The National Book Committee still has a lot to do.”

Snider’s article failed to note whether the room erupted in laughter. Stafford, for one, would have appreciated Oppenheimer’s spiritual reference as well as his impish humor in the moment, just like his own.

Stafford and Oppenheimer certainly would have bonded, if only through their bearing as men of conscience and witness. Stafford had written of war’s vast destruction in a poem even before Hiroshima: “There are more cities going into the sky,/ helplessly, than ever before” (“These Mornings,” 1944). One of Stafford’s most enduring poems, first published in 1957, is “At the Bomb Testing Site.” It’s unclear whether Stafford was channeling Trinity, that first atomic bomb test of 1945, or representing the ongoing bomb testing in the desert West in the 1950s, which continued spewing radioactive materials into the atmosphere. Yet, in reading the poem, one can’t help but think of that New Mexico scene in 1945, the mushroom cloud ascending and Oppenheimer thinking of a line from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Stafford’s take is much more subtle and glancing; it closes with a lizard gripping the desert sand. (see the full text below.)

The poet Sir Stephen Spender, interviewed in 1987, recalled how he’d run into Oppenheimer sometime in the 1960s. Oppenheimer pointed to a book he was reading. Poems by Stafford—though we can only imagine it was Traveling Through the Dark, the NBA award winner. Spender regretted he’d never told Stafford the story before. As he put it, Oppenheimer told him Stafford’s work was “the real thing.”