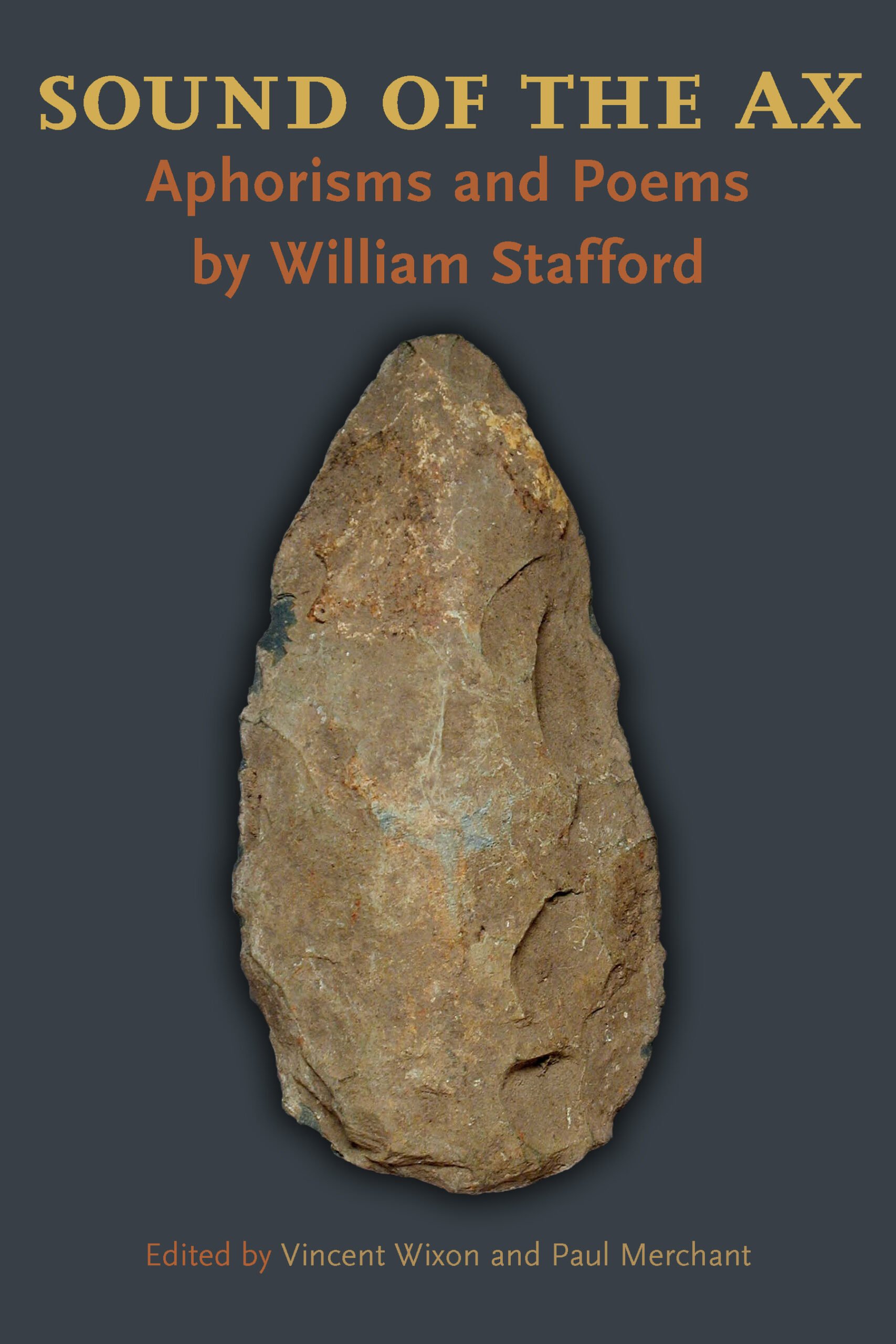

Stafford scholars Vincent Wixon and Paul Merchant celebrated the practice in a valuable collection, Sound of the Ax: Aphorisms and Poems by William Stafford. Published in 2014 by the University of Pittsburgh Press, the book presents more than 400 items and prompted the poet Naomi Shihab Nye to conclude, “These brilliant lines are tuning forks, weather reports from a resonant interior world, to help us with the mysterious days confounding us. Dip in anywhere, repeatedly.”

In my scouring of the Stafford record, I frequently highlight lines that resonate in this way. It occurred to me that, since my biography of Stafford remains a thing in progress, I shouldn’t have to wait to share more of his compressed thoughts.

It’s likely that some of my finds also appear in Sound of the Ax, but most of them are new, I think, and I expect the collection posted here will grow as I revisit various Stafford books and continue to page through the poet’s archives of writings and correspondence. Stafford turned his attention to the whole world, but the process of writing becomes a naturally recurring topic. Some lines collected here are less aphoristic but leapt forward as glimmering poetic gestures worthy of heightened attention.

Items are generally identified by their sources; often the poems are listed by their first book appearance, though many of Stafford’s most memorable poems are also collected in the posthumous The Way It Is. Unless otherwise noted, most drafts and unpublished material come from the William Stafford Archives in the Watzek Library at Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon.

—Steve Paul

“Writing is a reckless encounter with whatever comes along.”

— “Making a Poem/Starting a Car on Ice,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“My debt to the world begins again,/ that I am part of this permanent dream.”

— “Glimpses,” A Glass Face in the Rain

“We are surrounded, not by emblems, by paragons or villains, or fragments from Heaven and Hell, but by ready and adjustable potentials: nothing is special, everything is maybe.”

— “The Importance of the Trivial,” prose draft, c. September 1964

“Anyone in the breathing business is in the rhythm business.”

— “Writers Who Talk, Talkers Who Write,” essay draft, 1968

“Could there be a light so far that when/ you stop you make a shadow forever?”

— “Passing a Pile of Stones,” A Glass Face in the Rain; this, of course, is a likely candidate to become an epigraph in my book, whose working title is The Shadow Poet.

“Wherever you are, there is another door.”

— “Smoke,” Smoke’s Way

“No matter how willing and weak your own/ face is, you know another face/ for you somewhere in the world: your house.”

— “Looking for You,” Smoke’s Way

“Set free, the mind discovers shortcuts and arabesques through and over and around all purposes.”

— Writing the Australian Crawl

“Animals full of light/ walk through the forest/ toward someone aiming a gun/ loaded with darkness./ That’s the world: God/ holding still/ letting it happen again/ and again and again.”

— “Meditation,” the whole poem, frequently reprinted

“Those mad rulers at times elsewhere,/ inhuman and yet mob-worshipped,/ leaders of monstrous doctrine, unspeakable/ beyond belief, yet strangely attractive to/ the uninstructed.”

— “Help from History,” An Oregon Message]

“But some facts happen only to people who are ready/ for how the Yukon turns over when you say its name.”

— “For People with Problems About How to Believe,” An Oregon Message

“And you live beside me, millions of stars away.”

— “Where We Live,” Learning to Live in the World

“A poem is a serious joke, truth that has learned jujitsu.”

— “What It Is Like,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“The only connection we make/ is like a twinge when sometimes they change/ the beat in music, and we sprawl with it/ and hear another world for a minute/ that is almost there.”

— “Sending These Messages,” A Glass Face in the Rain

“You turn your head—/ that’s what the silence meant: you’re not alone./ The whole wide world pours down.”

–“Assurance,” Smoke’s Way

“In my life, I will more than live.”

— “Reminders,” Learning to Live in the World

“(I)ntention endangers creation.”

— Writing the Australian Crawl

“If you let your thought play, turn things this way and that, be ready for liveliness, alternatives, new views, the possibility of another world—you are in the area of poetry.”

— “What It Is Like,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“Poems don’t just happen. They are luckily or stealthily related to a readiness within ourselves.”

— Introduction, Since Feeling Is First

“I feel ready to follow even the most trivial hunch, and my notes to myself are full of beginnings, wavery hints, all kinds of inconclusive sequences sustained by nothing more than my indulgent realization that if it occurred to me it might somehow by justified.

— “A Statement on Life and Writing,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“Now and then a sequence appeals to me for long enough to be teased into something like a poem, and when I feel sufficient conviction, I detach it from the accumulated leaves—my compost heap—and halfheartedly send it around to editors.”

— “A Statement on Life and Writing,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“What one has written is not to be defended or valued, but abandoned: others must decide significance and value.”

— “Writing and Literature: Some Opinions,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“A poem today is anything said in such a way or put on the page in such a way as to invite from the hearer or reader a certain kind of attention.”

— “The End of a Golden String,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“Only the golden string knows where it is going, and the role for a writer or reader is one of following, not imposing.”

— “The End of a Golden String,” Writing the Australian Crawl

“A realization: my slogan for writing—lower your standards and go on—applies to living, to getting old.”

— Sound of the Ax

“My typical act is—hit the road.”

— Sound of the Ax